“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Pornchai Moontri, Citizen of the Kingdom of Thailand

Pornchai Moontri waited 29 years for the image atop this post. His citizenship in the Kingdom of Thailand and his life in Divine Mercy have now come full circle.

Pornchai Moontri waited 29 years for the image atop this post. His citizenship in the Kingdom of Thailand and his life in Divine Mercy have now come full circle.

November 3, 2021

High school and college students from Chile to China have accessed and downloaded one of my most-visited posts, “Les Miserables: The Bishop and the Redemption of Jean Valjean.” When I wrote it, I did not intend it to be a source for book reviews, but I'm happy to be of service. With over a century of reflection on this longest and most famous of Victor Hugo’s works, the redemption of a former prisoner and the Catholic bishop who set it in motion are what many people find most inspiring.

Jean Valjean is the main character in Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, Les Miserables, about injustices in Nineteenth Century French society. At the time he wrote it, Hugo had been exiled by Emperor Napoleon to the Isle of Guernsey. Like the Amazon “woke” of today, Napoleon censored and suppressed many writers and their works.

After 19 years in prison for stealing a loaf of bread, Jean Valjean was condemned to live on-the-run with self-righteous Inspector Javert in constant pursuit. Near starvation himself, Valjean stole two silver candlesticks from the home of a Catholic bishop. When caught, the bishop stated that the police were misinformed: “The silver was a gift,” he said. That set in motion a story of two of literature’s most noble figures, Jean Valjean and Bishop Bienvenue.

One of the great ironies of the novel is something I wrote about in the above post. After reading a draft, Victor Hugo’s adult son wanted the character of the bishop replaced with someone whose honesty and integrity would seem more realistic in Nineteenth Century France. He wanted the bishop replaced by a lawyer.

I hope most of our readers have by now divested themselves of the notion that everyone in prison is a criminal. It is not true and has never been true. And I hope readers recognize that there is nothing more essential for someone emerging from prison than a sense that he or she belongs somewhere. Being lost without hope in prison only to become lost without hope in freedom crushes all that is left of the human spirit.

This is something that, 16 years ago, I vowed would not happen to my friend, Pornchai Moontri. We were faced with the prospect that he would emerge from prison, and in a foreign land, after nearly 30 years incarcerated for an offense committed as a youth, an offense that someone else set in motion. The clear and compelling evidence for that is laid out in my post, “Human Traffic: The ICE Deportation of Pornchai Moontri.”

You know the rest of what happened. It is terribly painful to read, but no one should let that story pass by. Pornchai’s “going home” was far more complicated than most. He had a home as a poor but happy eleven-year-old. Having been abandoned by his single parent mother at age two, he grew up with an aunt and cousins who lived a simple, but by no means privileged, life. They loved him, and that counts for an awful lot in life. Then at age eleven he was suddenly taken away by a total stranger.

Pornchai at age 12 just after his arrival in America, and just before the events of this post took place. To the right, Pornchai prays at the tomb of his mother for the first time upon his arrival in Thailand in March 2021.

Home Is Where the Heart Is, Even If Broken

If you have been a regular reader of these pages, then you already know the circumstances that took Pornchai Moontri, at age 11, from the rice paddies and water buffalo of his childhood in the rural north of Thailand to the streets of Bangor, Maine. America was dangled before him with a promise that he would never be hungry again. The reality was very different. He was a victim of human trafficking. His mother, the only other person who knew of the horrific abuse inflicted on him, was murdered.

At age 14, Pornchai escaped from his nightmare existence into life on the streets of Bangor, Maine, a homeless adolescent stranded in a foreign land. On March 21, 1992, at age 18, he was attacked in a supermarket parking lot for trying to drown his sorrows in a shoplifted can of beer. In the struggle, a life was lost and Pornchai descended into despair. He was sent to prison into the madness of long term solitary confinement. Then, 14 years later, broken and lost, he was moved to another prison and was moved in with me.

In 2020, Pornchai was taken away again from his home — this time “home” was the 60-square-foot prison cell that he shared with me for the previous 15 years. During those years he had a dramatic Catholic conversion and committed himself and his life to Divine Mercy. He graduated from high school with high honors, earned two additional diplomas, and excelled in courses of Catholic Distance University. He became a mentor for younger prisoners, and a master craftsman in woodworking.

After 29 years in prison since age 18, 36 years after being taken from his home at age eleven, after five months in grueling ICE detention despite all the BS promises of a “kinder, gentler President” in the White House, Pornchai was left in Bangkok, Thailand on February 9, 2021 at age 47.

Sitting in my prison cell one night in late September 2021, a tiny number “1” suddenly appeared above the message icon on my GTL tablet. Unlike your email, the GTL tablet system for sale to prisoners is all about enhancing the GTL Corporation, not the prison or the prisoner. At $150 for the tablet, $.40 for each short message, $1.00 for a photo attachment, and $2.00 for a 15-second video, it feels exploitive. But after 27 years without electronic communication, the sight of that tiny number at the icon makes my heart jump a bit.

The message was from Pornchai Moontri in Thailand. It had a 15-second video clip that I wish I could post for you. We will have to settle for my description. In a dark prison cell in Concord, New Hampshire, I reached for my ear phones hoping that the brief video also had audio. It did. When I opened it, I saw my friend, Pornchai seated at a table in the dark with a small cake and a few lit candles illuminating his face.

Several people stood around Pornchai chanting “Happy Birthday” in Thai. There was a unified “clap-clap-clap” after each of several verses of the chant. Then, surrounded by the family of his cousin whom he last saw when they lived as brothers at age 11 in 1985, Pornchai distinctly made the Sign of the Cross, paused, and blew out the candles. There was an odd moment of silence just then. A sense that some hidden grace had filled the room. His cousin looked upon him with a broad smile, captured in the images below.

In my own darkness many thousands of miles away from this scene, I choked up as I took in this 15-seconds of happiness. I miss my friend, but my tears were not of sadness. They were of triumph. This was Pornchai’s 48th birthday and his first in freedom from the heavy crosses of his past.

And the Sea Will Surrender Its Dead

With the help of a few readers who contributed to the cause, I sent Pornchai some birthday funds to enable him to travel a few hours away for a week at the Gulf of Thailand to see the ocean for the first time in his life, and to connect with his cousin, now an officer in the Royal Thai Navy. As children in 1985, they lived together in the village of Phu Wiang (pronounced “poo-vee-ANG”), the place of Pornchai’s birth in the far rural northeast of Thailand. This seaside reunion with his cousin after 36 years was like a balm on the pain of the past as though the sea had surrendered its dead.

As I write this post, Pornchai is back in Phu Wiang, a 9-hour drive from Bangkok, accompanied by Fr John Hung Le, SVD and Pornchai’s Thai tutor, Khun Chalathip. Since his arrival in Thailand in February of 2021, this is his third visit to the shadowy memories of the place he once knew as home. I described his traumatic first visit there accompanied by Father John — to whom I am much in debt.

Then there was a second trip, again nine hours north accompanied by Father John whose order’s Thai headquarters were just a few kilometers from Pornchai’s place of birth. It is mind-boggling to me that the Holy Spirit had previously drawn together all these threads of connection. That second visit was his second attempt to secure his National Thai ID. It is generally issued at age 16 in Thailand to ratify citizenship and entry into adulthood, but through no fault of his own, Pornchai was not present to receive it.

The first trip to apply for the Thai ID was met with bureaucratic disappointment. I described that first pilgrimage to home in, “For Pornchai Moontri a Miracle Unfolds in Thailand.” Discouraged, Pornchai was told that he will have to return at some future date while documents are again processed through Bangkok and the Thai Embassy in Washington.

