In God We Trust: Living with the Author of Life

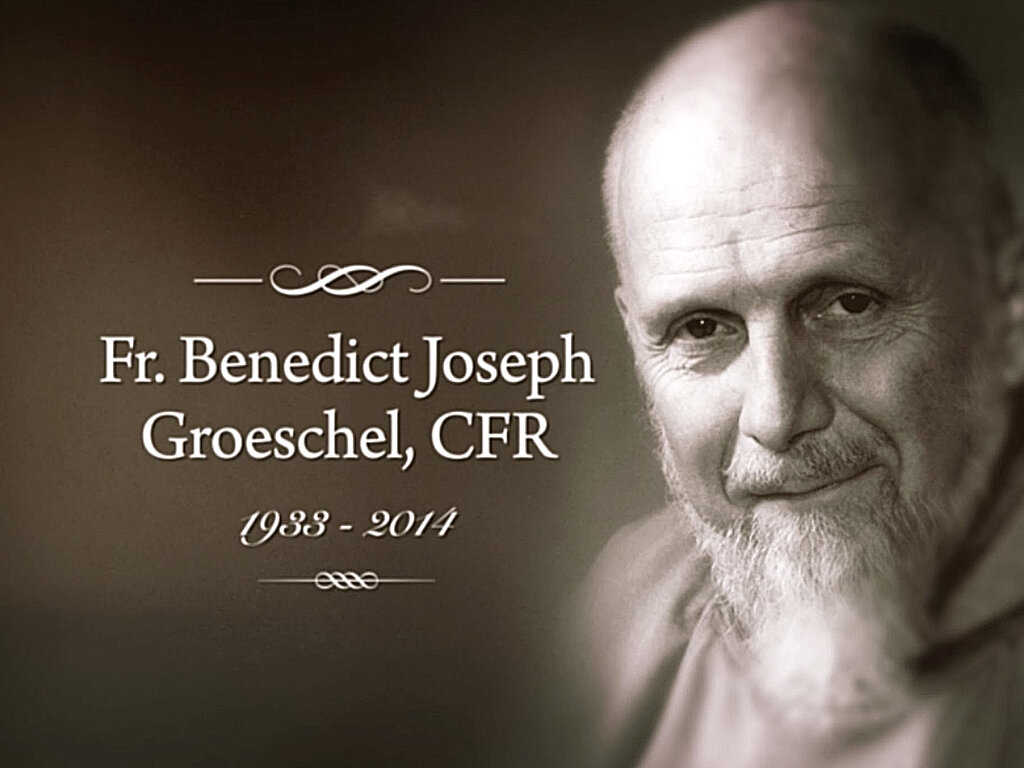

Seeing God in suffering in a world in semi-darkness is a great spiritual challenge of our age. Father Benedict Groeschel lived in cooperation with Divine Providence.

Seeing God in suffering in a world in semi-darkness is a great spiritual challenge of our age. Father Benedict Groeschel lived in cooperation with Divine Providence.

“One preparing to sail and about to voyage over raging waves calls upon a piece of wood more fragile than the ship which carries him. For it was desire for gain that planned that vessel, and wisdom was the craftsman who built it, but it is Thy Providence, O Father, that steers its course giving it a path in the sea, and safe passage through the waves.” (Wisdom of Solomon 14:1-3)

