The Catholic League, Saint Patrick and the Labyrinthine Ways

The Catholic League honors Saint Patrick today, the Apostle of Ireland whose life is an enigma of sorrow and grace - just like ours.The March issue of Catalyst, the Journal of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, has an editorial entitled "These Stone Walls." Catholic League President Bill Donohue encouraged members to visit TSW for its "wealth of information on Catholic issues" as well as material on my "ordeal." There are not too many things that leave me speechless these days, but this was one of them.If you're not a Catholic League member, I highly recommend becoming one. A monthly subscription to Catalyst certainly woke me up to the reality of anti-Catholic prejudice in our culture, and to a growing effort to remove a Catholic voice and Catholic influence and values from the public square. Bill Donohue's eye-opening book, Secular Sabotage, (FaithWords, 2009) left me with no doubt that he and The Catholic League are on the front line of the culture war for the preservation of what we believe as Catholics in an increasingly hostile culture.

The Catholic League honors Saint Patrick today, the Apostle of Ireland whose life is an enigma of sorrow and grace - just like ours.The March issue of Catalyst, the Journal of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, has an editorial entitled "These Stone Walls." Catholic League President Bill Donohue encouraged members to visit TSW for its "wealth of information on Catholic issues" as well as material on my "ordeal." There are not too many things that leave me speechless these days, but this was one of them.If you're not a Catholic League member, I highly recommend becoming one. A monthly subscription to Catalyst certainly woke me up to the reality of anti-Catholic prejudice in our culture, and to a growing effort to remove a Catholic voice and Catholic influence and values from the public square. Bill Donohue's eye-opening book, Secular Sabotage, (FaithWords, 2009) left me with no doubt that he and The Catholic League are on the front line of the culture war for the preservation of what we believe as Catholics in an increasingly hostile culture. I have written two articles for Catalyst on the sex abuse crisis in the Church: "Sex Abuse and Signs of Fraud" (Nov. 2005) and "Due Process for Accused Priests" (Jul/Aug. 2009). It took a degree of courage for Bill Donohue to publish these, and to so openly recommend These Stone Walls. The amount of money that has changed hands in the aftermath of the U.S. Catholic sex abuse crisis is approaching $3 billion. There are many people highly invested in keeping that momentum going, and in silencing any attempt to rein it in with some truth. I know The Catholic League took some heat for publishing the point of view of a falsely accused priest. You would do me a service by clicking on the feedback link on The Catholic League website to commend this organization for its stand.HOW THE IRISH SAVED CIVILIZATIONThese Stone Walls shared the March issue of Catalyst with its annual "St. Patrick's Day Alert" inviting subscribers to join The Catholic League in New York's celebrated annual march up Fifth Avenue today to honor "The Apostle of Ireland.” The Catholic League's announcement reminded me of how very big a deal Saint Patrick's Day is in New York, Boston, and many other American cities.