The second journey seemed more hopeful. Pornchai was accompanied by not only Father John, but by someone I wrote about in “Archangel Raphael on the Road with Pornchai Moontri.” Pornchai was still told to come back later to apply again. He felt like the Tin Man standing before the Wizard of Oz pleading for his heart. Then, on October 11, 2021 the third pilgrimage was a success. Pornchai was elated to have the image atop this post, and so was I. It represents an accomplishment for which we both struggled for 16 years from inside the same prison cell where I sat that night watching the video of his first birthday in freedom.

That was 16 years together in a place not exactly known for happy endings, redemptive outcomes, and a state of grace. Pornchai and I handed our lives over to Divine Mercy. In the end, as you know if you have kept up, it turned out that even in prison Saint Paul was right. In a place “Where sin increased, grace abounded all the more.” (Romans 5:20)

+ + +

A Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Please visit our Special Events page for information on how to help me help Pornchai in the daunting task of reclaiming his life and future in Thailand after a 36 year absence. I am also doing all I can to assist Fr. John Hung Le, SVD, who delivers rice to impoverished families during the pandemic lockdown. Thailand’s migrant families have been severely impacted since the Delta variant emerged there.

You may also wish to read and share these related posts:

For Pornchai Moontri, a Miracle Unfolds in Thailand

Archangel Raphael on the Road with Pornchai Moontri

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

Don’t forget to visit our new feature Voices from Beyond.

Pornchai, Father John Le, and Pornchai’s Thai tutor Khun Chalathip after Mass at the village Church of Saint Joseph in Phu Wiang, Thailand, October 24, 2021.

Our Lady of Guadalupe Led Pornchai Moontri from His Prisons

The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is the setting for a profound story of how Mother Mary sought out a son lost in darkness and led him to the light of Divine Mercy.

The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is the setting for a profound story of how Mother Mary sought out a son lost in darkness and led him to the light of Divine Mercy.

“The Marians believe Mary chose this particular group of inmates to be the first. That reason eventually was revealed. It turns out that one of the participating inmates was Pornchai Moontri.”

Felix Carroll, “Mary Is At Work Here,” Marian Helper magazine

This story describes a most unlikely series of events in a most unlikely series of places. Some of it has been told in these pages before, but putting theses threads together in one place creates an inspiring tapestry of Divine Providence. I first thought of writing about this several months ago at the conclusion of a six-week retreat program in the New Hampshire State Prison.

Over the summer of 2019, Pornchai Moontri and I were asked to take part, for a second time, in the Divine Mercy retreat, 33 Days to Morning Glory by Marian Father Michael Gaitley. It was offered here in the summer months amid lots of competing activities. The organizers needed 15 participants to host the retreat, but only 13 signed up. So Pornchai and I were to be “the filler.”

We ended up benefitting greatly from the ‘retreat,’ and I think we also contributed much to the other participants. At the end of it, one of the retreat facilitators, Andy Bashelor turned to Pornchai and said “I want you to know that I saw your conversion story. It is the most powerful story I have ever read.” I wrote of this in “Eric Mahl and Pornchai Moontri: A Lesson in Freedom.”

But before returning to that story, I want to revisit something that happened several months before it was posted. Late in the afternoon of December 11, 2018, I was at my desk in the prison Law Library where I use two computer systems side by side. Neither can be used for my own work. I still write posts on an old typewriter.

One computer at my work desk connects directly to Lexis Nexus, a legal database that all law libraries have. The other connects to the prison library system database. As I was shutting down the computers before leaving for the day, I decided to change the background screen on that second computer. For the previous two years it was a graphic image of our Galaxy with a little “You Are Here” arrow pointing to a tiny dot in the cosmos that depicted our solar system. It made me feel very insignificant.

I had but moments left before rushing out the door at 3:00 PM. I called up a list of background screens which displayed only hundreds of numbered graphic files with no way to view them. So I decided to just pick a number – there were pages of them — and get what I get. Then I shut down the system without seeing it.

The next morning, December 12, I arrived at my desk and booted up the computer for work. The image that filled my screen is the one you see here. It’s a magnificent mural in Mexico City. I was not yet even conscious of the date. On the Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, from a thousand random numbers, she appeared on my screen and has been there since.

I was not always conscious of any spiritual connection with Mary. Her sphere of influence in my life was first directed to Pornchai Moontri. The segment from Marian Helper magazine atop this post attests to that. I wrote of it in “Crime and Punishment on the Solemnity of Christ the King.”

A Mystery in Her Eyes

But back, for a moment, to Our Lady of Guadalupe which became my favorite among all the Marian images I have come to reverence. Its origin is fascinating. Nearly five centuries ago, on the morning of December 12, 1531, young Juan Diego, an early Aztec convert to Catholicism in the New World, was walking at the foot of Tepayac Hill outside Mexico City.

Days earlier in the same location, Juan Diego heard the beautiful voice of a lady, but saw no one. On this day, she appeared. She instructed Juan Diego to build a church on that spot. She then told him to gather up in his tilma — a shawl that was commonly worn at the time — a bunch of Castillian roses that appeared nearby. Castillian roses were never in bloom in December, but there they were. He was told to bring these to the local bishop.

When Juan Diego removed his tilma in the presence of the bishop and a group of people with him, he and they were surprised to see the roses. But they were stunned to also see imprinted in the tilma an amazing image of a beautiful young woman surrounded by the rays of the Sun with the crescent moon under her feet, surrounded by roses and with angels attending her. The woman had asked Juan Diego to tell the bishop that she is “Coatloxopeuh,” which in Nahuati, the language of the Aztecs, means “The One Who Crushes the Serpent.”

Juan Diego’s tilma, a garment of the poor, was made of coarse fiber completely unsuitable for painting. Since 1666, the tilma image has been studied by artists and scientists who have been unable to explain how the image became incorporated into the very fibers of the tilma. The shawl is the only one of its kind still in existence after nearly 500 years. It is enshrined in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico.

Hundreds of years later, in 1929, a photographer revealed that when he enlarged photographs of the Lady’s face on the tilma, other images appeared to be in her eyes. In 1979, scientist and engineer, Dr. Jose Aste Tousman, studied the tilma using more sophisticated imaging equipment enlarging her eyes 2,500 times.

After filtering and processing the images using computers, it was discovered that the Lady’s two eyes contain another imprint — the image of the bishop and several other people staring at the tilma apparently at the moment Juan Diego presented it in 1531. It was a permanent imprint equally appearing upon the retinas of both eyes in stereoscopic vision. It appeared to be what Our Lady of Guadalupe saw when Juan Diego first presented his mysterious tilma to the bishop.

On January 26, 1979, Pope John Paul II offered Mass in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe before an overflow crowd of 300,000. Years later, St. Juan Diego was canonized by him. Now, seemingly by random “accident,” that image is enshrined on the computer screen in the place where I work in prison each day. The mathematical odds against this happening are as astronomical as the odds against the image itself.

Her Summons to Pornchai Moontri

The icon of Our Lady of Guadalupe is now also on the wall of our cell. It has been widely accepted by many as a representation of the “Woman Clothed with the Sun and the Moon Under Her Feet” as described in the Book of Revelations (12:1). In the Mystical City of God, Venerable Mary of Agreda discerned that evil greatly fears this image, and flees from it.

Both Sacred Scripture and Catholic Tradition are filled with accounts of good men and women who suffer terrible ordeals only to be transformed into great men and women. I told the devastating story of how Pornchai Moontri came into my life in 2005 and all that he endured before and after in “Pornchai Moontri: Bangkok to Bangor, Survivor of the Night.”

Seemingly by some mysteriously Guiding Hand, the events of both our lives steered us toward the point of our being in the same place at the same time and meeting. After all that Pornchai had suffered in life, he would have had nothing to do with me if not for a 2005 set of articles about me that Dorothy Rabinowitz wrote in two parts in The Wall Street Journal (“A Priest’s Story”).

Pornchai read them and was moved that he has met a friend whose life had been unjustly shattered in almost equal measure to his own. It was then that he made a decision to trust me.

