Maximilian Kolbe: The Other Prisoner Priest in My Cell

Unjustly in prison since 1994, Fr Gordon MacRae began this blog in early August 2009. From his cell he looked into a mirror as a prisoner, but a priest looked back.

August 9, 2023 by Fr Gordon MacRae

“Now we see dimly as in a mirror, but then we shall see face to face. Now I know only in part, but then I shall understand fully even as I am fully understood.”

— 1 Corinthians 13:12

+ + +

At the end of our annual BTSW Christmas Card in December, 2022, we posted a live YouTube feed linked to a beautiful Adoration chapel in Poland sponsored by EWTN. Months later, I wrote a post that was popular with readers around the world. It was “Eucharistic Adoration: Face to Face in Friendship with God.” Its introduction was, “A live internet feed from a Eucharistic Adoration chapel in Poland landed on this blog at Christmas and is now revealed as a gift from a beloved Patron Saint.”

It was only weeks after we posted it that I learned that the live feed was from the chapel of Niepokalanow, the City of the Immaculata founded by St. Maximilian Kolbe prior to his 1941 arrest and imprisonment at Auschwitz where he was martyred. Most of our readers knew what this meant to me. It was a direct link to the Patron Saint of this blog — the saint who inserted himself not only in my life, but in the life of Pornchai Moontri as well. At the time of his Divine Mercy conversion, Pornchai took the name Maximilian as his Christian name.

I have written so many posts about St. Maximilian Kolbe that I cannot write this one in any way that would make it stand out. Maximilian is one of two Patron Saints who stand with me in this imprisonment and in this blog. I mean that literally. The other is Saint Padre Pio.

Oddly enough, I must refer you to a post about Padre Pio for a sense of what the other patron saint has meant to us. That post is “Padre Pio: Witness for the Defense of Wounded Souls.” I will link to it again at the end of this post, but I want to first present an excerpt from it here:

“Among the many letters of Padre Pio to the thousands of pilgrims and penitents who wrote to him was one dated in the year before Padre Pio's death on September 23, 1968. In that letter, Padre Pio advised a suffering soul to enroll in the Knights at the Foot of the Cross, a spiritual movement founded by Father Maximilian Kolbe for the offering of life's wounds as a share in the suffering of Christ. I was amazed to read that Padre Pio had such an awareness of our other patron saint two decades before St. Maximilian Kolbe was canonized.”

I should point out that both saints were canonized by another saint, John Paul II. I wrote the above post in September 2020. It begins with a description of my friend Pornchai Moontri walking with me in the prison yard early in the morning of September 8, 2020. It was the day Pornchai left after nearly 15 years in a prison cell with me. Last week in these pages, I wrote of that journey, of both the heartbreak of change and the challenge of hope. You should not miss that post either. It was, “For Pornchai Moontri, Hope and Hard Work Build a Future.”

The year 2009, when this blog began, was a strange one for us behind these stone walls. It was four years after The Wall Street Journal published the first of many articles exposing prosecutorial corruption in the case that sent me to life in prison in 1994. Judge Arthur Brennan, now retired in New Hampshire, might not agree that he imprisoned me to a “life” sentence, but I was 41 years old when he imposed a 67-year prison sentence on me citing “clear and convincing evidence.”

The “evidence” he cited did not exist, has never existed, and has been exposed as the result of a police officer’s corruption which some entities are working very hard to cover up. I am now 70, and will be 108 when my sentence is over. Even now there is a suggestion that I could see freedom if I just admit guilt.

In my first 12 years in prison from 1994 to 2006, I existed in a sort of mental and spiritual paralysis. Then two things happened in 2006 that altered the course, not only of my life, but of my soul. First, St. Maximilian arrived on my cell mirror. Then, as though on cue, Pornchai Moontri also arrived in my cell. The first thing he ever said to me was in the form of a question. Pointing to the photo on my mirror he asked, “Is this you?”

I could best answer that question today by revisiting the first three posts I wrote for this blog in August, 2009. Don’t worry. I was a lot less long-winded back then. Each of these three earliest posts was but a page or two. Fourteen years later, they hold up well against the test of time, so bear with me please.

+ + +

August, 2009 — St. Maximilian Kolbe and the Man in the Mirror

For someone on the outside looking in, it must seem an odd place to begin. Virtually every prison cell has one: a small stainless steel sink with a matching toilet welded to its side. Bolted to the cinderblock wall just above it is a small stainless steel mirror, dinged, dented, and scraped so badly that the image it reflects is unrecognizable.