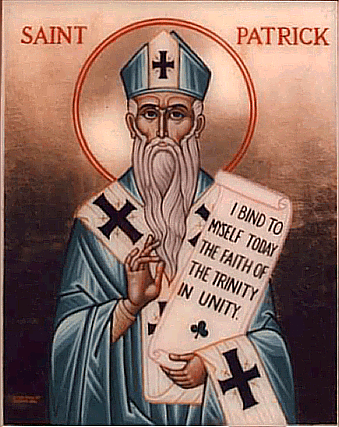

I have written two articles for Catalyst on the sex abuse crisis in the Church: "Sex Abuse and Signs of Fraud" (Nov. 2005) and "Due Process for Accused Priests" (Jul/Aug. 2009). It took a degree of courage for Bill Donohue to publish these, and to so openly recommend These Stone Walls. The amount of money that has changed hands in the aftermath of the U.S. Catholic sex abuse crisis is approaching $3 billion. There are many people highly invested in keeping that momentum going, and in silencing any attempt to rein it in with some truth. I know The Catholic League took some heat for publishing the point of view of a falsely accused priest. You would do me a service by clicking on the feedback link on The Catholic League website to commend this organization for its stand.HOW THE IRISH SAVED CIVILIZATIONThese Stone Walls shared the March issue of Catalyst with its annual "St. Patrick's Day Alert" inviting subscribers to join The Catholic League in New York's celebrated annual march up Fifth Avenue today to honor "The Apostle of Ireland.” The Catholic League's announcement reminded me of how very big a deal Saint Patrick's Day is in New York, Boston, and many other American cities. Saint Patrick's Day not only celebrates the Saint himself, but the impact the Irish have had in both American culture and world affairs. Author and historian Thomas Cahill devoted one of the seven volumes of his acclaimed "Hinges of History" series to How the Irish Saved Civilization (Anchor Books, 1996). It will make you proud to have even a twinge of Irish in you.I actually started a post for today that had nothing to do with Saint Patrick, but he kept calling to me from ancient shores. My mother was Irish by way of Newfoundland (see "A Corner of the Veil"). I just didn't feel I could get away without a mention of Patrick and his conversion of Ireland. I kept seeing my mother's face with "that look," and I knew that resistance was futile.The story of how the Irish saved civilization began with Saint Patrick of Ireland, but he's one of history's mysteries. For such an iconic figure in both pop culture and religious history we know precious little about him. Patrick is popularly proclaimed "the Apostle of Ireland," but he wasn't even Irish. His birthplace was somewhere in Roman occupied England, likely in the southwest. Late in the fourth century, Patrick's own writings identified his birthplace as a Roman town called Bannavem Taberniae. No one has a clue where it was. His father's name was Calpurnius, clearly a Roman name.Like many heroes of faith, Patrick was not religious at all early on. His conversion came in young adulthood when he met with disaster. Sometimes people find faith only when they most desperately need it. At age sixteen, around the year 405, Patrick was kidnapped by Irish raiders - along with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of others - and taken to Ireland where he was forced into slavery as a shepherd. There's a bit of prophetic irony in that fact, but it shouldn't be treated lightly as history is sometimes inclined to do. The teenager Patrick was forced from his home, his family, his traditions, and his future as it was to be. He was dragged off into indentured servitude. It had to be devastating.Six years later, Patrick escaped his suffering at the hands of the Irish, and made his way to the northern coast of Gaul to what is now Belgium or France. There, Patrick studied in some unknown location, and was ordained a priest.Then, for some bizarre reason, Patrick returned to the place of his captivity. He did this, according to his brief writings, because of a dream in which a man named Victoricus ("The Victor") came to him from Ireland. In the dream, Victoricus handed Patrick a letter that began with the words, "The voice of the Irish," and concluded, "We ask thee, boy, come and walk among us once more." That's Patrick's only explanation for whatever drew him back across the Irish Sea to the place where he was forced into servitude.

Saint Patrick's Day not only celebrates the Saint himself, but the impact the Irish have had in both American culture and world affairs. Author and historian Thomas Cahill devoted one of the seven volumes of his acclaimed "Hinges of History" series to How the Irish Saved Civilization (Anchor Books, 1996). It will make you proud to have even a twinge of Irish in you.I actually started a post for today that had nothing to do with Saint Patrick, but he kept calling to me from ancient shores. My mother was Irish by way of Newfoundland (see "A Corner of the Veil"). I just didn't feel I could get away without a mention of Patrick and his conversion of Ireland. I kept seeing my mother's face with "that look," and I knew that resistance was futile.The story of how the Irish saved civilization began with Saint Patrick of Ireland, but he's one of history's mysteries. For such an iconic figure in both pop culture and religious history we know precious little about him. Patrick is popularly proclaimed "the Apostle of Ireland," but he wasn't even Irish. His birthplace was somewhere in Roman occupied England, likely in the southwest. Late in the fourth century, Patrick's own writings identified his birthplace as a Roman town called Bannavem Taberniae. No one has a clue where it was. His father's name was Calpurnius, clearly a Roman name.Like many heroes of faith, Patrick was not religious at all early on. His conversion came in young adulthood when he met with disaster. Sometimes people find faith only when they most desperately need it. At age sixteen, around the year 405, Patrick was kidnapped by Irish raiders - along with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of others - and taken to Ireland where he was forced into slavery as a shepherd. There's a bit of prophetic irony in that fact, but it shouldn't be treated lightly as history is sometimes inclined to do. The teenager Patrick was forced from his home, his family, his traditions, and his future as it was to be. He was dragged off into indentured servitude. It had to be devastating.Six years later, Patrick escaped his suffering at the hands of the Irish, and made his way to the northern coast of Gaul to what is now Belgium or France. There, Patrick studied in some unknown location, and was ordained a priest.Then, for some bizarre reason, Patrick returned to the place of his captivity. He did this, according to his brief writings, because of a dream in which a man named Victoricus ("The Victor") came to him from Ireland. In the dream, Victoricus handed Patrick a letter that began with the words, "The voice of the Irish," and concluded, "We ask thee, boy, come and walk among us once more." That's Patrick's only explanation for whatever drew him back across the Irish Sea to the place where he was forced into servitude.