In 2007, the next catastrophe in his life took place. After fifteen years in prison, many of them in the cruel torment of solitary confinement, Pornchai was ordered by a U.S. Immigration Judge to be deported to his native Thailand upon completion of his sentence. Pornchai despaired about the prospect of one day being left alone in a country of only vague memories, a country from which he was taken against his will as a young abandoned child.

I told Pornchai in 2007 that we will have to build a bridge to Thailand. He scoffed at this, saying that it was impossible to do from a prison. Then the first sections of the bridge began to be laid out. This was two years before These Stone Walls began in 2009. First, Mrs. LaVern West, a retired librarian in Cincinnati, Ohio also read those WSJ articles and began corresponding with me.

In a return letter, I mentioned my friendship with Pornchai and the challenges we faced. LaVern began researching and printing rudimentary lessons of Thai language and culture and sending them to Pornchai who began to study them. One of the lessons mentioned a Thai language series produced by Paiboon Publishers, a Thai language bookseller in California. So I wrote to them. Pornchai had not heard Thai spoken since before he became a homeless 13 year-old lost in America.

Paiboon Publishers donated a set of Thai language DVDs to the prison library for the exclusive use of Pornchai to study Thai several hours per week. He quickly became proficient in the spoken language of his early childhood. Writing in Thai, however, was simply beyond his grasp. Mine too.

We both gave learning the Thai writing system a serious effort, but it seems just a complex series of squiggles beyond the capacity of most Western adult minds to assimilate. Pornchai reads and writes fluently in English, however, which in Thailand is an asset.

In 2008, the Catholic League for Religious & Civil Rights published “Pornchai’s Story” as the conversion story of 2008. In 2009, These Stone Walls began, and I also began a quest to make our presence known in Thailand. On the Tenth Anniversary of this blog — in “Prison Journal: A Decade of Writing at These Stone Walls” — I told the story of how it started and the impact it has had on both our lives.

Charlene Duline, a reader of These Stone Walls from Indianapolis, wrote a post for her own blog entitled “Pornchai Moontri is Worth Saving.” I scoffed at it. It was an appeal for an attorney to help Pornchai, but my experience with lawyers left me very pessimistic. Across the globe, trademarks attorney Clare Farr read it and began an investigation into the life of Pornchai in both Thailand and the State of Maine.

My efforts to reach out to Thailand at first seemed to no avail. Everything written and mailed from prison bears a disclaimer stamped on our envelopes declaring that the contents were written and mailed from prison. With only a few exceptions, my letters to anyone I thought might help us were met with silence. Meanwhile, Pornchai was brought into the Church on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010. This resulted in several articles and a chapter in the book, Loved, Lost, Found, by Marian Helper Editor, Felix Carroll. [Editor’s note: that chapter is reprinted with permission with important pictures and a stunning video link to a PBS Frontline documentary about the solitary confinement prison cells where Pornchai spent seemingly endless years. This is to be found at the website dedicated to Pornchai: MercyToTheMax.com]

The book was especially powerful, and it made its way to Bangkok where it was read by a prominent group of Catholics who founded a Divine Mercy mission and ministry. The rest is told gloriously in a post I will link to at the end: “Knock and the Door Will Open: Divine Mercy in Bangkok, Thailand.”

My Surrender to Her Fiat

I gradually became aware that what I once thought and hoped was a Great Tapestry of God designed to rescue me was really designed to rescue Pornchai Moontri, and I was but an instrument in a Divinely inspired Script. It became increasingly clear to me why Mary sent another of her spiritual sons, St Maximilian Kolbe, into our lives.

I came to understand in my heart and soul that I am to emulate what he did. I am to offer my life — or at least my freedom — for the salvation of another prisoner upon whom Mary has placed the safety of her mantle. This is how we got to where we are.

Pornchai’s survival has taken on a life of its own as a result of our growing years of trust in Divine Mercy. The Divine Mercy Thailand group has obtained a commitment from the Redemptorists of Thailand and The Father Ray Foundation to receive Pornchai for a period of adjustment and re-assimilation into Thailand and its culture.

I am trying to raise his room & board for a year. When prisoners are deported from America, they are left in a foreign country with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Without contacts in the receiving country, many are doomed. We have learned much about the process of forced deportation from our experience with others. (See: “Criminal Aliens: The ICE Deportation of Augie Reyes.”)

Late on the night of November 22, 2019, I watched on EWTN as Pope Francis was greeted in Thailand in a beautiful ceremony as Thai Catholics in a predominantly Buddhist culture sang for him like an angelic choir. I realized I will be handing Pornchai over to them in a matter of months, and I could not contain my emotions any longer. As Pornchai was fast asleep late at night as I watched Pope Francis being received in Thailand, I began to cry.

I do not know where our long road turns next, but what started as tears of loss and sorrow that night were also tears of triumph. They were the tears of St. Joseph, summoned to a Fatherhood he never envisioned but from which he would never retreat. Through grace, and the gifts of powerful advocates in Heaven and on Earth, we did all this from inside a prison cell in Concord, New Hampshire. At every turn I heard Mary’s Fiat to Divine Providence: “Be it done to me according to Thy Word.”

O come, O come Emmanuel,

And ransom captive Israel,

That mourns in lonely exile here

Until the Son of God appear.

Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel

Shall come to thee, O Israel.

For more on the above story, please read and share these related posts from Father Gordon MacRae:

The Paradox of Suffering: An Invitation from St. Maximilian Kolbe

Knock and the Door Will Open: Divine Mercy in Bangkok Thailand

When Justice Came to Pornchai Moontri, Mercy Followed by Attorney Clare Farr

We invite you to like and follow Beyond These Stone Walls Facebook.

Please share this post!

An Important Message from Ryan A. MacDonald:

To the Readers of These Stone Walls:

I have had the honor of twice interviewing Pornchai Maximilian Moontri behind those stone walls, and have written about him. As so many of you know, his story is staggering in the depths of its sorrow and yet inspiring in the heights of his spiritual conversion.

TSW reader Bill Wendell from Ohio has kicked off a funding effort with a gift of $1,000 to assist in the restoration of Pornchai’s life. Readers who wish to join in this effort may do so using the PayPal link at Contact & Support. Please indicate on the PayPal form memo line the name of Pornchai Moontri. You may also have a check made out to Pornchai Moontri forwarded to him at Pornchai Moontri c/o These Stone Walls, P.O. Box 205, Wilmington MA 01887-0205. In either case, these funds will be forwarded to a savings account set aside for Pornchai-Max who will be starting his life over. Thank you.