I begin each day at the break of dawn in prison by shaving in front of that mirror. This morning ritual has repeated 5,412 times. [At this writing, it is 10,530 times.] I seldom cut myself shaving — a minor miracle as I can see very little of me in that mirror. I often think of St. Paul’s cryptic image in his first letter to the Church in Corinth (13:12): “For now I see dimly, as in a mirror, but then I shall see face to face.” It is a hopeful image.

I sometimes find that my mind calculates dates and their meanings on a sort of autopilot. There came a day when I stood at the mirror to shave and realized that on this day it was Dec. 23, 2006. I have been a priest in prison for the exact amount of time that I was a priest “on the streets” as prisoners like to describe their lives before prison.

From that day until now, I wonder which I see more of in that flawed mirror. Do I see the man who is a priest of 27 years? Or do I see only Prisoner 67546, the identity given to me inside these stone walls?

A strange thing happened on the day after I first reflected — as best I could in that mirror — on who I see. It was Christmas Eve, December 24, 2006, the day that the equation changed. It was the day that I was a priest in prison longer than anywhere else. That night at prison mail call, I had a few Christmas cards. One of them was from Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan priest who once visited me in prison.

Inside Father McCurry’s Christmas card was a prayer card that is now one of my enduring treasures. It is taped to the stone wall just above the shaving mirror of my cell and has been there ever since the day I received it. The holy card has an image of St. Maximilian Kolbe who offered himself for execution in place of another prisoner in Auschwitz in 1941. The card depicts Father Kolbe in his Conventual Franciscan habit. He has one sleeve in the striped jacket of his prison uniform with the number 16670 emblazoned across it. There is a scarlet “P” above the number indicating his Polish nationality. He was also a priest and a falsely accused prisoner. Does either designation extinguish the other? Father Kolbe is at once both, though only one identity was chosen by him.

The image is a haunting image for it captures fully that struggle I have so keenly felt. Father Maximilian appeared in my cell just a day after I asked the question of myself. Who am I? I thought at the time, that it was a rhetorical question, but it was a prayer. As such, it begged a reply — and got one.

+ + +

August, 2009 - Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part I

How I came to be in this prison is a story told elsewhere, by me and by others. How I “met” Father Maximilian Kolbe 60 years after he surrendered his life at Auschwitz is a story about actual grace. In his Catholic Catechism, Jesuit Father John Hardon defines actual grace as God’s gift of “the special assistance we need to guide the mind and inspire the will” on our path to God. Sometimes, it’s very special.

My first three years in prison are a blur in my memory. There is no point trying to find words to express the sense of loss, of alienation, of being cast into an abyss that was not of my own making — a loss that could not be grounded in any reality of mine. About 1,000 days and nights passed in the abyss before what Father Hardon described as “special assistance” crossed my path.

Someone, somewhere — I don’t know who — sent the prison’s Catholic chaplain (a layman then) a book entitled Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, M.D. Somewhere in my studies, I heard of this book, but only a prisoner can read it in the same light in which it was written. The chaplain summoned me to his office. He wanted to know whether he should recommend this book, but didn’t have time to read it. He wanted my opinion. It had been years since anyone had asked my opinion on anything.

I didn’t read Dr. Frankl’s book so much as devour it. I read it through three times in seven days. As a priest, I often preached that grace is a process and not an event. It is not always so. I was meant to read Man’s Search for Meaning at the precise time that it landed upon my path. A week earlier, I would not have been ready. A week later may have been too late. I was drowning in the solitary sea of deeply felt loss. I was not going to make it across. My priesthood and my soul were dying.

The Book, as I have come to call it, is Viktor Frankl’s vivid account of how he was alone among his family to survive imprisonment at Auschwitz. This was an imprisonment imposed on him for who he was: a Jew. There is a central message in this small book. A profound message, so clear in meaning, that it has within it the hallmark of inspired truth. Like Saul thrown from his mount to become Paul, I remember sinking to the floor when I read it

“There is a freedom that no one can ever take from you: The freedom to choose the person you are going to be in any set of circumstances.”