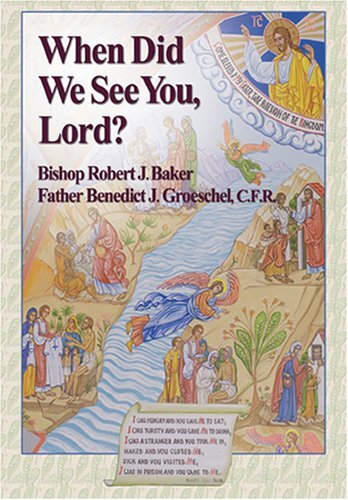

When I wrote “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night,” I typed it from my heart without notes or drafts in a single sitting as I usually do. It wasn’t until I got to the end of it that I realized it needed a Part Two, posted last week as “Saint Maximilian Kolbe: A Knight at My Own Armageddon.” But before I even began that Part Two, I learned that there also must be a Part Three, and this is it.This Part Three became necessary to tell you about a strange thing that happened on the afternoon of Wednesday August 3, the same day my post about Father Benedict Groeschel was published on These Stone Walls. I was at work in the prison library where I have worked for the last ten years. Someone dropped a trash bag full of books next to my desk. They were books that returned from various locations around the prison from prisoners in maximum security or other places who cannot personally come to the library.I had to check all the books back into the library system and examine them for damage before putting them on a cart to be reshelved, then checking out new ones to send back to the men in “the hole.” This library has about 22,000 volumes with 1,000 books checked in or out every week so the bag of books was nothing unusual.But when I reached into the bag for a handful of books, the first one I looked at brought a jolt of irony. It was a little hardcover book I had never seen before. The book had once been in the library system, but was stamped “discarded” in 2005 which was about a year before I went to work there. For over ten years the book traveled from place to place in this prison, finally ending up in a bag at my desk on that particular day. When I looked at the book’s cover, I was stricken with the bizarre irony of it. On the same day we published “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night,” I was holding in my hand a little book titled, When Did We See You, Lord by Bishop Robert Baker and Father Benedict J. Groeschel published by Our Sunday Visitor in 2005.I know that Father Groeschel has written many hooks, but I had never before seen one in this prison library. The “coincidence” of it showing up on that particular day wasn’t the only irony. The book is a series of meditations on Matthew 25:31-46, the Biblical source for the Corporal Works of Mercy. The book’s last chapter is titled “For I was in prison and you came to me.”And if that still wasn’t irony enough, when I turned to the book’s preface, I read that it is based on a series of retreat talks given by Father Groeschel in 2002 to the bishop, priests and deacons of the Diocese of Manchester New Hampshire - my diocese - while I was in prison twenty miles away.This is the one small thing that God and I have in common. We both really appreciate irony. I use it a lot when I write, and so does He. But in His hands it is a work of art. In the wonderful preface to this little book, Catholic writer and editor, the late Michael Dubruiel wrote:

When I looked at the book’s cover, I was stricken with the bizarre irony of it. On the same day we published “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night,” I was holding in my hand a little book titled, When Did We See You, Lord by Bishop Robert Baker and Father Benedict J. Groeschel published by Our Sunday Visitor in 2005.I know that Father Groeschel has written many hooks, but I had never before seen one in this prison library. The “coincidence” of it showing up on that particular day wasn’t the only irony. The book is a series of meditations on Matthew 25:31-46, the Biblical source for the Corporal Works of Mercy. The book’s last chapter is titled “For I was in prison and you came to me.”And if that still wasn’t irony enough, when I turned to the book’s preface, I read that it is based on a series of retreat talks given by Father Groeschel in 2002 to the bishop, priests and deacons of the Diocese of Manchester New Hampshire - my diocese - while I was in prison twenty miles away.This is the one small thing that God and I have in common. We both really appreciate irony. I use it a lot when I write, and so does He. But in His hands it is a work of art. In the wonderful preface to this little book, Catholic writer and editor, the late Michael Dubruiel wrote:

“Sometimes, ironically, life imitates art: as this book was being written, Father Benedict was involved in a horrific accident that nearly took his life. At the time of the accident, the text he was working on was in his suitcase - the just finished Introduction to ‘For I was a stranger and you welcomed me,’ [Chapter 3 of When Did We See You Lord?].”

