The Paradox of Suffering: An Invitation from Saint Maximilian Kolbe

St. Maximilian Kolbe solved the paradox of suffering by offering his own life as a share in the suffering of Christ. This post is an invitation to that great adventure.A few weeks ago, after posting "The Exile of Father F. Dominic Menna," I received a message from an Oregon man who described himself as "just another one of your dumbstruck readers." Hmmm!! I had to think about that a bit before I decided to take it as a compliment. The gist of his message, however, was about the nature of suffering. The Oregon reader wondered how he would respond to suffering. He wondered whether he would still be a person of faith if he was called upon to suffer great loss, or injustice, or hardship.Of course, I hope and pray our readers never have to find out the answer to that question, but no one on this planet is entirely spared from ever suffering. The Oregon reader gave me an idea. I invite you to consider joining me in a spiritual adventure launched by Saint Maximilian Kolbe. It's the great adventure of living one's life triumphantly with Christ by offering suffering as a source of grace.Father Maximilian Kolbe founded the Militia of the Immaculata (MI) movement in 1917. On April 28th – the date of Father Maximilian’s ordination to priesthood – I posted “In Honor of Saint Maximilian Kolbe.” In that post, I wrote:

St. Maximilian Kolbe solved the paradox of suffering by offering his own life as a share in the suffering of Christ. This post is an invitation to that great adventure.A few weeks ago, after posting "The Exile of Father F. Dominic Menna," I received a message from an Oregon man who described himself as "just another one of your dumbstruck readers." Hmmm!! I had to think about that a bit before I decided to take it as a compliment. The gist of his message, however, was about the nature of suffering. The Oregon reader wondered how he would respond to suffering. He wondered whether he would still be a person of faith if he was called upon to suffer great loss, or injustice, or hardship.Of course, I hope and pray our readers never have to find out the answer to that question, but no one on this planet is entirely spared from ever suffering. The Oregon reader gave me an idea. I invite you to consider joining me in a spiritual adventure launched by Saint Maximilian Kolbe. It's the great adventure of living one's life triumphantly with Christ by offering suffering as a source of grace.Father Maximilian Kolbe founded the Militia of the Immaculata (MI) movement in 1917. On April 28th – the date of Father Maximilian’s ordination to priesthood – I posted “In Honor of Saint Maximilian Kolbe.” In that post, I wrote:

"Ninety-two years ago today ... Father Maximilian Kolbe was ordained a priest at the Collegio Serafico in Rome. On the next day, April 29, the man whose priesthood would require his life celebrated his First Mass at the "Altar of Miracles" in Rome's Basilica of Saint Andrea delle Fratte. The young Maximilian had read that at this very altar, the Blessed Mother appeared to Alphonse Ratisbonne, an event that caused his instant conversion.It was reading of this conversion that gave Maximilian the idea of evangelization through Mary's intercession. By his fifth anniversary of ordination, Pope Pius XI officially recognized Father Maximilian's Militia as a Primary Union of the Faithful."

After the Nazi invasion of Poland, Father Kolbe's MI movement cost him his freedom, and then his life. I plan to write much more of this before his August 14th Feast Day in two weeks.Today, some four million people around the globe share in saint Maximilian's apostolate of evangelization through their Consecration as living witnesses to Christ. After a nine-day period of prayer and reflection, MI members are asked to make their Consecration on one of the Church's Marian Feast Days. In two weeks, on the day after Saint Maximilian's Feast Day the day of his 1941 execution at Auschwitz - the Church celebrates the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary. It falls on a Sunday this year. That night, at Mass in our cell, my friend Pornchai Moontri, whose conversion took place on Divine Mercy Sunday this year, plans to make his Consecration to Christ through Mary as a member of the MI. At that time, I will also renew my own MI membership. The process is simple, and is explained in detail at the website for the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe (www.marytown.com.)I would like to invite as many TSW readers as possible to join us in Consecration to Christ through Mary by becoming members of the MI on August 15th. The above website provides the instructions for registering your Consecration, and for the nine-day preparation which would begin August 7th.KNIGHTS AT THE FOOT OF THE CROSSI have a further invitation. In 1983, the MI formalized the apostolate of the Knights at the Foot of the Cross. On May 31, 1983 – the Feast of the Visitation – 16 aged and infirm members of the Conventual Franciscan order – Saint Maximilian’s own order of friars – consecrated their suffering in a special apostolate within the MI. It was an apostolate of redemptive suffering. This concept grew into the Knights at the Foot of the Cross, a personal Consecration to offer our own suffering as a share in the suffering of Christ. It is offered in the spirit of Saint Maximilian Kolbe who sacrificed his life for another.