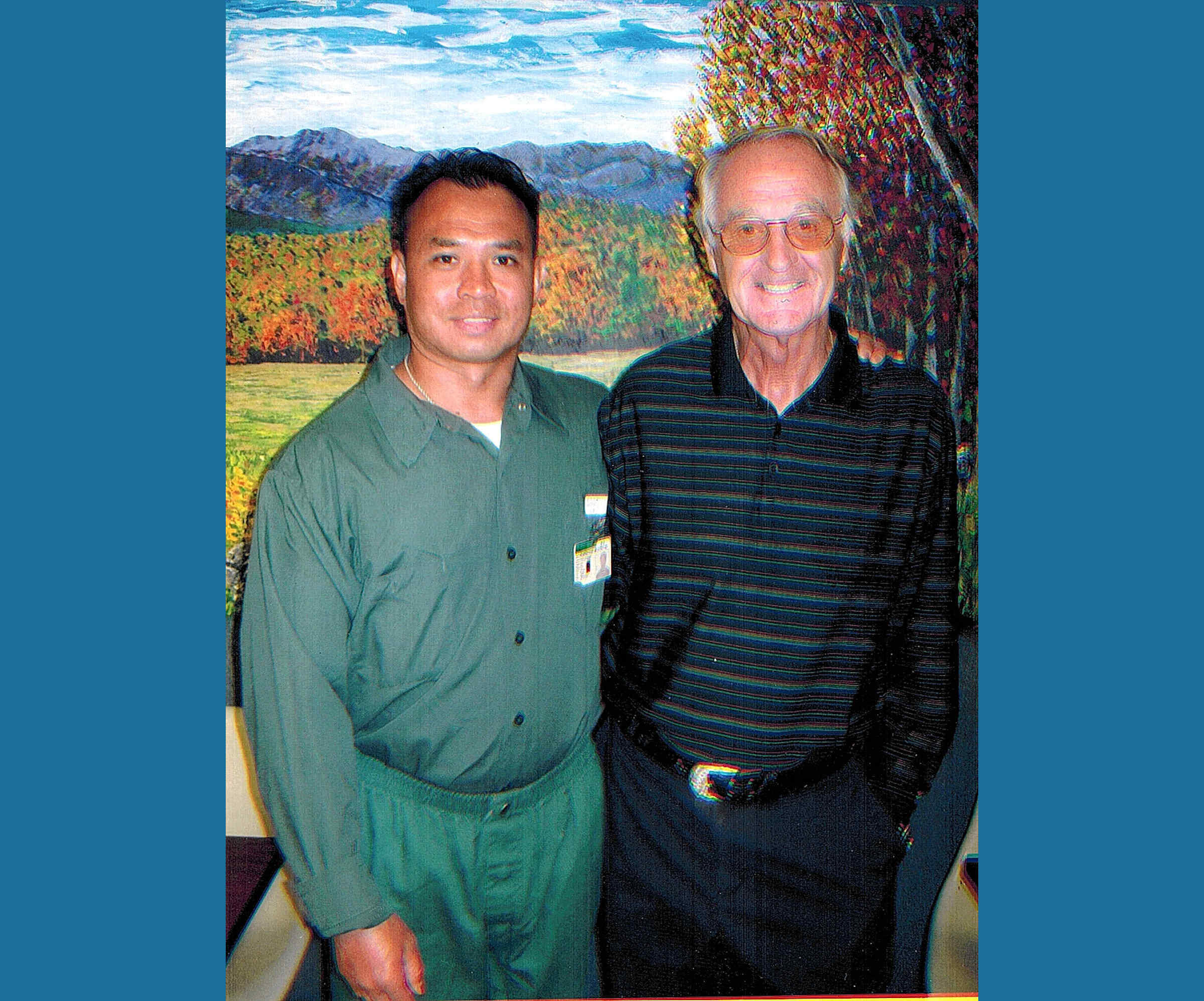

Pictured above: Pornchai Moontri with Viktor Weyand, his sponsor from Divine Mercy Thailand.

Pornchai Moontri: Bangkok to Bangor, Survivor of the Night

This is the long-awaited story of Pornchai Moontri and Fr. Gordon MacRae, two lives denied justice and deprived of hope that converged upon the Great Tapestry of God.

This is the long-awaited story of Pornchai Moontri and Fr. Gordon MacRae, two lives denied justice and deprived of hope that converged upon the Great Tapestry of God.

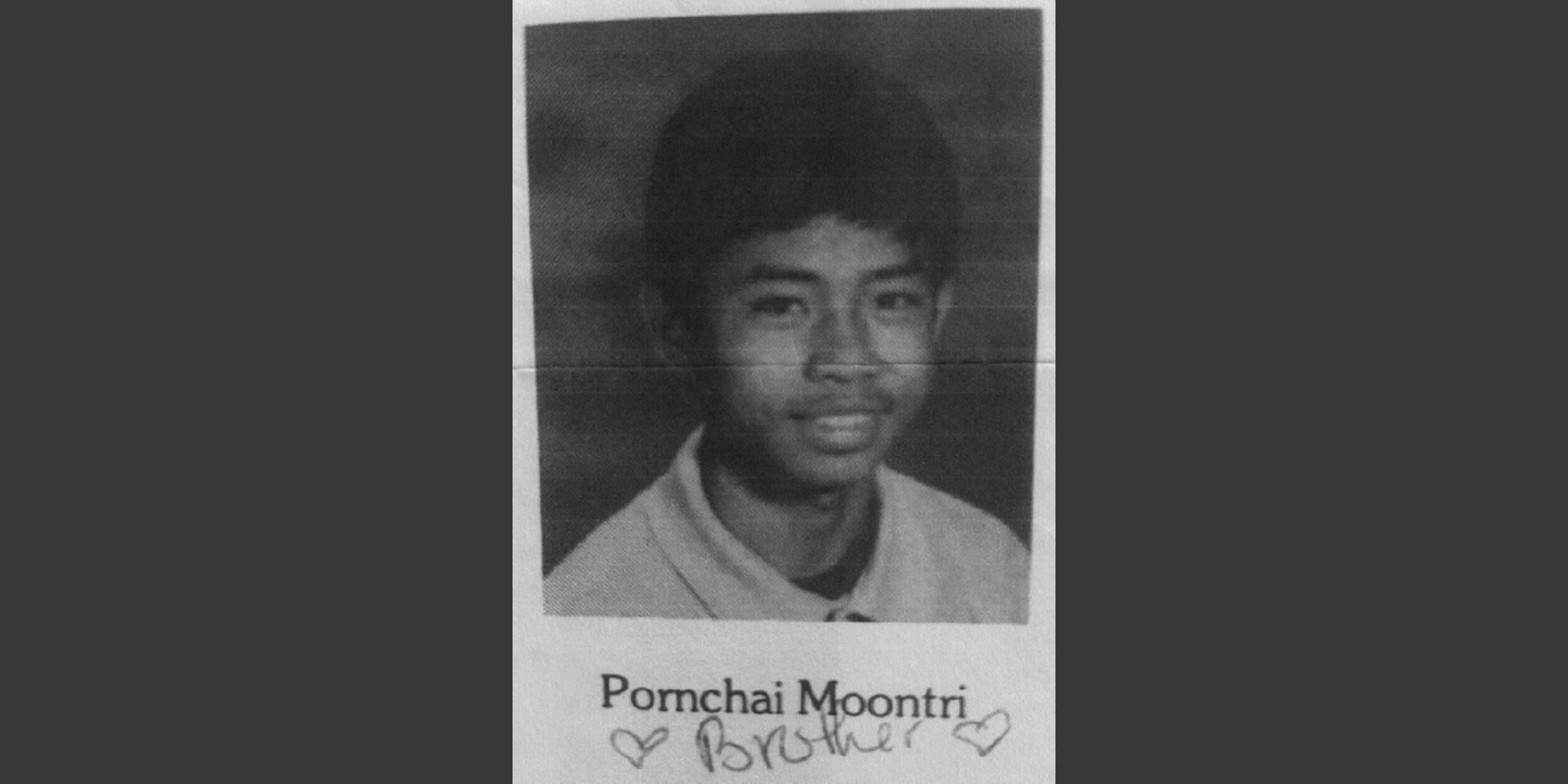

Editor’s note: The photo of Pornchai Moontri at the top of this post was a middle school yearbook photo taken at age 12 just after his arrival in America and just prior to the onset of events described in this post. His brother Priwan wrote the word “Brother” with the two hearts under the photo in the yearbook.

In nine years of writing for Beyond These Stone Walls, this is the most important post I have ever composed. If you have never before shared my posts on social media or emailed them to friends, I urge you to share this one. It is not about me — at least, not directly. It is about something that has haunted my every day for the last twelve years. It’s about someone who committed a ‘real’ and tragic criminal act, but was himself the victim of a horrible crime. It is something so ironic it defies belief.

I recently hinted that this story was coming. After twelve years in the making it came to its apex this month on the Feast of the Most Holy Name of Mary. Here’s what I wrote in a recent post about “Mary, Undoer of Knots”:

“I want to put some unexpected context on the significance of that day — September 10, 1985 — as I eulogized my beloved Uncle near Harvard. Unbeknownst to me, on that same day and moment on the far side of the world, Pornchai Moontri turned 12 years old in Bangkok, Thailand where he was reunited with his mother after her ten-year absence from his life. On that day, he began a journey to a promised new life in America.”

