The Sacrifice of the Mass Part 1

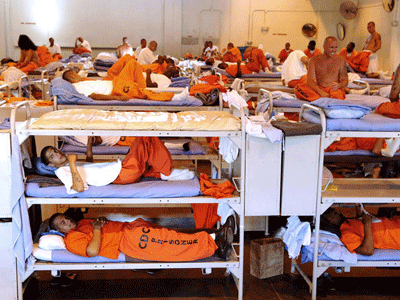

After fifteen years in prison, two remarkable things happened to me in just the last three months. The first was the launch of These Stone Walls in late July. The second, and most remarkable, is the ability to celebrate Mass weekly in my cell. The latter is a story worth telling.For my first five years in prison, I was confined in a cell with seven other men. There was room for nothing else in the cell but steel bunks and yellow plastic bins containing the sum total of each prisoner's possessions: clothing, books, food, and personal items. We prepared meals and hot water for coffee on the concrete floor.A priest came to the prison for Sunday Mass twice a month, but I never saw him. I was in a unit in the prison that did not have access to the prison Chapel and other programs. There is a sort of domino effect when prisoners claim to be wrongly convicted. My declaration of innocence rendered me ineligible for prison programs, and, by extension, for any hope for parole. It also rendered me ineligible for preferred prison housing in the general population.The stereotype that all prisoners claim to be innocent is not at all accurate. Prisoners do not lightly make such a claim. In most prisons, there is an enormous price to pay for it. As one local lawyer put it, a convicted sex offender who says he's sorry and won't do it again will often serve a short sentence, but a middle-aged man who insists he is innocent may die in prison.The cellblock had twenty-four cells each housing eight men. It was filled with the daily cacophony of overcrowded prisoners -80% of them barely in their 20's - trying to occupy and entertain themselves. There was constant, senseless noise.

After fifteen years in prison, two remarkable things happened to me in just the last three months. The first was the launch of These Stone Walls in late July. The second, and most remarkable, is the ability to celebrate Mass weekly in my cell. The latter is a story worth telling.For my first five years in prison, I was confined in a cell with seven other men. There was room for nothing else in the cell but steel bunks and yellow plastic bins containing the sum total of each prisoner's possessions: clothing, books, food, and personal items. We prepared meals and hot water for coffee on the concrete floor.A priest came to the prison for Sunday Mass twice a month, but I never saw him. I was in a unit in the prison that did not have access to the prison Chapel and other programs. There is a sort of domino effect when prisoners claim to be wrongly convicted. My declaration of innocence rendered me ineligible for prison programs, and, by extension, for any hope for parole. It also rendered me ineligible for preferred prison housing in the general population.The stereotype that all prisoners claim to be innocent is not at all accurate. Prisoners do not lightly make such a claim. In most prisons, there is an enormous price to pay for it. As one local lawyer put it, a convicted sex offender who says he's sorry and won't do it again will often serve a short sentence, but a middle-aged man who insists he is innocent may die in prison.The cellblock had twenty-four cells each housing eight men. It was filled with the daily cacophony of overcrowded prisoners -80% of them barely in their 20's - trying to occupy and entertain themselves. There was constant, senseless noise.

HUDDLED MASSES

Late at night, after others would finally sleep, I would huddle in a corner of my bunk. There was not quite enough room to sit up straight because there was another steel bunk just above me. With my book light and a Roman Missal loaned to me by the chaplain, I would "celebrate" Mass surrounded by snoring prisoners. I know these were not valid Masses. I had no elements of bread or wine. All I had were the readings and prayers, and the yearning in my heart for Christ's Presence in this cold, dark place. For five years, that spectral shell of the Mass was all that I had - that, and a single volume breviary from which I prayed the Divine Office each day.During that five years I was moved seventeen times - each time thrown into another cell with seven strangers. By design or not was unclear, but I was kept in a near constant state of adjustment and upheaval.The atmosphere in which I lived day after day is difficult to describe. All the other prisoners knew I was a priest, or quickly found out after I moved in. The mental health of other prisoners is often an issue for anyone in prison. One night in the eight-man cell, I awoke at 3:00 AM smelling smoke. A prisoner with a book of matches was trying to ignite my blankets while I slept, insisting that Satan awoke him in the night and asked him to do so.