HOPELESSNESS AND SUICIDEIn the introduction to his chapter entitled, “When I was in prison, you came to me,” Father Groeschel told a story very familiar to me. I knew him well forty years ago when he and I were both members of the Capuchin Province of Saint Mary where I began my priesthood formation. Father Groeschel was the homilist for my first profession of vows which (another irony!) took place forty years ago this very day, August 17, 1976.At the time, Father Benedict was chaplain of a facility for delinquent young men in upstate New York. Some of those young men later landed in prison so Father Groeschel was a frequent visitor to prisons throughout New York State. One day he went to one of them to visit a young prisoner he knew, but he arrived at an inconvenient time. All the prisoners were locked down for the daily count.While he waited, one of the guards who knew him invited Father Groeschel to a prison lunch which he described as “nothing fancy, a bowl of starchy soup and some bread.” While he was eating, the guard came back and asked Father Groeschel to follow him quickly. A young prisoner had just hanged himself.Father Groeschel and the guard went running up the stairs to the end of a cellblock. There on the floor was the lifeless body of a young man surrounded by guards and a prison doctor performing CPR. When the young prisoner regained consciousness, Father Groeschel bent over him and started to talk to him:

“He looked at me with this very beautiful smile - like he knew me, like he expected me to call him by name - and at first I couldn’t figure that out since I had never seen this boy before. Then I realized the boy thought he was dead. He had just hanged himself, and he opened his eyes to see this figure in a long robe and beard, and thought I was Someone else. I was horrified, so I moved my head so he could see the guards and ceiling of the cellblock. When I did so, he began to cry bitter tears, the bitterest tears I have ever seen... I was not the One he thought I was, but I was mistaken too. I thought he was just a prisoner when, indeed, he was the disguised Son of God.” (p. 153)

I was involved with a similar near tragedy in prison. It was in 2003, exactly ten years after the events I wrote about in my August 3 post. It was not so overcrowded in this prison then. Bunks and prisoners did not fill the recreation areas outside our cells as they do today. One day in 2003 at about this time of year, late on a weekday morning, most of the prisoners from this cellblock had gone to lunch. I was reading a newspaper, enjoying the rare twenty minutes of quiet at a table outside my cell. In the distance, my mind registered a barely audible metallic click.Over time in this place, every mechanical sound comes to have meaning, even sounds that register just below the level of consciousness. The clink of keys when a guard is approaching, the vague static sound the PA system makes just before a name is called, the electronic buzz of distant prison doors opening and closing. They all register just below the psyche.That distant metallic click I heard that day also registered. It was the sound of a cell door locking, but the cell doors in this medium security prison are not locked during the day. I sat there alone with my newspaper, then suddenly looked up. My eyes scanned both tiers of cells in this cellblock. All the doors were ajar except one, cell number six near the end of the row of cells where I live.Not many prisoners would freely lock themselves in a cell midday, so I closed my paper and walked down the tier to that cell door. Through the narrow window in the locked door, I saw a young man standing on the upper bunk. He had taken a cord from somewhere and fed one end of it through the cell’s ceiling vent. He had tied the other end around his neck, and just as I got to the door, he jumped I watched in horror as he dangled, swinging and choking from the vent. There was no way I could get in that locked door and there was no one around. I shouted repeatedly at him to step back, onto the bunk.Our eyes met, and what I saw was utter hopelessness. As the life was slowly choking out of him, nothing that I shouted made a difference. The seconds seemed eternal, but finally the first prisoner returning from lunch was buzzed through the cellblock door in the distance. Just before it closed behind him I yelled with all my might for him to get back out there and get the door to cell six open. The guy later said that I scared the hell out of him. He went to the control room and asked a guard to open cell six, which he did by pressing an electronic switch.Finally, I heard the loud pop of the door’s lock disengaging and I swung the door open. The dangling prisoner was still. I rushed in and lifted him up while the other man ran to getsome help. Two guards came in and cut the young man down. We got the cord from around his neck and laid him on the cell floor. His breathing was labored, and the cord had left a deep gash around his neck that never fully disappeared. While he was being escorted out of the cell by the guards, he cursed at me. He choked out the bitter words, but they were clear enough for me to understand. It was his version of bitter tears, and like those witnessed by Father Groeschel, they were the bitterest tears I have ever seen.Once he was cleared from the Medical Unit, the young man was sent to the prison’s Secure Psychiatric Unit for a time. I saw him a few times after that when the prisoners there were permitted to come to the library. He always avoided eye contact with me, then one day I decided to broach the topic directly. “I’m not sure where you are with what happened,” I said, “but I do not regret what I did.” “Why did you stop me” he asked. I responded with as much kindness as I could summon:

“Because I once stood where you stand now, and have learned that we are the stewards, not the masters, of the life God has given us. What would it say about me if I ignored the Divine Providence of the Author of Life?”