Six-and-a-half years later, on Saturday evening, March 21, 1992, in a state of intoxication, 18-year-old Pornchai Moontri walked into a Bangor, Maine supermarket and tried to walk out with a six-pack of beer. He was chased into the parking lot. In his drunken state Pornchai had trouble piecing together what came next. He heard much of it for the first time sitting in court.

As he fled across the Shop’n Save parking lot that night, 27 year-old Michael Scott McDowell injected himself into the scene. He saw store employees chasing a young Asian man and assumed it was for shoplifting. The much larger McDowell tackled Pornchai and wrestled him to the ground. Pinned down and helpless, Pornchai described this moment in “Pornchai’s Story” as “something that lived in me got out.”

Pornchai remembers getting up and running, running, running. Later that night he wandered the streets alone, exhausted and confused. He lived on those streets, a homeless teenager in a small port city of 31,000 in a foreign country. He slept under a bridge. As he fled, hunted, through the streets of Bangor that night, a car pulled up. A man he neither knew nor remembers told him to get in.

There, in that vehicle, he sat in silence until the police came for him. To this day, he knows nothing of the identity of the man who sheltered him. Pornchai was charged with assault with a deadly weapon, a knife he carried for protection while living on the streets. The next morning, the police told him that the charge is upgraded to murder. Michael Scott McDowell had died.

On Thursday, September 30, 1992, journalist Steve Kloehn penned a report for the Bangor Daily News entitled, “McDowell murder closed with a verdict, not a reason.” Its opening paragraph set the stage for the mystery contained therein:

“Thomas Goodwin, representing the state of Maine, was trying to explain to a jury the inexplicable: how Pornchai Moontri walked into the Shop’n Save a teenager and came out a murderer.”

Until now, I have not been able to write the whole truth of my last twelve years behind these stone walls. I have alluded to some of it in cryptic prose, but not everyone caught it. But many understood that there is an important story coming, a true story of unimaginable pain, power, and consequence. This is the most important post I have ever written.

If you have been reading these pages with any regularity at all, then you have come to know Pornchai “Maximilian” Moontri. This is his story, and it may bring tears. It should. But the sun also rises, and with the long awaited dawn comes — if not rejoicing — then at least a modicum of peace.

Solitary Confinement

Pornchai and I first met at the New Hampshire State Prison in 2006. He had been transferred from a “Supermax” prison in the State of Maine where he served the previous fourteen years — half of them in the utter cruelty of solitary confinement. He had a short fuse. He lived with a despair and a rage that walls could not contain.

The system deemed Pornchai to be dangerous, unfit for the presence of other human beings. A day in his life in Maine’s “supermax” prison was chronicled by the social justice site, “Solitary Watch” in an article entitled, “Welcome to Supermax.” After fourteen years in and out of that horror — including nearly four years in one long grueling stretch — Pornchai was transferred to another state.

The transfer from a prison in Maine to one in New Hampshire was administrative and not at Pornchai’s request. His arrival in 2006 took him to a very familiar place: an initial stay in solitary confinement. After a few months he was sent to a close custody unit, and finally to a unit in the general prison population where he and I met and became friends in early 2007.

I remember the first time we met. I was walking through the prison “chow hall” carrying my tray of food. As I made my way among the crowded tables looking for a seat, I heard my name. “Hey G, sit here with us.” I spotted my young Indonesian friend, Jeclan Wawarunto sitting next to the meanest looking young Asian man I had ever encountered. I could instantly see why the other two seats at their table were still empty.

“Come sit with us,” said the ever-smiling Jeclan. “This is my new friend, Ponch. He just got here.” As I sat down, I looked into the dark eyes of the young man across from me and saw anger, but it was anger masking something else, a hurt and pain I had never imagined possible. “Ponch wants to ask you a question,” said Jeclan. His friend looked so agitated that I looked quickly away. “I just want to know if you can help me transfer to a prison in Bangkok, Thailand,” said Pornchai with hostility.

I had, ironically, just finished reading a book — 4,000 Days — about the horror of life in a Bangkok prison. I told the young man that I would not help him do something that would only destroy him. “Who is this jerk?” he asked Jeclan. Weeks later, I was surprised to see that same young Asian man dragging a trash bag with his belongings into the housing unit where I lived. I approached him and said, “I’m glad you’re here.” He glared at me as though I were crazy.

We slowly became friends. I cannot really explain this long, slow, gradual building of trust with someone for whom trust is a deadly affair. I today know the courage it took for Pornchai to trust me. One day, his assigned cell mate came to me and said that he did not know what to do. He said that Pornchai had not spoken, eaten or even gotten out of bed for days.

I went to see Pornchai. He was known for having a short fuse, but I told him I would not leave until he got out of that bunk and spoke with me. I told him that I know what is under how he feels right now. I asked him to let me try to help him.

Some time later, his cell mate moved. Prison officials were cautious in imposing a new cell mate on Pornchai, so they told him to find someone he wanted to live with. He asked me and I said yes. It was early 2007. Over time, as trust developed, the story of Pornchai’s life was drawn out of him — de profundis — from out of the depths. It is a remarkable account that is now fully corroborated, and it is shocking.

From Thailand to Terror

Pornchai was born on September 10, 1973 near the village of Bua Nong Lamphu in the Northeast of Thailand beyond the city of Khon Kaen. His father was a Thai marshal arts fighter who earned a hard-won living traveling from town to town for bouts. He was sometimes away for long periods. When Pornchai was two years old, and his brother, Priwan, was four, their mother, Wannee, left telling them that she was going to the city. She did not return. The two boys were abandoned and stranded.

Their father came home weeks later to find Pornchai and Priwan foraging for food in the streets. Pornchai was hospitalized for severe malnutrition. When he left the hospital, his father was also gone, leaving them in the custody of another woman. She eventually put them out into the street where again they had to forage for food and shelter.

Learning of this, the extended family of Pornchai’s missing mother sent a 17-year-old uncle to search for the two boys and bring them to their small farm. Pornchai and Priwan grew up there raising rice, sugar cane, and water buffalo. They worked hard, but they were happy. Over time, Pornchai forgot his mother. He came to believe that his Aunt Mae Sin was his mother.

It was 1975 when Wannee left Pornchai and Priwan at ages two and four. She went to Bangkok to find work. While there she met Richard Bailey, an American military veteran and air traffic controller from Bangor, Maine who was a frequent visitor to Thailand. He brought Wannee to the United States.

Nine years passed. In 1985, when Pornchai was 11 years old, his mother, Wannee, suddenly reappeared in Thailand to claim her sons. Pornchai had no memory of her, and was traumatized to be taken away by a stranger. He never saw his home and family again. Wannee took Pornchai and Priwan to Bangkok for several months to await passports and travel documents. Pornchai turned 12 in Bangkok on September 10, 1985. Wannee told Pornchai and his brother that in America, they would never be hungry again.

In early December, 1985, they flew from Bangkok to Boston where Wannee’s husband, Richard Bailey, met them. On the long drive from Boston to Bangor, Pornchai and Priwan had their first meal in America at a McDonalds drive-thru. Both boys vomited the meal out the back seat windows of the car.

From the moment of their arrival in Bangor, the tone changed rapidly. Richard controlled their money, their speech, and their every move. The two boys and their mother were forbidden from speaking Thai in Bailey’s presence, and neither boy spoke or understood English.

Richard Bailey’s sister, who always treated Pornchai and Priwan with kindness, asked them what they wanted for Christmas. The boys did not know much about Christmas, but they understood that it involves presents. Pornchai’s adjustment had been traumatic. He asked for a watch and a teddy bear.