I know these were not valid Masses. I had no elements of bread or wine. All I had were the readings and prayers, and the yearning in my heart for Christ's Presence in this cold, dark place. For five years, that spectral shell of the Mass was all that I had - that, and a single volume breviary from which I prayed the Divine Office each day.During that five years I was moved seventeen times - each time thrown into another cell with seven strangers. By design or not was unclear, but I was kept in a near constant state of adjustment and upheaval.The atmosphere in which I lived day after day is difficult to describe. All the other prisoners knew I was a priest, or quickly found out after I moved in. The mental health of other prisoners is often an issue for anyone in prison. One night in the eight-man cell, I awoke at 3:00 AM smelling smoke. A prisoner with a book of matches was trying to ignite my blankets while I slept, insisting that Satan awoke him in the night and asked him to do so. Distinctions between madness and malice blur in prison. One day, I returned to the cell to find my Roman Missal and breviary torn apart, their pages ripped out and flushed down a toilet. None of the seven other prisoners in my cell saw or knew anything. It took six months to replace the books. On another day I returned to find Satanic symbols drawn on the wall next to my bunk.Years later, Cardinal Avery Dulles wrote to me of Father Walter Ciszek, S.J.:

Distinctions between madness and malice blur in prison. One day, I returned to the cell to find my Roman Missal and breviary torn apart, their pages ripped out and flushed down a toilet. None of the seven other prisoners in my cell saw or knew anything. It took six months to replace the books. On another day I returned to find Satanic symbols drawn on the wall next to my bunk.Years later, Cardinal Avery Dulles wrote to me of Father Walter Ciszek, S.J.:

"You are in a position to practice and to propose to others spirituality for the imprisoned. During my retreat this year I read more carefully than before Fr.Walter Ciszek's, He Leadeth Me, with his reflections on five years in solitary and fifteen years of hard labor in Siberia. As I believe I have remarked before, much of the finest Christian literature comes from believers who were unjustly imprisoned.”

In his acclaimed book, With God in Russia (Ignatius Press,1997), Fr. Ciszek described in vivid detail being unjustly imprisoned for twenty years in a Siberian gulag, accused of being a "Vatican spy." He suffered deprivations that made my imprisonment pale by comparison. Father Ciszek also wrote of how he celebrated the Sacrifice of the Mass which he could offer only in his heart:

"After breakfast, I would say Mass by heart - that is, I would say all the prayers, for of course I couldn't actually celebrate the Holy Sacrifice." I said the Angelus morning, noon, and night as the Kremlin clock chimed the hours."

A few readers of These Stone Walls have mentioned Father Ciszek in their messages to me. I feel a special bond with him, especially in my experience of "Midnight Mass" huddled on my steel bunk in a crowded cell with no bread or wine. In prison, faith and spiritual surrender are not to be taken for granted. They were a struggle for Father Ciszek and remain a daily struggle for me.