In two weeks, on the day after Saint Maximilian's Feast Day the day of his 1941 execution at Auschwitz - the Church celebrates the Solemnity of the Assumption of Mary. It falls on a Sunday this year. That night, at Mass in our cell, my friend Pornchai Moontri, whose conversion took place on Divine Mercy Sunday this year, plans to make his Consecration to Christ through Mary as a member of the MI. At that time, I will also renew my own MI membership. The process is simple, and is explained in detail at the website for the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe (www.marytown.com.)I would like to invite as many TSW readers as possible to join us in Consecration to Christ through Mary by becoming members of the MI on August 15th. The above website provides the instructions for registering your Consecration, and for the nine-day preparation which would begin August 7th.KNIGHTS AT THE FOOT OF THE CROSSI have a further invitation. In 1983, the MI formalized the apostolate of the Knights at the Foot of the Cross. On May 31, 1983 – the Feast of the Visitation – 16 aged and infirm members of the Conventual Franciscan order – Saint Maximilian’s own order of friars – consecrated their suffering in a special apostolate within the MI. It was an apostolate of redemptive suffering. This concept grew into the Knights at the Foot of the Cross, a personal Consecration to offer our own suffering as a share in the suffering of Christ. It is offered in the spirit of Saint Maximilian Kolbe who sacrificed his life for another. Pornchai and I plan to also Consecrate ourselves as Knights at the Foot of the Cross at Mass on August 15th. I learned from both patrons of These Stone Walls - Saint Maximilian and Saint Pio - that personal suffering offered for others is redemptive and powerful. They are best honored by following their example.These Stone Walls came into being one year ago this month. I have Suzanne Sadler to thank for that. She proposed the idea to me after inviting me to write for her blog, Priests in Crisis, at Pentecost last year. "Kill the Priest" received such a broad response that Suzanne asked me to consider writing weekly. These Stone Walls evolved over the month of July last year.My first three posts were about how Saint Maximilian Kolbe came to be a presence in my prison cell, and about the lesson in redemptive suffering I have learned from him. To mark the first anniversary of These Stone Walls, and to help us discern this invitation to membership in the MI and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross, I have rewritten below a compilation of my first posts on These Stone Walls.ST. MAXIMILIAN KOLBE AND THE MAN IN THE MIRRORFor someone on the outside looking in, it must seem an odd place to begin. Virtually every prison cell has one: a small stainless steel sink with a matching toilet welded to its side. Bolted to the cinderblock wall just above it is a small stainless steel mirror, dinged, dented, and scraped so badly that the image it reflects is unrecognizable.I begin each day at the break of dawn in prison by shaving in front of that mirror. This morning ritual has repeated 5,787 times. I seldom cut myself shaving — a minor miracle as I can see very little of me in that mirror. I often think of St. Paul’s cryptic image in his first letter to the Church in Corinth (13:12):