Patrick was not the most scholarly of priests. His Latin was blunt and rough, and did not reflect the typical education of a European priest, even then. He identified himself as "the least educated" of priests, and his writings reflect that fact. What Patrick brought into his life as a priest was his experience of tragedy and trial. Armed with those, sometime around 431, Patrick was named the second Bishop of Ireland, and served until his death in or around 461. In between, he unified and converted an entire nation to Christ.

The Irish term "seamrog" - pronounced "shamrock" and meaning "little clover" - is the national symbol of Ireland. You will likely see it everywhere today. It's also a symbol of "good luck" throughout western culture, and for only one reason. Patrick was said to have once plucked it from the ground to illustrate the doctrine of the Trinity to a people who knew nothing of faith, and knew only the earth. The theological insight using the simple plant with three distinct leaves in near perfect symmetry was not a symbol Patrick learned in higher education. He learned it as a shepherd, down on the ground in captivity, and it was a sort of personal revelation. It made perfect sense to him in a time and place in which all sense had been robbed and distorted by his loss of freedom.

Ireland was the only country in western Europe whose conversion required no martyrs. Patrick was a "white and green" martyr, a designation devised by an Irish priest in one of the earliest sermons to survive in the ancient tongue:

"Is i ban-martra do dhuine, an tan, scaras, ar son De, re gach rud a charas.""This is white martyrdom to a man, when he renounces everything he loves for God; this is green martyrdom to a man, when by fasting and labour he does penance."(The Course of Irish History, T.W. Moody and F.X. Martin Roberts Rinehart 1995, p. 63).

PILLARS OF THE EARTHReligious history is filled with heroes whose early journeys took a path of suffering, sorrow, or sin. Can the Book of Genesis tell its tale without Adam's and Cain's expulsion To the Land of Nod, East of Eden? Can salvation history unfold without the story of Joseph sold into slavery by his own brothers? Can Exodus make sense without Moses abandoned at birth, without the Jews in captivity, without the Destroying Angel and the Passover? Could any of the Old Covenant be fulfilled without the tragedy of the New Covenant, without John the Baptist's head on a platter, without Christ betrayed, without the Scandal of the Cross?We are a faith built upon great paradox, but the paradox we often overlook as faith-full is the one we are living. It's a paradox of faith that all the men and women we revere in faith history were forged into the icons we know as saints - like Saint Patrick - because of someone's sin, or suffering, or sorrow. If we honor their halos without also honoring their shadows, we acknowledge only half of the crucible in which their sanctity was forged. Be careful, because going down this path might mean seeing our own sins, and sorrows, and struggles in another light, through another set of glasses.Ten years ago in prison, I read a historical novel by British Author, Ken Follett entitled Pillars of the Earth (William Morrow & Co. 1989). I liked it immensely, and recommended it to many others in and outside of  prison. It's not a very reverent book. Some of it will make you wince, as it did me. Some of its heroes are priests and at least one memorable villain is a bishop. (And no, that's not why I liked it!). Its 973 pages make it a challenging tome, and the subject matter didn't interest me at all at first. I'm not sure now what made me pick it up, but I did, and then I could not put it down. I read it twice.Pillars of the Earth is Ken Follett's masterpiece. He wrote it because of his great awe at the construction and majesty of England's Gothic cathedrals and the era in which they arose from the artistry of man's inspiration. Pillars of the Earth follows the life of a family of stone masons through two generations in 12th century England. Ken Follett conducted tireless research to capture the tools, the people, their values, and the challenges of the time, and the result is brilliant and memorable. The Church Triumphant - the Church of faith - is at the very heart of the story, while the all-too-human Church of this world is worn as a millstone around the necks of believers. Pillars of the Earth has the paradox in the life of the Church reflecting both grace and shadow - just like the lives of its members.THE LABYRINTHINE WAYSThe real lure of Pillars of the Earth, however, is a lesson taught to its readers in ways subtle and profound. The characters live a linear existence - just like us - and are entirely unaware of the ways their lives, and choices, and actions impact others in a ripple effect. The reader is thrust into the position of seeing the book from above, almost as an observer at God's side. There is a bigger picture unfolding for the reader, and it is marvelous to behold. I wonder if Ken Follett really intended it, but the central character in the story is the one who is never named: the labyrinthine ways of grace.I hear from many people who suffer as a consequence of sin - their own or someone else's - and are mired deeply in its grip awaiting deliverance, decision, direction. Some struggle with vocation, others with captivity, others with personal tragedy, and everyone struggles with the past. We're trapped in the circumstances in which we live, and we cannot see the bigger picture. Neither could Rabbi Jachanan walking with the Prophet Elijah in Merlin's tale in "Descent into Lent."The part of St. Patrick's story about being carried off by marauders and forced into six years of slavery is seen through the eyes of Irish history as part of the "lucky charm" of St. Patrick's life. Think about that! I doubt very much that it felt that way at age sixteen. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time - or the right place at the right time depending on your point of view.Would Patrick be Saint Patrick without that awful six years of his life? I doubt it. We're in an unholy quagmire if we're hell-bent on shedding where we are in life, or where we've been. God's pursuit of us calls not just our halo, but our shadow as well. We can leave neither behind, and there's no point in running. Just as with "that look" my Irish mother mastered, resistance is futile.