I caution you that from here on, this story may be difficult to read but please be brave for our friend who lived it. That night Pornchai was awakened from sleep and brought to a basement room by Richard Bailey. While there, Pornchai was forcibly raped by Bailey, an event that was to be repeated too many times to count. Pornchai was traumatized and terrified.

He did not understand what was being said, but its meaning was clear. If he resisted or told, the consequences to his mother would be severe. To demonstrate this, Bailey beat Wannee in the presence of both boys. When they tried to stop him, he beat them as well. They were treated as slaves.

Bailey then arranged separate bedrooms for the two brothers. Only much later did Pornchai learn that Bailey also raped his brother Priwan. In fear for each others’ safety, they both kept silent. They lived in a nightmare from which they saw no escape.

Witnesses who grew up in Bangor, and had read of Pornchai at this blog, have come forward with accounts of the 12-year-old who showed up at their homes traumatized, beaten and bloody. One man reports that he confronted Richard Bailey who later beat Pornchai again while forbidding him to interact with neighbors. Others have similar accounts. A school nurse reported his injuries. Nothing happened.

The first police intervention came when Pornchai was 13. He had run away, following railroad tracks out of Bangor. After a day or two, Richard Bailey reported him missing. Sheriff’s deputies pursued Pornchai through the woods and caught him. They did not understand his protests as they handed him back over to Bailey, but they filed a report alluding to their suspicions. Nothing happened.

Lost in America

By the time Pornchai was 14 in 1987, his brother, Priwan, traumatized and broken, fled Bangor. Pornchai was alone. He ran away again and again, and while evading police he lived for months on the streets of Bangor. For the second time in his life, he was forced to forage for food in the street. He also amassed a police record for stealing food, for truancy, and for being a chronic runaway.

At one point, Wannee asked Pornchai why he keeps running away. Pornchai broke down and told her in Thai what Richard Bailey had been doing to him. She warned Pornchai never to speak of this again. She said Bailey would beat her and then send her back to Thailand with no means to support them.

In the summer Pornchai lived in the woods, or under a downtown Bangor bridge (photo above) where his mother would sometimes bring him food. She held a job as a hotel maid arranged by Richard Bailey, but he tightly controlled her earnings. In the winter, Pornchai would sleep in vacant buildings or at times in the homes of friends whose parents’ welcome of him was at times generous but sometimes not. At 15, he was sentenced to reform school, the Maine Youth Center, and became a ward of the state.

While there, social worker Nancy Cochrane built some trust with Pornchai. When she learned of the severity of the physical and sexual violence he suffered, she filed a formal report with the Sheriff’s department. Deputies interviewed Richard Bailey, but no one else. Bailey convinced them that he heroically gave Pornchai a home in America and Pornchai made this whole story up. The deputies dropped the case without questioning Pornchai or his mother or brother or the social worker treating Pornchai.

The Maine Youth Center staff did not drop the matter so easily. They brought it to other authorities. During the investigation, Wannee visited Pornchai at the facility where he was held. She told him that the police questioned Bailey who then sent her to warn Pornchai to withdraw his claims. The implication — the truth of which Pornchai had already witnessed — was that Wannee would face Richard Bailey’s violence.

Fearing for his mother’s safety, Pornchai refused to cooperate further with the investigation. She was his only contact in both worlds, the nightmare he lived in America and the world he left behind in Thailand. He suffered in silence, consuming the injustices visited upon him like a toxin.

For many years, Pornchai believed that his mother chose to protect Bailey over him and Priwan. But at that moment Pornchai came to see that Wannee was as much a victim of Richard Bailey as he was. The evidence for that belief was still looming on the horizon.

State officials did not understand what was behind Pornchai’s silence. He was transferred to the Goodwill Hinckley School in Maine where he met Joe and Karen Corvino, foster parents who, for a brief period, became instrumental in his life. He later lost contact with them. Their tearful reunion with him came twenty years later when they discovered him by discovering this blog.

Pornchai did well at the Hinckley School. He excelled in Math and Soccer, and the Corvinos recognized the special child who had come to them. They considered legal adoption of Pornchai, but were told this would be difficult given that his biological mother still lived in Maine.

One day, at a soccer match with a rival school, a group of players realized that they could not win with Pornchai on the Hinckley team, so they targeted him for harassment. They pushed him, struck him, checked him, and he endured it all. Finally they shouted slurs about his mother. In seconds, all three of the larger boys were on the ground.

Pornchai was expelled from the game. The next day, over the strenuous objections of Joe and Karen Corvino, he was also expelled from the school. Joe and Karen had no choice but to put the 16-year-old alone on a bus to Bangor. They were told that a social worker would be at the other end but there was no one. At 16, Pornchai was again living on the streets. Sleeping in alleys and doorways, he began to carry a knife for protection.

Pornchai went in search of his brother, Priwan, and found him living in an Asian community in Lowell, Massachusetts. But because Pornchai was still a minor, authorities required that he return to Maine. He petitioned to be emancipated from being a ward of the state. At 17, Pornchai’s legal emancipation was processed by a reluctant Maine Youth Center staff.

The Fateful Day and the Loss of All Hope

At age 18, on March 21, 1992, Pornchai became intoxicated and the tragic offense that began this story took place. It was the last day Pornchai knew freedom, but in reality, his freedom had been taken from him six-and-a-half years earlier at age 12.

This is the context, the “why” that journalist Steve Kloehn asked in the Bangor Daily News at the end of Pornchai’s trial in 1992. Once charged, Pornchai was held without bail for months while awaiting trial in the Penobscot County Jail.

He was assigned a public defender. After a month, Wannee came to visit Pornchai once. Again sent by Richard Bailey, she pleaded with him to protect her by saying nothing of his past life. Convinced his mother was in danger, he again became silent, refusing to allow any defense that included an evaluation of his life. Under duress, he refused to participate in his own defense.

Pornchai’s brother, Priwan, told the public defender of the years of traumatic sexual and physical abuse, but Pornchai refused to discuss this and refused to allow the lawyer to raise it. He was never evaluated, and none of what happened to him became part of the court record. The judge mistook Pornchai’s silence for a defiant lack of remorse. Citing that he “had many opportunities in America but squandered them,” she sentenced 18 year-old Pornchai to 45 years in the Maine State Prison.

After the trial, Richard Bailey sold his Bangor home, took Wannee, and purchased land and a home on the U.S. Territorial Island of Guam in the Western Pacific. At age 18, alone and in prison, Pornchai was thousands of miles from his only contact with the outside world.

Eight years passed before he saw his mother again. She traveled to Thailand, and then to Maine to visit Pornchai in prison. She told him she was returning to Guam to finalize her divorce from Richard Bailey and financial settlements in the Guam courts. The year was 2000, Pornchai’s eighth year in prison.

To this day, the financial agreements ordered in the divorce decree have not been met. A cousin of Wannee in Thailand today reports that, upon her return to Guam, Wannee called her in 2000. Richard could be heard shouting in the background. The cousin states that Wannee cried that she is being threatened, and if she is found dead, she wants her cousin to demand an investigation.

Weeks later, Pornchai learned in prison that his mother had been murdered on the Island of Guam. He could learn no details except that it was filed as a homicide. The autopsy report indicates that she had been beaten to death and her body left on a beach. A Guam police report shows that Richard Bailey reported her missing, then the next day reported finding her body himself. No one has been charged. It remains today a “cold case” unsolved homicide in Guam.

This was a breaking point for Pornchai. He gave up, and ended up spending the next nearly seven years in and out of solitary confinement in Maine’s supermax prison. After seven years in hell, Pornchai was transferred to the New Hampshire State prison where we met. You know most of what followed, but not all. [Editor: WGBH-PBS Frontline’s documentary “Locked Up in America – Solitary Nation” depicts the nightmare of Pornchai’s solitary confinement. The prisoners you see were in solitary with him in adjacent cells. We’ve been having problems with the link, but this one to WGBH works well Frontline Solitary Nation.]