Pornchai and I plan to also Consecrate ourselves as Knights at the Foot of the Cross at Mass on August 15th. I learned from both patrons of These Stone Walls - Saint Maximilian and Saint Pio - that personal suffering offered for others is redemptive and powerful. They are best honored by following their example.These Stone Walls came into being one year ago this month. I have Suzanne Sadler to thank for that. She proposed the idea to me after inviting me to write for her blog, Priests in Crisis, at Pentecost last year. "Kill the Priest" received such a broad response that Suzanne asked me to consider writing weekly. These Stone Walls evolved over the month of July last year.My first three posts were about how Saint Maximilian Kolbe came to be a presence in my prison cell, and about the lesson in redemptive suffering I have learned from him. To mark the first anniversary of These Stone Walls, and to help us discern this invitation to membership in the MI and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross, I have rewritten below a compilation of my first posts on These Stone Walls.ST. MAXIMILIAN KOLBE AND THE MAN IN THE MIRRORFor someone on the outside looking in, it must seem an odd place to begin. Virtually every prison cell has one: a small stainless steel sink with a matching toilet welded to its side. Bolted to the cinderblock wall just above it is a small stainless steel mirror, dinged, dented, and scraped so badly that the image it reflects is unrecognizable.I begin each day at the break of dawn in prison by shaving in front of that mirror. This morning ritual has repeated 5,787 times. I seldom cut myself shaving — a minor miracle as I can see very little of me in that mirror. I often think of St. Paul’s cryptic image in his first letter to the Church in Corinth (13:12): “For now I see dimly, as in a mirror, but then I shall see face to face.” It is a hopeful image. I sometimes find that my mind calculates dates and their meanings on a sort of autopilot. There came a day when I stood at the mirror to shave and realized that on this day - it was Dec. 23, 2006 - I had been a priest in prison for the exact amount of time that I was a priest “on the streets” as prisoners like to describe their lives before prison.From that day until now, I wonder which I see more of in that flawed mirror. Do I see the man who is a priest of 28 years? Or do I see only Prisoner 67546, the identity given to me inside these stone walls? A strange thing happened on the day after I first reflected – as best I could in that mirror — on the person I see.It was Christmas Eve, December 24, 2006, the day that the equation changed. On that day, I was a priest in prison longer than anywhere else. That night at prison mail call, I had a few Christmas cards. One of them was from Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan priest who once visited me in prison.Inside Father McCurry’s Christmas card was a prayer card that is now one of my enduring treasures. It is taped to the stone wall just above the shaving mirror of my cell and has been there ever since the day I received it.The holy card has an image of St. Maximilian Kolbe who offered himself for execution in place of another prisoner in Auschwitz in 1941. The card depicts Father Kolbe in his Conventual Franciscan Habit. He has one sleeve in the striped jacket of his prison uniform with the number 16670 emblazoned across it. There is a scarlet “P” above the number indicating his Polish nationality. He was also a Priest and a falsely accused prisoner. Does either designation extinguish the other? Father Kolbe is at once both, though only one identity was chosen by him.The image is a haunting image for it captures fully that struggle I have so keenly felt. Father Maximilian appeared in my cell just a day after I asked the question of myself. Who am I? I thought at the time that it was a rhetorical question, but it was a prayer. As such, it begged a reply — and got one.MAXIMILIAN AND THIS MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANINGHow I came to be in this prison is a story told elsewhere, by me and by others. How I “met” Father Maximilian Kolbe 60 years after he surrendered his life at Auschwitz is a story about actual grace. Jesuit Father John Hardon defined actual grace as God’s gift of “the special assistance we need to guide the mind and inspire the will” on our path to God. Sometimes, it’s very special.My first three years in prison are a blur in my memory. There is no point trying to find words to express the sense of loss, of alienation, of being cast into an abyss that was not of my own making — a loss that could not be grounded in any reality of my own. A thousand days and nights passed in the abyss before what Father Hardon described as “special assistance” crossed my path.