PRESENCE AND ABSENCE

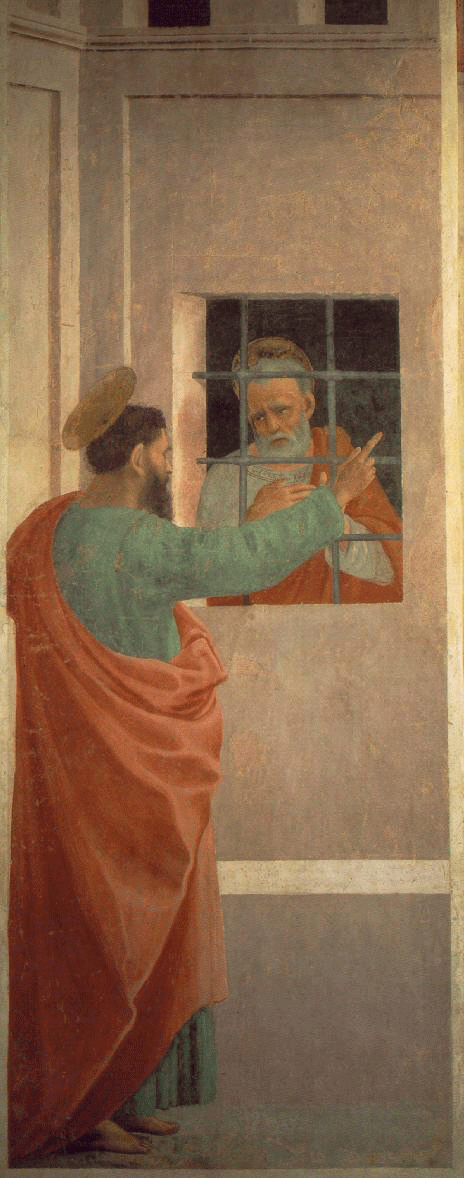

Toward the end of that first five years in prison, a new chaplain arrived, a Catholic deacon. A few weeks after his arrival, I was summoned to his office. He wanted me to read a presentation on Eucharistic Adoration that he had written for the diocesan diaconate program. I sat in his office dutifully reading his essay. When I looked up at one point, I noticed a small wooden tabernacle on a shelf in the corner of the office. The tabernacle was hand carved by a Catholic prisoner, and was incredibly beautiful.Sitting there with the deacon's essay in my hand, I noticed a small Sanctuary Lamp that was lit. I realized with a great jolt that the Blessed Sacrament was in the tabernacle in the deacon's office. I felt overwhelmed, and tears came to my eyes. For the first time in over five years, I was in the Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. The chaplain smiled, apparently thinking that I was reacting to his essay.Years ago as a young priest, I used to play racquetball early in the morning at a fitness center at which some friends gave me a membership. One of my occasional opponents was a local Protestant minister. I had a particularly good corner shot that he could never return. I used to jokingly call it "the Ecumenical Movement." I almost always won, but he was getting pretty good at racquetball so it was a challenge for us both. One day after an early morning game, the minister told me that he finds Catholics to be intriguing.

One day after an early morning game, the minister told me that he finds Catholics to be intriguing.

"If you truly believe that Christ is actually present in that tabernacle in your church," he said, "how can you just go about your day knowing that He is there?"

His words stayed with me for many years. So many times as a priest, I took the Blessed Sacrament for granted. How many times had I passed by in the sanctuary, too busy to pause and ponder this living, enduring Presence in our midst? How many times had a busy day gone by without an hour spent in His Presence?I have come to know on a deeply personal level -through the force of sheer deprivation - the importance of a Holy Hour before the Blessed Sacrament. Many of you have commented here on These Stone Walls that you have devoted an hour of your Eucharistic Adoration for me. That means far more to me than you may know.It's an understatement that "absence makes the heart grow fonder." It is far more than that. My five year absence from Christ in the Eucharist had a more profound impact on me than did prison itself. It left me a spiritual barren wasteland, craving freedom not from stone walls and iron bars, but from the chasm of separation from the Church and Sacraments that many take for granted. I could see why, in our Creed, Christ descended to the dead. We could not come to Him.After those moments before the Blessed Sacrament in the chaplain's office, things fell into place quickly. The new chaplain invited me to celebrate Mass with him in his office weekly, and then he would use the Hosts for his Communion Service with Catholic prisoners.Back in the unit with the crowded cells I had lived in for five years, a guard asked me to volunteer to do some weekly typing. He asked me one day if I would like something in return - perhaps a move to a better place. I asked for an hour's use of a storage room to celebrate Mass in private once per week. It was a strange request for him, but he spoke with his superior. A week later he told me that I may use the storage room alone for one hour each Saturday night from 9:00 to 10:00 PM. It was all that I wanted.The deacon-chaplain provided me with the necessary elements. A seminarian in Vietnam had hand woven a beautiful small stole for me, and sent it to the chaplain who gave it to me. It was a very special possession. It was the very bridge linking me with the Sacramental life of the Church from which I had known five years of alienation. That stole was my greatest treasure.Shortly thereafter, I was moved to another unit in the prison. The cells were much smaller, and housed two prisoners each. Once again, I was thrown among strangers though it was easier for me to find time alone - often late at night - to celebrate Mass in my cell. Then, suddenly and without warning one day, the Chaplain was gone from the prison. After a month, a new Chaplain, another deacon, arrived, but he could not find the items that his predecessor had secured for me for Mass. Shortly after, my cell was searched, and my Mass supplies and stole were taken by a guard. Prisoners are powerless over such things.I was heartbroken as the guard took my stole, and mocked it, and me. He told me that he was an "ex-Catholic" and said he heard that I am "kicked out of the Church" and didn't deserve to have it. He threatened to cite me for theft accusing me of stealing it from the prison Chapel. There was nothing I could do but watch as the guard walked out of my cell with my stole disrespectfully hanging out of his back pocket. It was a crushing blow, and it would be four years before I could restore the privilege of celebrating Mass again.

Then, suddenly and without warning one day, the Chaplain was gone from the prison. After a month, a new Chaplain, another deacon, arrived, but he could not find the items that his predecessor had secured for me for Mass. Shortly after, my cell was searched, and my Mass supplies and stole were taken by a guard. Prisoners are powerless over such things.I was heartbroken as the guard took my stole, and mocked it, and me. He told me that he was an "ex-Catholic" and said he heard that I am "kicked out of the Church" and didn't deserve to have it. He threatened to cite me for theft accusing me of stealing it from the prison Chapel. There was nothing I could do but watch as the guard walked out of my cell with my stole disrespectfully hanging out of his back pocket. It was a crushing blow, and it would be four years before I could restore the privilege of celebrating Mass again.

"Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or the sword? (Romans 8:35-36)

Please read "The Sacrifice of the Mass: Part II" next week.![]()