This changed everything. Everything! You will see how later. At the very end of his book, Dr. Frankl revealed the name of his inspiration for surviving Auschwitz. He wrote of Sigmund Freud’s cynical view that man is self-serving. And a man’s instinctual need to survive will trump “quaint notions” such as grace and sacrifice every time. For Dr. Frankl, Auschwitz provided the proof that Freud was wrong.

That proof, he wrote, was Father Maximilian Kolbe . . . .

+ + +

August, 2009 — Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part II

As a young priest in 1982, I was only vaguely familiar with the name Maximilian Kolbe. I remember reading of his canonization by Pope John Paul II, but Father Kolbe’s world was far removed from my modern suburban priestly ministry. I was far too busy to step into it. I didn’t know that nearly two decades later, Father Kolbe’s life, death, and sainthood would be proclaimed on the wall of my prison cell. I also didn’t know that this would help define the person I choose to be in prison.

Being a Jew and not a Catholic, Dr. Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning, said nothing about Maximilian’s sainthood or any miracles attributed to his intercession. Instead, Dr. Frankl was moved by the profound charity of Maximilian, which defied the narcissism of our times. For those unfamiliar with him, the story is simple.

The prisoners of Auschwitz were packed into bunkers like cattle. To encourage informants, the camp had a policy that if any prisoner escaped, 10 others would be randomly chosen for summary execution. At the morning roll call one day, a prisoner from Maximilian’s bunker was missing. Guards chose 10 men to be executed. The 10th fell to the ground and cried for the wife and children he would never see again. Father Kolbe spontaneously stepped forward. The camp commandant stopped the selection process and demanded, “Who is this Polish swine?” Father Maximilian answered, “I am a Catholic priest, and I would like to take the place of this man.”

Two weeks later, he alone was still alive among the 10 prisoners chained and condemned to starvation. Maximilian was injected with carbolic acid on August 14, 1941, and his remains unceremoniously incinerated. For the unbeliever, all that Maximilian was went up in smoke and ash to drift in the sky above Auschwitz.

Viktor Frankl shared some other corner of that horrific prison. The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us.

Within days of reading Man’s Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe’s sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue. Conventual Franciscan Father James McCurry had been in an airport in Ireland when he heard an Irish priest nearby mention that he corresponds with a priest in a Concord, New Hampshire prison. Father McCurry said he was on his way to visit his order’s house in Granby, Massachusetts and would arrange to visit the Concord prison. Weeks later, Father McCurry and I met in the prison visiting room. When I asked him what his “assignment” is, he said, “Well I just finished a biography of St. Maximilian Kolbe. Have you heard of him?”

Father McCurry went on to say that he was the Vice Postulator in Rome for the cause of Saint Maximilian’s canonization. He had met the man whose grandfather’s life was saved by Father Kolbe. A few years later, Father McCurry arranged a Father Maximilian Kolbe exhibit at the National Holocaust Museum. It was then that he sent me the card depicting Father Maximilian clothed in his Franciscan habit with one sleeve in his prison uniform. I keep the card above my mirror in my cell.

I can never embrace these stone walls. I can’t claim ownership of them. Passively acceding to injustice anywhere contributes to injustice everywhere. Father Maximilian never approved of Auschwitz.

One can’t understand how I now respond to these stone walls, however, without hearing of Father Maximilian’s presence there. Above my mirror, he refocused my hope in the light of Christ. The darkness can never overcome it. What hope and freedom there is in that fact! The darkness can never, ever, ever overcome it!

+ + +

August 2023

The events described in the three short posts above were published in August, 2009, but they took place in 2006 and 2007. In early 2007 a young man named Pornchai Moontri arrived in this prison after a lifelong passage through the depths of hell. Following 14 years in and out of solitary confinement in a Supermax prison in the state of Maine, Pornchai was transferred to the Concord, NH prison. One day he was dragging a trash bag with his life’s belongings through the cell block where I lived. My door just happened to be open. He stopped in front of it and looked at me with deep hostility in his eyes. It was not the person he chose to be, but rather the person he felt he had to be.

Pornchai looked into my cell and looked directly at the mirror above my sink. He pointed to the image of Saint Maximilian and said, “Is this you?”

Three years later, when Pornchai was received into the Catholic faith on Divine Mercy Sunday 2010 he became — like Saul thrown from his horse to become Paul — Pornchai Maximilian Moontri.

