“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Canon Law Conundrum: When Moral Certainty Is Neither Moral Nor Certain

Convoluted moral justification is employed by Jesuits of the USA Central and Southern Province to publish a list of priests with ‘credible’ allegations of abuse.

The Stoning of Saint Stephen by Rembrandt

Convoluted moral justification is employed by Jesuits of the USA Central and Southern Province to publish a list of priests with ‘credible’ allegations of abuse.

May 3, 2023 by Michael J. Mazza, JD, JCD

Introduction by Fr. Gordon MacRae: It is an honor and a privilege to publish this important guest post by Michael J. Mazza, JD, JCD, (pictured below at the Vatican) a highly regarded canon lawyer, civil attorney, and law professor with broad experience in the canonical defense of Catholic priests. His post is a sequel of sorts to my post in these pages last week, “Follow the Money: Another Sinister Grand Jury Report.” His post introduces us to a newly articulated standard for removing priests from ministry adopted by a Jesuit Province in the United States. It is a standard that left me shuddering over the rapid decline of due process rights for priests. Like other such draconian standards, I fear its use will spread like a virus.

Back in August, 2019, Ryan A. MacDonald wrote a featured post for Beyond These Stone Walls entitled “In the Diocese of Manchester, Transparency and a Hit List.” It has been one of our most widely read posts of recent years and continues to be so. Ryan wrote about the injustice of publishing names of accused priests when the basis for deeming a claim to be ‘credible’ is a standard of justice not employed or even recognized in any other legal forum. It essentially means that an allegation of abuse is only “possible,” but not necessarily “probable.” It should be the beginning of a Church investigation, but it has widely become the end.

This is a standard that is now employed by nearly every bishop in every diocese, and it is rapidly spreading throughout the Church. Michael Mazza’s post to follow understandably has a bit more ‘legalese’ than usually comes from my typewriter, but it is a brilliant eye-opener.

There was a smoldering cloud just above my head as I three times read the Jesuits’ confounding justification for censuring and removing priests. In a word, it is mind-boggling.

This post shines a much needed light on the need for canonical justice and advocacy for accused priests. It is highly recommended to us by Fr. Stuart MacDonald, a frequent Beyond These Stone Walls contributor and a candidate for the Doctorate in Canon Law. Please share this post widely, especially among the priests you know.

When Moral Certainty Is Neither Moral Nor Certain

Two months ago the Jesuits USA Central and Southern Province released an updated registry of Jesuits with “credible allegations of sexual abuse of a minor.” As a canonical advocate representing priests accused of misconduct, I was involved in one of the cases referenced. Given the requirements of canon law and my professional duties, I am limited in what I can say about the case. What I can discuss — in fact, what I feel I must rectify — is the grievous error of law contained in the Jesuit Province’s published statement, a mistake that despite my best efforts has gravely damaged the reputation of a good priest and respect for the rule of law in the Church.

The most problematic part of the statement appears in its first paragraph:

“For the purposes of this list, a finding of credibility of an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor is based on a belief, with moral certitude, after careful investigation and review by professionals, that an incident of sexual abuse of a minor or vulnerable adult occurred, or probably occurred, with the possibility that it did not occur being highly unlikely. ‘Moral certitude’ in this context means a high degree of probability, but short of absolute certainty. As such, inclusion on this list does not imply the allegations are true and correct or that the accused individual has been found guilty of a crime or liable for civil claims.”

It is difficult to know where to begin with an analysis of this confounding passage. Did the event happen or not? We are told on the one hand that being included on the list “does not imply the allegations are true and correct.” At the same time, however, we are told that “after careful investigation” and “review by professionals,” the allegation has been determined “with moral certitude” to have “occurred or probably occurred.” In fact, the statement says the possibility that the events did not occur “is highly unlikely.”

While such a confusing statement may appear to have been crafted by two opposing camps of a drafting committee, the real world consequences of it were clear, especially because it was accompanied by the usual invitation for victims of abuse to come forward. The news was reported as a “shock” to the students at the university where the priest had been a popular professor, leaving some brokenhearted and in tears. A theology professor said the news had “shaken” him and his colleagues, with one priest colleague concluding thus: “It’s mind-boggling that anyone would do such a thing, period end of story.”

Conclusions like these are not surprising. What is surprising — and what ought to be profoundly disturbing to those who value the rule of law — is that they have no legal basis whatsoever. Like so many of his priestly brethren in the USA accused of canonical crimes these days, the priest at issue was never given the benefit of a trial during which he could have defended his innocence. Instead, the priest was on the receiving end of what is known in canon law as a “preliminary investigation,” a technique under canon 1718 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law that is designed solely to determine whether there is sufficient indicia to warrant the launching of a full-blown canonical process. Only after this formal process, whether judicial or administrative, may a penalty be inflicted or declared. And it is only through this formal process that “moral certainty” — the canonical equivalent of “beyond a reasonable doubt” — may be achieved under the law.