LIVING WITH THE AUTHOR OF LIFEHe looked at me thoughtfully for a few moments, then asked what I meant by “Divine Providence.” I explained that there were many unusual factors that all had to be in place for me to be where I was at that very moment to hear his door click. One of them was that I was having a really bad day and needed twenty minutes of quiet so I skipped lunch. “That’s what I mean by Divine Providence.” He considered this, nodded, then left with the bare hint of a smile. It dawned on me only well after he left that one of the steps Divine Providence had to have in place that day was the necessity of my surviving my own suicide attempt a decade earlier.During Lent last year, I wrote a post entitled, “Forty Days of Lent Without the Noonday Devil.” It featured a really terrific and monumentally helpful book by Catholic psychiatrist, Aaron Kheriaty, M.D. entitled, The Catholic Guide to Depression (Sophia Institute Press 2012). The book’s intriguing subtitle is “How the Saints, the Sacraments, and Psychiatry Can Help You Break Its Grip and Find Happiness Again.”Dr. Kheriaty wrote something that I have come to know without doubt from personal experience. He wrote that in multiple studies in psychiatry, the one factor that Christianity, and especially Catholicism, lends to the prevention of suicide is the theological virtue of hope:

“The one factor most predictive of suicide was not how, sick a person was, or how many symptoms he exhibited, or how much pain he or she was in. The most dangerous factor was a person’s sense of hopelessness. The patients who believed their situation was utterly without hope were the most likely candidates for completing suicide. There is no prescription or medical procedure for instilling hope. This is the domain of the revelation of God ... the only hope that can sustain us is supernatural - the theological virtue of hope which can be infused only by God’s grace.” (pp. 98-99)

As an example of this virtue of hope, Dr. Kheriaty goes on to describe a practice that is at its essence. It’s a practice that I learned from Saint Maximilian Kolbe who is here with me, and I today practice it to the best of my ability on a daily basis. Dr. Kheriaty writes that it “unites us in a deeper way to Jesus Christ, allowing us to participate in his redemptive mission.” It is what Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI described in his Magisterial encyclical, Spe Salvi - Salvation and Hope - as suffering in union with Christ on the Cross:

“What does it mean to offer something up? Those who did so were convinced that they could insert these little [or big] annoyances into Christ’s great compassion so that they somehow became part of the treasury of compassion so greatly needed by the human race.” (Spe Salvi, no. 40)

It is from this treasury of compassion that the readers of These Stone Walls have offered prayers for me, that I may experience justice. You have met in a powerful way that urgent summons from the Gospel and Father Benedict Groeschel: “When I was in prison, you came to me.” You have brought hope to our prison door, and I thank you. I offer these days of unjust confinement for you. When a reader asks for my prayers in a comment or a letter, I choose a specific day in prison to offer for that person. I get the better end of the deal. Hope is precious, and fragile, and sometimes spread thin.Father Benedict Groeschel gets the last word:

“On January 11, 2004, I was struck by a car and brought to the absolute edge of death. There is no real reason why I am alive, and there is no earthly reason why I am able to think and speak. I had no vital signs for 27 minutes, and no blood pressure. It’s amazing that not only did I survive but that I still have the use of mental equipment, which begins to deteriorate in three or four minutes without a blood supply... 50,000 people wrote e-mails promising prayers.” (When Did We See You, Lord? pp. 123-124)“For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God.” (Colossians 3:3)