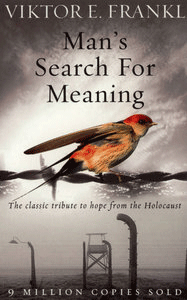

“For now I see dimly, as in a mirror, but then I shall see face to face.” It is a hopeful image. I sometimes find that my mind calculates dates and their meanings on a sort of autopilot. There came a day when I stood at the mirror to shave and realized that on this day - it was Dec. 23, 2006 - I had been a priest in prison for the exact amount of time that I was a priest “on the streets” as prisoners like to describe their lives before prison.From that day until now, I wonder which I see more of in that flawed mirror. Do I see the man who is a priest of 28 years? Or do I see only Prisoner 67546, the identity given to me inside these stone walls? A strange thing happened on the day after I first reflected – as best I could in that mirror — on the person I see.It was Christmas Eve, December 24, 2006, the day that the equation changed. On that day, I was a priest in prison longer than anywhere else. That night at prison mail call, I had a few Christmas cards. One of them was from Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan priest who once visited me in prison.Inside Father McCurry’s Christmas card was a prayer card that is now one of my enduring treasures. It is taped to the stone wall just above the shaving mirror of my cell and has been there ever since the day I received it.The holy card has an image of St. Maximilian Kolbe who offered himself for execution in place of another prisoner in Auschwitz in 1941. The card depicts Father Kolbe in his Conventual Franciscan Habit. He has one sleeve in the striped jacket of his prison uniform with the number 16670 emblazoned across it. There is a scarlet “P” above the number indicating his Polish nationality. He was also a Priest and a falsely accused prisoner. Does either designation extinguish the other? Father Kolbe is at once both, though only one identity was chosen by him.The image is a haunting image for it captures fully that struggle I have so keenly felt. Father Maximilian appeared in my cell just a day after I asked the question of myself. Who am I? I thought at the time that it was a rhetorical question, but it was a prayer. As such, it begged a reply — and got one.MAXIMILIAN AND THIS MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANINGHow I came to be in this prison is a story told elsewhere, by me and by others. How I “met” Father Maximilian Kolbe 60 years after he surrendered his life at Auschwitz is a story about actual grace. Jesuit Father John Hardon defined actual grace as God’s gift of “the special assistance we need to guide the mind and inspire the will” on our path to God. Sometimes, it’s very special.My first three years in prison are a blur in my memory. There is no point trying to find words to express the sense of loss, of alienation, of being cast into an abyss that was not of my own making — a loss that could not be grounded in any reality of my own. A thousand days and nights passed in the abyss before what Father Hardon described as “special assistance” crossed my path. Someone, somewhere — I don’t know who — sent the prison’s Catholic chaplain (a layman then) a book entitled Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, M.D. Somewhere in my studies, I heard of this book, but only a prisoner can read it in the same light in which it is written. The chaplain called me to his office. He wanted to know whether he should recommend this book, but didn’t have time to read it. He wanted my opinion.I didn’t read Dr. Frankl’s book so much as devour it. I read it through three times in seven days. As a priest, I often preached that grace is a process and not an event. It is not always so. I was meant to read Man’s Search for Meaning at the precise moment that it landed upon my path. A week earlier, I may not have been ready. A week later may have been too late. I was drowning in a solitary sea of deeply felt loss. I was not going to make it across. My priesthood and my soul were dying. Man’s Search for Meaning is Viktor Frankl’s vivid account of how he was alone among his family to survive imprisonment at Auschwitz. This was an imprisonment imposed on him for who he was: a Jew.There is a central message in this small book. A profound message, so clear in meaning that it has within it the hallmark of inspired truth. Like Saul thrown from his mount, I remember sinking to the floor when I read it.

Someone, somewhere — I don’t know who — sent the prison’s Catholic chaplain (a layman then) a book entitled Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, M.D. Somewhere in my studies, I heard of this book, but only a prisoner can read it in the same light in which it is written. The chaplain called me to his office. He wanted to know whether he should recommend this book, but didn’t have time to read it. He wanted my opinion.I didn’t read Dr. Frankl’s book so much as devour it. I read it through three times in seven days. As a priest, I often preached that grace is a process and not an event. It is not always so. I was meant to read Man’s Search for Meaning at the precise moment that it landed upon my path. A week earlier, I may not have been ready. A week later may have been too late. I was drowning in a solitary sea of deeply felt loss. I was not going to make it across. My priesthood and my soul were dying. Man’s Search for Meaning is Viktor Frankl’s vivid account of how he was alone among his family to survive imprisonment at Auschwitz. This was an imprisonment imposed on him for who he was: a Jew.There is a central message in this small book. A profound message, so clear in meaning that it has within it the hallmark of inspired truth. Like Saul thrown from his mount, I remember sinking to the floor when I read it.

There is a freedom that no one can ever take from you: The freedom to choose the person you are going to be in any set of circumstances.