An analogy may prove helpful here. Suppose that Mary, a juror in a domestic abuse trial, learns of allegations that John abused Jane. Mary hears from Jane, the only witness at the trial, about the details of her charge. Mary knows only that John denies the accusation, but does not hear from him because John is not present at the trial. In fact, neither John nor his defense counsel is even invited to the trial. If Mary nevertheless arrives at John’s guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt,” in spite of the fact that John was not allowed to exercise his natural human right to self-defense, what would we say about Mary’s judgment?

All analogies limp, and several objections could immediately be raised with respect to this one. Just because there were no other witnesses does not mean that there was no abuse, a sin and a crime that is horrible and was often covered up in the past, especially in ecclesial circles. While these statements are certainly true, summarily dismissing valid concerns about violations of the due process rights of accused clerics is not a solution to the sex abuse crisis. On the contrary, it only perpetuates a continuing injustice and creates an atmosphere of fear, mistrust, and division within the ecclesial community. That is not a sustainable path forward.

It needs to be emphasized that a canonical preliminary investigation is typically performed by an individual (most often but not always a former law enforcement official) whose only job is to assemble indicia substantiating an allegation. The investigator then presents these indicia to a review board, generally constituted by lay people (at least some of whom are to have experience in law or psychology), who make a recommendation to the religious superior or bishop about whether a full-blown canonical investigation should be initiated.

In some ways, the work of a review board is similar to that of a grand jury. Grand juries, like review boards, are supposed to act as shields against arbitrary, unfounded, and malicious accusations of wrongdoing by ensuring that serious accusations are brought only upon the considered judgment of a representative body acting according to the rule of law. Grand juries, like review boards, do not decide whether the accused is guilty; they merely decide whether there is probable cause to believe that a crime occurred and probable cause to believe that the person accused committed that crime. In short, grand juries, like review boards, decide only whether there is enough evidence to proceed to the next stage in the judicial process.

This is because of the deliberately one-sided nature of grand jury proceedings. Only the prosecutor — not the defense — gets to address the grand jury. All of the important safeguards of justice are saved for the real trial that comes only after the grand jury has performed its important task. Nevertheless, all this means that in a very real way the life and reputation of a fellow citizen are in the hands of the grand jurors. Indictments, like recommendations from review boards, often receive press coverage in which these legal niceties are overlooked, meaning that the reputation of the person accused is harmed and his life thrown into turmoil.

Many accused priests never get a trial, “period end of story.” Nevertheless, their lives are thrown into turmoil, beyond any doubt. What do we make of subsequent decisions by accused clerics to abandon the fight, or to leave religious life and/or the active priesthood? One could certainly infer guilt from it, and many people do just that. But isn’t it also possible that there are other reasons for such momentous decisions? With no forum to clear their names, and in spite of repeated and consistent denials of the charge — and the lack of any criminal proceedings or any record from a related civil trial — isn’t it at least possible that some clerics simply despair of ever clearing their names and just decide to move on with their lives as best they can?

Catholics should be very wary of making judgments about their fellow human beings. We have been cautioned against it by Our Lord himself (see, e.g., Mt. 7:1-3). In fact, as legal scholar James Q. Whitman has shown in his 2016 book The Origins of Reasonable Doubt, the original basis for the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard was to encourage reluctant jurors to reach guilty verdicts when the evidence pointed strongly in that direction. Why were they reluctant? Because they feared judging their neighbors, both because of the possible vengeance of the guilty person’s relatives in this world and because of their belief in being judged in the next world.

None of what has been stated in this article is unknown to the American bishops — or, even more importantly, to their lawyers. In fact, in November 2000 the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops issued an insightful commentary on the American criminal justice system entitled “Responsibility, Rehabilitation, and Restoration: A Catholic Perspective on Crime and Criminal Justice.” That statement, as of this writing, is still available on the USCCB website. Issued less than two years before the Dallas Charter, the document criticizes notions such as “zero tolerance” and “simplistic solutions such as ‘three strikes and you’re out,’” with the latter being labelled specifically as a “slogan of the moment.” The paper goes on to quite rightly assert that “crime, corrections, and the search for real community require far more than the policy clichés of conservatives and liberals.”

Notwithstanding such statements, real harm is happening to real men on a daily basis in this country in the name of “transparency.” Perhaps few priests in America know the pain that such sloganeering can inflict as Father Gordon MacRae. Incarcerated for almost three decades after a trial described as “Kafkaesque” by Fr. Richard John Neuhaus. Fr. MacRae not only steadfastly maintains his innocence, but from his prison cell faithfully maintains his website “BeyondTheseStoneWalls.com,” dedicated to drawing attention to the plight of his brother priests and the dangers wrought by violations of the right to due process. MacRae’s case stands as an especially stark example of how pre-trial public statements from his diocese prejudiced his cause, defamed him, and likely helped lead to his wrongful conviction.