Once I learned the entire story, I could not let it go. I began several years ago to make discreet inquiries into Pornchai’s life in both Thailand and Maine. In 2007, shortly after we became friends and cell mates, a U.S. Immigration judge ordered that Pornchai is to be deported from the United States upon completion of his sentence. I assisted him in an appeal based on the severity of his life and his need for asylum, but to no avail.

I told Pornchai that we will need to build some connections in Thailand. He said that he did not even know where to begin. Pornchai felt overwhelmed, and took refuge in his imagined “Plan B” — his own final self-destruction. I challenged him to trust. A few years later, on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010, Pornchai became a Catholic, and accepted my challenge to place his future in God’s hands with the guidance of his chosen Patron Saint, Maximilian Kolbe, whose name Pornchai chose as his own.

Then, Felix Carroll and Marian Press published Loved, Lost, Found with a beautiful chapter about Pornchai’s conversion. Felix graciously made the chapter available for posting. It made its way to Thailand where it moved many people in Bangkok to become involved in Pornchai’s story. A group called “Divine Mercy Thailand” organized to help bring him home. They have assured him of a home and support system when he returns.

Richard Alan Bailey at the time of his arrest on forty counts of felonious sexual assault.

A Day in Court

After being received into the Church, I convinced Pornchai to seek some treatment in the prison system. He was diagnosed with acute anxiety and severe Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He is working with a counselor and is prescribed a medication for acute anxiety and another to inhibit nightmares.

The inquiries I had been making produced some amazing results. Clare and Malcolm Farr, a husband/wife team from an intellectual property law firm in Perth, Australia had been reading Beyond These Stone Walls. Entirely pro bono, they immersed themselves in Pornchai’s story with overtures to the government of Thailand and the State of Maine. Clare Farr, one of the attorneys, has been in daily contact with us over the last three years.

Their tireless efforts gained the notice of the Thai Consulate in New York from where officials have since visited Pornchai and involved themselves in his plight. This story also gained the attention of law enforcement in the State of Maine from where an investigation was launched. Detectives from the Bangor police traveled to Concord, NH to interview Pornchai and also met with his brother, Priwan. An Assistant District Attorney came on the second interview.

In 2017, Richard Alan Bailey was indicted on forty felony counts of gross sexual misconduct for his well documented victimization of Pornchai and his brother. He was arrested at his West Lake, Oregon home and released on $49,000 cash bond. On September 12, 2018, the Feast of the Most Holy Name of Mary, Richard Bailey entered a plea of no contest but was found guilty and stands convicted of the charges. At this writing, the 2000 Guam case remains an open unsolved homicide.

Bailey’s sentence may bring the biggest gasp of all, forty-four years in prison, but all suspended, and eighteen years of supervised probation. He will not serve a day in prison. This was a hard truth for me. I am serving 67 years in prison for crimes that never took place, with a fraction of the charges faced by Richard Bailey and with none of the evidence. It is clear. He is not ‘Father’ Richard Bailey.

Covering this story for the Bangor Daily News, reporter Judy Harrison referred to Pornchai as “the now 45-year-old convicted killer.” Fully one third of her brief coverage of this story focused not on Richard Bailey’s crimes, but on Pornchai’s. Judy Harrison turned a deaf ear to the profoundly troubling serial victimization that his Victim Impact Statement describes.

The shallowness of reporters notwithstanding, Pornchai has also learned the ways of Divine Mercy. He learned them from me. In his submitted impact statement, he asked the court for justice but also for mercy for his tormentor, the very person who has haunted his nightmares for all these years. From Pornchai’s Victim Impact Statement presented in court:

“My brother has struggled with gambling and alcohol addictions and my mother is dead. Richard carried out more sexual assaults against me than there are current charges against him. His actions have robbed me of a normal life which I can never reclaim. Fortunately I have since had a lot of counseling and with the guidance of a wonderful Catholic priest I have found faith and a firm belief in God… I asked God to help me to forgive Richard and through my strong faith I have done this… I cannot forget what he has done but I do forgive him. The law must pass a just sentence, but I agree with the terms of this plea agreement.”

But there is something even more compelling in this story. Pornchai Moontri came to me, a Catholic priest whom he believes with all his heart to be innocent of the very things that stole his hope and his ability to trust. The irony sends me to my knees in thanksgiving for an opportunity. The most important mission of my life as a man and as a priest has been walking with Pornchai Moontri from dusk to dawn in his survival of the darkest night.

Editor’s Note: Thank you for reading and sharing this important post. You may also like these related posts:

Getting Away with Murder on the Island of Guam by Fr Gordon MacRae

Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom by Fr Gordon MacRae

Elephants and Men and Tragedy in Thailand by Pornchai Maximilian Moontri

What do John Wayne and Pornchai Moontri Have In Common?

As Advent begins in the midst of some long-awaited changes and revisions in the Catholic Mass, I have been doing some thinking about the nature of change.

As Advent begins in the midst of some long-awaited changes and revisions in the Catholic Mass, I have been doing some thinking about the nature of change.

In “February Tales,” an early post at Beyond These Stone Walls, I described growing up on the Massachusetts North Shore — the stretch of seacoast just north of Boston. My family had a long tradition of being “Sacrament Catholics.”

I once heard my father joke that he would enter a church only twice in his lifetime, and would be carried both times. I was seven years old, squirming into a hand-me-down white suit for my First Communion when I first heard that excuse for staying home. I didn’t catch on right away that my father was referring to his Baptism and his funeral. I pictured him, a very large man, slung over my mother’s shoulder on his way into church for Sunday Mass, and I laughed.

We were the most nominal of Catholics. Prior to my First Communion at age seven, I was last in a Catholic church at age five for the priesthood ordination of my uncle, the late Father George W. MacRae, a Jesuit and renowned Scripture scholar. My father and “Uncle Winsor,” as we called him, were brothers — just two years apart in age but light years apart in their experience of faith. I was often bewildered, as a boy, at this vast difference between the two brothers.

But my father’s blustering about his abstention from faith eventually collapsed under the weight of his own cross. It was a cross that was partly borne by me as well, and carried in equal measure by every member of my family. By the time I was ten — at the very start of that decade of social upheaval, life in our home had disintegrated. My father’s alcoholism raged beyond control, nearly destroying him and the very bonds of our family. We became children of the city streets as home and family faded away.

I have no doubt that many readers can relate to the story of a home torn asunder by alcoholism, and some day soon I plan to write much more about this cross. But for now I want to write about conversion, so I’ll skip ahead.

The Long and Winding Road Home

As a young teenager, I had a friend whose family attended a small Methodist church. I stayed with them from time to time. They knew I was estranged from my Catholic faith and Church, so one Sunday morning they invited me to theirs. As I sat through the Methodist service, I just felt empty inside. There was something crucial missing. So a week later, I attended Catholic Mass — secretly and alone — with a sense that I was making up for some vague betrayal. At some point sitting in this Mass alone at age 15, I discovered that I was home.

My father wasn’t far behind me. Two years later, when just about everyone we knew had given up any hope for him, my father underwent a radical conversion that changed his very core. He admitted himself to a treatment program, climbed the steep and arduous mountain of recovery, and became our father again after a long, turbulent absence. A high school dropout and machine shop laborer, my father’s transformation was miraculous. He went back to school, completed a college degree, earned his masters degree in social work, and became instrumental in transforming the lives of many other broken men. He also embraced his Catholic faith with love and devotion, and it embraced him in return. That, of course, is all a much longer story for another day.

