Clerical Claustrophobia Part 2

The first post of this two-part series is here.At the time I was accused and faced trial in 1994, my attorney

sought the help of my Diocese to defend the case. I was

sitting in the attorney’s office on the day he called the

Chancellor of my diocese asking for details of the protocol

for reporting accusations of abuse to state officials.The Chancellor, a monsignor, said that the diocese had never had

to make such a report until accusations emerged against me. I

was the only one, he said.

The first post of this two-part series is here.At the time I was accused and faced trial in 1994, my attorney

sought the help of my Diocese to defend the case. I was

sitting in the attorney’s office on the day he called the

Chancellor of my diocese asking for details of the protocol

for reporting accusations of abuse to state officials.The Chancellor, a monsignor, said that the diocese had never had

to make such a report until accusations emerged against me. I

was the only one, he said.

Months later as I prepared for trial, the Chancellor and a diocesan lawyer issued a press release about me. Knowing that I refused “plea deals,” maintained my innocence, and struggled to mount a defense, the press release declared:“The Church has been a victim of the actions of Gordon MacRae just as these individuals.”My trial, from that point on, was but a farce.

Eight years later, when my diocese entered into an agreement

with state officials to publish the files of all accused

priests - both those convicted of crimes and those who had

merely been accused - I learned that my attorney and I had

been lied to. I was not the only priest so accused.In fact,

some sixty-two priests of my diocese - almost half the current

number of diocesan priests - had faced accusations of sexual

abuse over a forty year period. Almost all of them were the

subjects of quiet financial settlements with no publicity, a

pattern agreed to at the time by the diocese, the claimants,

and their contingency lawyers.I do not blame my brother priests for feeling hostility, but I

am perplexed by how much it has lingered, and even supplanted

mercy and charity.I DO NOT KNOW HIMAmong my closest friends in the priesthood was a priest in my

diocese with whom I vacationed each year. We hiked in Acadia

National Park in Maine and climbed the Jemez Mountains in New

Mexico. He was a defense witness in my trial, and spoke of

his firm belief that I was falsely accused. From the moment I

was convicted and sent to prison, however, I never heard from

him again. I was in prison sixty miles from his rectory, and

he never visited, never responded to a letter. Had our places

been reversed, Lord forbid, I could not imagine leaving him

stranded in prison. I had been in prison for eight years when I saw my friend’s

face on the local television news one night. No, he had not

been accused. He was canoeing on his day off, fell from his

canoe, and suffered a fatal heart attack. It was his 60th

birthday. It is a monument to the immense destructive power

of sex abuse accusations that my spontaneous and immediate

reaction was a feeling of relief that my friend was in the

news because of his death rather than an accusation from which

he would never fully recover his good name.I was profoundly

sad by his death and by my reaction. I do not have the words

to express such sadness.Over time, I have come to see the demeanor of other priests

less in terms of myself and more in terms of what they must be

going through. What could possibly have caused my friend to

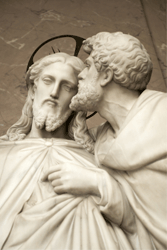

turn his back on me and on the Corporal Works of Mercy?The

fear wrought by the clerical scandal has done more harm to the

priesthood than the scandal itself. The Church is in danger of

losing far more than the $2.6 billion exacted by claims of

abuse. We are in danger of losing our most sacred trust on

Earth: our capacity for mercy.SELF-EMPLOYED PRIESTS?It had to be terribly demoralizing for priests to learn that

one bishop in a now infamous deposition referred to priests as

“independent contractors.” Another bishop declared under oath that priests are, for legal purposes, “self-employed.”Such

unfortunate defenses were, of course, attempts to reign in

vicarious liability in civil lawsuits. All corporations practice risk aversion driven by their disdain for lawsuits in the modern age. The Dallas Charter and “zero tolerance” are the work of CEO’s, not shepherds.As Charlene Duline asks in her memoir, Drinking from the Saucer, “What kind of shepherd abandons his sheep when they misstep?”Perhaps New England is still too close to the epicenter of The

Scandal for reason and hope to yet fully replace blaming and

fear. I hear from many priests from throughout the U.S. who

are appalled at the attitude of scapegoating that has thus far

prevailed here. Many are men in religious orders who find it

simply inconceivable that a priest can be discarded and

shunned because of a decades-old unproven claim.

I had been in prison for eight years when I saw my friend’s

face on the local television news one night. No, he had not

been accused. He was canoeing on his day off, fell from his

canoe, and suffered a fatal heart attack. It was his 60th

birthday. It is a monument to the immense destructive power

of sex abuse accusations that my spontaneous and immediate

reaction was a feeling of relief that my friend was in the

news because of his death rather than an accusation from which

he would never fully recover his good name.I was profoundly

sad by his death and by my reaction. I do not have the words

to express such sadness.Over time, I have come to see the demeanor of other priests

less in terms of myself and more in terms of what they must be

going through. What could possibly have caused my friend to

turn his back on me and on the Corporal Works of Mercy?The

fear wrought by the clerical scandal has done more harm to the

priesthood than the scandal itself. The Church is in danger of

losing far more than the $2.6 billion exacted by claims of

abuse. We are in danger of losing our most sacred trust on

Earth: our capacity for mercy.SELF-EMPLOYED PRIESTS?It had to be terribly demoralizing for priests to learn that

one bishop in a now infamous deposition referred to priests as

“independent contractors.” Another bishop declared under oath that priests are, for legal purposes, “self-employed.”Such

unfortunate defenses were, of course, attempts to reign in

vicarious liability in civil lawsuits. All corporations practice risk aversion driven by their disdain for lawsuits in the modern age. The Dallas Charter and “zero tolerance” are the work of CEO’s, not shepherds.As Charlene Duline asks in her memoir, Drinking from the Saucer, “What kind of shepherd abandons his sheep when they misstep?”Perhaps New England is still too close to the epicenter of The

Scandal for reason and hope to yet fully replace blaming and

fear. I hear from many priests from throughout the U.S. who

are appalled at the attitude of scapegoating that has thus far

prevailed here. Many are men in religious orders who find it

simply inconceivable that a priest can be discarded and

shunned because of a decades-old unproven claim.

I believe, as Cardinal Dulles wrote to me in 2005:“The time is bound to come when the tide will shift, and even the bishops [and priests] will be ready to hear the [accused] priests’ side of the story. The change will come, but not before the public is prepared for it by [stories] such as yours.”

I believe we are coming to a crossroad under this burden of scandal. Clericalism and the clerical culture within the Church are giving way to what Father John Zuhlsdorf called “the sacred priesthood of service.” In this, we are collaborators with the laity in a Great Mission, to lead souls to Christ, and we must not lose sight of it.I find much hope in the emergence of sites like “Priests in Crisis” and “These Stone Walls,” both propagated and launched through the singular courage of lay members of the Church.Perhaps it is time for us priests to lean on them and to learn from them. As John Henry Cardinal Newman once pointed out, we clergy would look pretty silly without them.