prison. It's not a very reverent book. Some of it will make you wince, as it did me. Some of its heroes are priests and at least one memorable villain is a bishop. (And no, that's not why I liked it!). Its 973 pages make it a challenging tome, and the subject matter didn't interest me at all at first. I'm not sure now what made me pick it up, but I did, and then I could not put it down. I read it twice.Pillars of the Earth is Ken Follett's masterpiece. He wrote it because of his great awe at the construction and majesty of England's Gothic cathedrals and the era in which they arose from the artistry of man's inspiration. Pillars of the Earth follows the life of a family of stone masons through two generations in 12th century England. Ken Follett conducted tireless research to capture the tools, the people, their values, and the challenges of the time, and the result is brilliant and memorable. The Church Triumphant - the Church of faith - is at the very heart of the story, while the all-too-human Church of this world is worn as a millstone around the necks of believers. Pillars of the Earth has the paradox in the life of the Church reflecting both grace and shadow - just like the lives of its members.THE LABYRINTHINE WAYSThe real lure of Pillars of the Earth, however, is a lesson taught to its readers in ways subtle and profound. The characters live a linear existence - just like us - and are entirely unaware of the ways their lives, and choices, and actions impact others in a ripple effect. The reader is thrust into the position of seeing the book from above, almost as an observer at God's side. There is a bigger picture unfolding for the reader, and it is marvelous to behold. I wonder if Ken Follett really intended it, but the central character in the story is the one who is never named: the labyrinthine ways of grace.I hear from many people who suffer as a consequence of sin - their own or someone else's - and are mired deeply in its grip awaiting deliverance, decision, direction. Some struggle with vocation, others with captivity, others with personal tragedy, and everyone struggles with the past. We're trapped in the circumstances in which we live, and we cannot see the bigger picture. Neither could Rabbi Jachanan walking with the Prophet Elijah in Merlin's tale in "Descent into Lent."The part of St. Patrick's story about being carried off by marauders and forced into six years of slavery is seen through the eyes of Irish history as part of the "lucky charm" of St. Patrick's life. Think about that! I doubt very much that it felt that way at age sixteen. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time - or the right place at the right time depending on your point of view.Would Patrick be Saint Patrick without that awful six years of his life? I doubt it. We're in an unholy quagmire if we're hell-bent on shedding where we are in life, or where we've been. God's pursuit of us calls not just our halo, but our shadow as well. We can leave neither behind, and there's no point in running. Just as with "that look" my Irish mother mastered, resistance is futile.

“I fled Him, down the nightand down the days;I fled Him, down the archesof the years;I fled Him, down thelabyrinthine waysOf my own mind; And in themidst of tearsI hid from Him, and underrunning laughter.Up vistaed hopes I sped; and shot,precipitated,Adown Titanic glooms ofchasmed fears,From those strong feet thatfollowed, …followed, …followed after.”“ The Hound of Heaven” (excerpt) by Francis Thompson