This changed everything. Everything! At the very end of his book, Dr. Frankl revealed the name of his inspiration for surviving Auschwitz. He wrote of Sigmund Freud’s cynical view that man is self-serving, that man’s instinctual need for survival will trump quaint notions such as grace and sacrifice every time. For Dr. Frankl, Auschwitz provided the proof that Freud was wrong.That proof was Father Maximilian Kolbe:

“Sigmund Freud once asserted, ‘Let one attempt to expose a number of the most diverse people uniformly to hunger. With the increase of the imperative urge of hunger all individual differences will blur, and in their stead will appear the uniform expression of the one unstilled urge.’ Thank heaven, Sigmund Freud was spared knowing the concentration camps from the inside. His subjects lay on a couch designed in the plush style of Victorian culture, not in the filth of Auschwitz. There, the ‘individual differences’ did not ‘blur’ but, on the contrary, people became more different; people unmasked themselves, both the swine and the saints. And today you need no longer hesitate to use the word ‘saints’: think of Fr. Maximilian Kolbe who was starved and finally murdered by an injection of carbolic acid at Auschwitz and who in 1983 was canonized.” (Man’s Search for Meaning, p. 178)

SANCTITY AND SACRIFICEAs a young priest in 1982, I was only vaguely familiar with the name Maximilian Kolbe. I remember reading of his canonization by Pope John Paul II, but Father Kolbe’s world was far removed from my modern suburban priestly ministry. I was far too busy to step into it.I didn’t know that nearly two decades later, Father Kolbe’s life, death, and example would be proclaimed on the wall of a cell in a prison into which, like Fr. Kolbe, I, too, was thrown just for being a priest.In my post, “In Honor of St. Maximilian Kolbe,” I wrote for those unfamiliar with his story and will repeat it briefly. The prisoners of Auschwitz were packed into bunkers like cattle. To encourage informants, the camp had a policy that if any prisoner escaped, 10 others would be randomly chosen for summary execution.At the morning role call one day, a prisoner from Maximilian’s bunker was missing. Guards chose 10 men to be executed. The 10th fell to the ground and cried for the wife and children he would never see again. Father Maximilian spontaneously stepped forward. “What does this Polish pig want?” The camp commander shouted. “I am a Catholic priest, and I would like to take the place of that man,” said Father Maximilian.Two weeks later, Maximilian alone was still alive among the 10 prisoners chained and condemned to starvation. He was injected with carbolic acid on August 14, 1941, and his remains were unceremoniously incinerated. For the unbeliever, all that Maximilian was went up in smoke. Viktor Frankl shared some other corner of that horrific prison. The story of the person Father Maximilian chose to be rippled through the camp. It offered proof to Viktor Frankl that suffering can as much inspire us by grace as doom us by despair. We get to choose which will define us.I can never embrace these stone walls. I cannot claim ownership of them. Passively acceding to injustice anywhere contributes to injustice everywhere. Father Maximilian never approved of Auschwitz. No one can understand how I now respond to these stone walls, however, without hearing of Father Maximilian’s presence here.Above my mirror, he refocused my hope in the light of Christ. The darkness can never overcome it.I hope you will consider joining my friend, Pornchai, and me as we join Maximilian in offering our struggles in prison as a share in the suffering of Christ. Go to www.marytown.com to prepare your Consecration to St. Maximilian’s own on August 15, the Solemnity of the Assumption.

Viktor Frankl shared some other corner of that horrific prison. The story of the person Father Maximilian chose to be rippled through the camp. It offered proof to Viktor Frankl that suffering can as much inspire us by grace as doom us by despair. We get to choose which will define us.I can never embrace these stone walls. I cannot claim ownership of them. Passively acceding to injustice anywhere contributes to injustice everywhere. Father Maximilian never approved of Auschwitz. No one can understand how I now respond to these stone walls, however, without hearing of Father Maximilian’s presence here.Above my mirror, he refocused my hope in the light of Christ. The darkness can never overcome it.I hope you will consider joining my friend, Pornchai, and me as we join Maximilian in offering our struggles in prison as a share in the suffering of Christ. Go to www.marytown.com to prepare your Consecration to St. Maximilian’s own on August 15, the Solemnity of the Assumption.