My father died suddenly at the age of 52 just a few months after my ordination to priesthood in 1982. I remember laying on the floor during the Litany of the Saints at my ordination as I described in “Going My Way,” a Lenten post last year. I was conscious that my father stood on the aisle just a few feet away, and I was struck by the nature of the man whose impact on my life had so miraculously changed. Underneath the millstones of addiction and despair that once plagued him was a singular power that trumped all. It was the sheer courage necessary to be open to the grace of conversion and radical change. The most formative years of my young adulthood and priesthood were spent as a witness to the immensity of that courage. In time, I grew far less scarred by my father’s road to perdition, and far more inspired by his arduous and dogged pursuit of the road back. I have seen other such miracles, and learned long ago to never give up hope for another human being.

The Conversion of the Duke

A year ago this very week, I wrote “Holidays in the Hoosegow: Thanksgiving With Some Not-So-Just Desserts.” In that post, I mentioned that John Wayne is one of my life-long movie heroes and a man I have long admired. But all that I really ever knew of him was through the roles he played in great westerns like “The Searchers,” “The Comancheros,” “Rio Bravo,” and my all-time favorite historical war epic, “The Longest Day.”

In his lifetime, John Wayne was awarded three Oscars and the Congressional Gold Medal. After his death from cancer in 1979, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But, for me, the most monumental and courageous of all of John Wayne’s achievements was his 1978 conversion to the Catholic faith.

Not many in Hollywood escape the life it promotes, and John Wayne was no exception. The best part of this story is that it was first told by Father Matthew Muñoz, a priest of the Diocese of Orange, California, and John Wayne’s grandson.

Early in his film career in 1933, John Wayne married Josephine Saenz, a devout Catholic who had an enormous influence on his life. They gave birth to four children, the youngest of whom, Melinda, was the mother of Father Matthew Muñoz. John Wayne and Josephine Saenz civilly divorced in 1945 as Hollywood absorbed more and more of the life and values of its denizens.

But Josephine never ceased to pray for John Wayne and his conversion, and she never married again until after his death. In 1978, a year before John Wayne died, her prayer was answered and he was received into the Catholic Church. His conversion came late in his life, but John Wayne stood before Hollywood and declared that the secular Hollywood portrayal of the Catholic Church and faith is a lie, and the truth is to be found in conversion.

That conversion had many repercussions. Not least among them was the depth to which it inspired John Wayne’s 14-year old grandson, Matthew, who today presents the story of his grandfather’s conversion as one of the proudest events of his life and the beginning of his vocation as a priest.

If John Wayne had lived to see what his conversion inspired, I imagine that he, too, would have stood on the aisle, a monument to the courage of conversion, as Matthew lay prostrate on the Cathedral floor praying the Litany of the Saints at priesthood ordination. The courage of conversion is John Wayne’s most enduring legacy.

Pornchai Moontri Takes a Road Less Traveled

The Japanese Catholic novelist, Shusaku Endo, wrote a novel entitled Silence (Monumenta Nipponica, 1969), a devastating historical account of the cost of discipleship. It’s a story of 17th Century Catholic priests who faced torture and torment for spreading the Gospel in Japan. The great Catholic writer, Graham Greene, wrote that Silence is “in my opinion, one of the finest novels of our time.”

Silence is the story of Father Sebastian Rodriguez, one of those priests, and the story is told through a series of his letters. Perhaps the most troubling part of the book was the courage of Father Rodriguez, a courage difficult to relate to in our world. Because of the fear of capture and torture, and the martyrdom of every priest who went before him, Father Rodriguez had to arrive in Japan for the first time by rowing a small boat alone in the pitch blackness of night from the comfort and safety of a Spanish ship to an isolated Japanese beach in 1638 — just 18 years after the Puritan Pilgrims landed the Mayflower at Squanto’s Pawtuxet, half a world away as I describe in “The True Story of Thanksgiving.”

In Japan, however, Father Rodriguez was a pilgrim alone. Choosing to be left on a Japanese beach in the middle of the night, he had no idea where he was, where he would go, or how he would survive. He had only the clothes on his back, and a small traveler’s pouch containing food for a day. I cannot fathom such courage. I don’t know that I could match it if it came down to it.

But I witness it every single day. Most of our readers are very familiar with “Pornchai’s Story,” and with his conversion to Catholicism on Divine Mercy Sunday in 2010. Most know the struggles and special challenges he has faced as I wrote in “Pornchai Moontri, Bangkok to Bangor, Survivor of the Night.”

But the greatest challenge of Pornchai’s life is yet to come. In two years he will have served twenty-two years in prison — more than half his life, and half the original sentence of forty-five years imposed when he was 18 years old. In two years time, if many elements fall into place and he can find legal counsel, Pornchai will have an opportunity to seek some commutation of his remaining sentence based on rehabilitation and other factors.

It is a sort of Catch-22, however. Pornchai could then see freedom at the age of forty for the first time since he was a teen, but it will require entering a world entirely foreign to him. On the day Pornchai leaves prison — whether it is in two years or ten or twenty — he will be immediately taken into custody under the authority of Homeland Security and the Patriot Act, flown to Bangkok, Thailand, and left there alone. It is a daunting, sometimes very frightening future, and I am a witness to the anxiety it evokes.

For every long term prisoner, there comes a point in which prison itself is the known world and freedom is a foreign land. Pornchai has spent more than half his life in prison.

Even I, after seventeen years here, sometimes find myself at the tipping point, that precipice in which a prisoner cannot readily define which feels more like the undiscovered country — remaining in prison or trying to be free. I had a dream one night in which I had won my freedom, but entered a hostile world and Church in which I was a pariah, living alone and homeless in a rented room in hiding, pursued by mobs of angry Catholics. I know well the anxious fears of all the prisons of men.

Pornchai was brought to the United States against his will at the age of eleven. That story is told in deeply moving prose by Pornchai himself in “Pornchai’s Story.” I think we became friends because by the strangeness of grace I knew only too well the experience of having the very foundations of life and family and all security fall out from under me. Pornchai spoke a language that I understood clearly. The transformation of pain and sorrow into the experience of grace is the realm of God, and enduring it to one day lead another out of darkness is a great gift. In the end, who can ever say what is good and what is bad? It is not suffering that is our problem, but rather what we do with it when it finds us.

But what Pornchai faces in the future is daunting. With no opportunity for schooling as an abandoned child in Thailand, he never learned to read and write in Thai and hasn’t heard the Thai language spoken since he was eleven. He remembers little of Thai culture, has no prospects to support himself, no home there, no contacts, and no solace at all. Like Father Rodriguez in Silence, Pornchai will be dropped off in a foreign country, and left to fend for himself with no preparation at all beyond what he can scrape up from behind prison walls in another continent. Welcome to the new America!

Pornchai’s options are limited. He can try to bring about this trauma sooner by seeking commutation of his sentence at an age at which he may still somehow build a life in Thailand. Or he can remain quietly in prison another decade or more, postponing this transition until he is much older, with fewer chances for employment, but perhaps can find connections in Thailand.

These are not great choices. “Pornchai’s Story” got the attention of the Thai government and the Cardinal Archbishop of Bangkok two years ago, but the Thai government has been in chaos since, and the Archbishop has retired. All overtures to both since 2009 have been met by silence.

So in the midst of all this dismal foreboding, and in the face of a future entirely unknown, and perhaps even bleak, Pornchai Moontri became a Catholic. He embraced a faith practiced by less than one percent of the people who will one day be his countrymen again, and in so doing, he piled alienation upon alienation.

And yet this man who has no earthly reason to trust anything to fate, trusts faith itself. I have never met a man more determined to live the faith he has professed than Pornchai Moontri. In the darkness and aloneness of a prison cell night after night for the last two of his twenty years in prison, Pornchai stares down the anxiety of uncertainty, struggles for reasons to believe, and finds them.

I am at a loss for more concrete sources of hope for Pornchai. But like Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman, whom I have quoted so often, I believe that “I am a link in a chain; a bond of connection between persons.”

Someone out there holds good news for Pornchai — something he can cling to in hope. I await it with as much patience as I can summon. Pornchai awaits it with a singular courage — the courage of conversion that seeks the spring of hope in the winter of despair.