+ + +

Note from Fr Gordon MacRae : Thank you for reading and sharing this post which now incorporates my first three posts from Beyond These Stone Walls. On August 9, the day this is posted, the Church also honors another martyr of Auschwitz, St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, the Carmelite scholar formerly known as Edith Stein. We hope you might want to read a bit further with these posts:

Saints and Sacrifices : Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein at Auschwitz

A Tale of Two Priests : Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul II

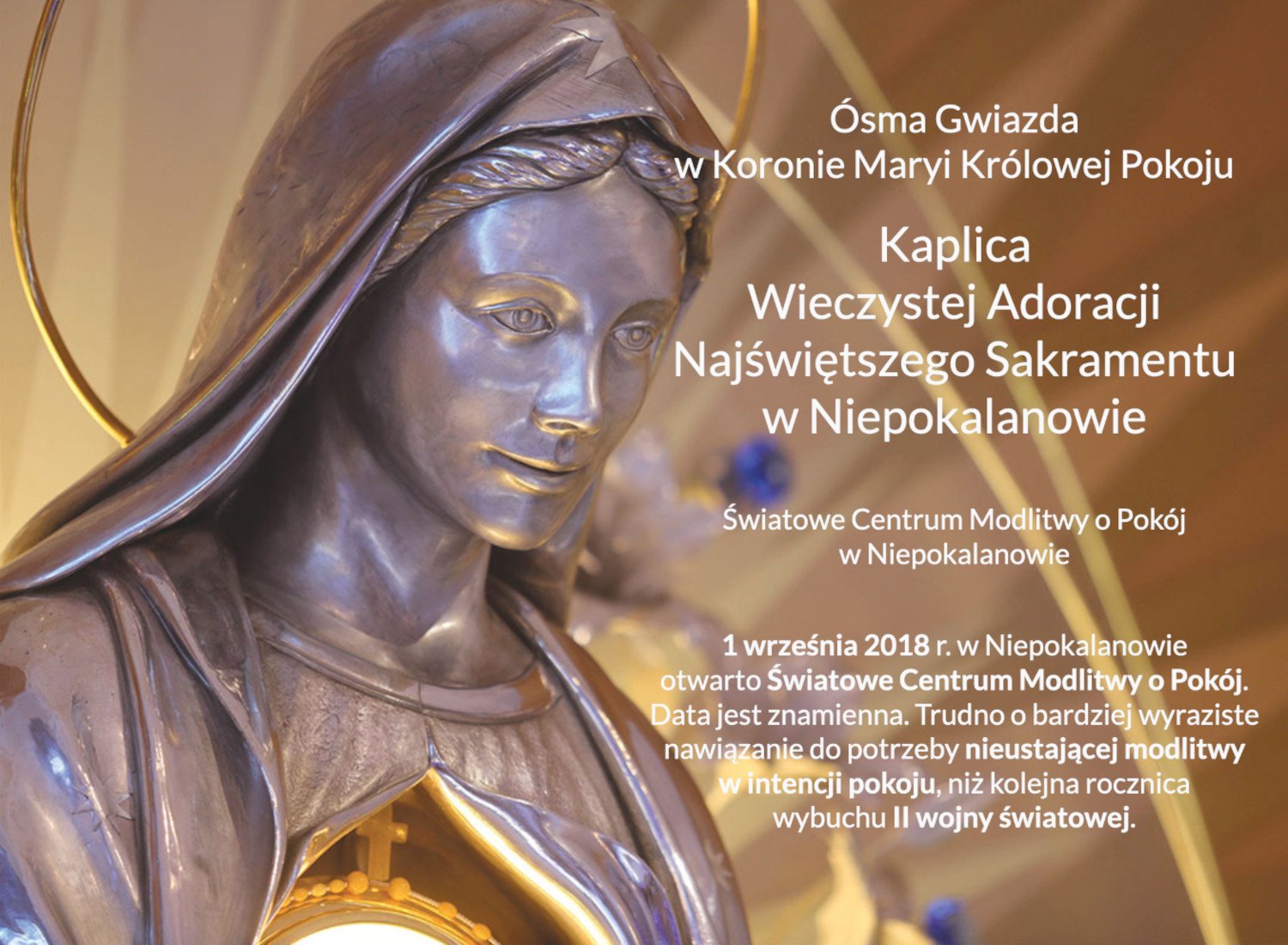

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap the image for live access to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”