In summary, it is essential to note that judging cases involving allegations of child sexual abuse is an enormously painful and difficult process for all involved: the accuser, the accused, and all those involved in the case. Decisions one way or the other can be life-altering. They are not made any easier by those who comment upon them without a firm understanding of both the facts and the applicable law. While legal processes do not come with a guarantee of infallibility, they are a time-tested tool used throughout the centuries for the determination of facts. Legal principles such as moral certainty, the presumption of innocence, and the duty to refrain from unfairly violating someone’s right to a good name are, likewise, bedrock principles of any society. We neglect these valuable tools at our peril.

+ + +

About the Author: Michael J. Mazza, JD, JCD graduated summa cum laude in 1999 from Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee where he was Editor in Chief of the Law Review. He subsequently clerked for the Hon. John L. Coffey on the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago. After 20 years in civil law practice, Michael began studies in canon law at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome from where he graduated magna cum laude in 2021 with a license in canon law (JCL)

In 2022, Michael successfully defended his thesis for the Doctorate in Canon Law (JCD). His topic was also the topic of an excellent article published in the Tulsa Law Review: “Defending a Cleric’s Right to Reputation and the Sexual Abuse Scandal in the Catholic Church.”

Michael is today an adjunct professor of canon law at Marquette University and at Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology outside of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He also represents clients in need of canonical counsel, especially accused priests. If any priest needs canonical assistance Michael can be reached through his website at www.CanonicalAdvocacy.com or by email at mjmazzajdjcd@pm.me.

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: I am most grateful to Professor Mazza for this alarming but important chapter in the cause of justice and due process for priests. You may also like to read and share these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls :

Follow the Money: Another Sinister Sex Abuse Grand Jury Report by Fr. Gordon J. MacRae

Bishops, Priests and Weapons of Mass Destruction by Fr. Stuart MacDonald, JCL

In the Diocese of Manchester, Transparency and a Hit List by Ryan A. MacDonald

Priests in Crisis: The Catholic University of America Study by Fr. Gordon J. MacRae

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Holy Orders in an Unholy Collision with a Disposable Culture

Dealing with the sex abuse crisis has led many bishops to now treat priests as disposable for any infraction resulting in a serious erosion of Catholic theology.

Dealing with the sex abuse crisis has led many bishops to now treat priests as disposable for any infraction resulting in a serious erosion of Catholic theology.

February 1, 2023 by Father Stuart MacDonald, JCL

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: A few weeks ago in these pages I published, “Priests in Crisis: The Catholic University of America Study.” Because it was highly recommended to the huge membership of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, it was one of our most read posts of the year. I then invited Father Stuart MacDonald, JCL, a priest and canon lawyer who serves as advisor to this blog to present a guest post analyzing the same topic and its importance to the Church. Father Stuart’s last post here was “Bishops, Priests and Weapons of Mass Destruction.”

+ + +

I finally went, reluctantly, to a performance of the musical Hamilton. Neither American history nor rap are my particular interests; however, a friend convinced me to go. I am unqualified to offer any observations on the theatrical performance; however, I was indignant at the final message of the show and the audience reaction to it. In a nutshell, if you haven’t seen it, Hamilton is the story of Alexander Hamilton, a founding father of the United States of America and the author of a large number of the Federalist Papers. He was perhaps the first American politician to become involved in a public sex scandal involving marital infidelity. The musical suggests that history has been unkind to Hamilton and that his infidelity played a role in this. It concludes with a rousing song about one’s reputation and posterity. In other words, Hamilton was a great guy and how silly of us to judge his whole career by a single moral failing.

I could not agree more. But let’s face it, the hypocrisy of modern, woke, me-too movement aficionados rapturously cheering this message is comical. In less than a decade, North American culture has accepted as unquestionable the notion that it is unacceptable for leaders of any kind to have lapses in judgment or moral failings. When they do, in the current me-too mindset, they deserve to be cancelled, obliterated from history, never to be seen, heard from, or discussed again except, I realize, when it comes to Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton, the play, is a huge success being performed in several places throughout the world. Does no one else see the hypocrisy? Do people not think anymore? (No, don’t answer that question yet.)

Most readers are aware of the National Study of Priests conducted by The Catholic Project at the Catholic University of America. Father Gordon MacRae wrote of it with his usual aplomb in the link atop this post. What some of you may not have seen is an equally worthwhile analysis of it in Catholic World Report, entitled, “The National Survey of Priests Suggests a Deep Crisis in Catholic Theology,” by Msgr. Thomas Guarino. Father MacRae and I both highly recommend it and we will link to it again at the end of this post.

The import of the study, and the two articles linked above, is the fact that priests, not just in the United States to which all of the above-noted articles are limited, are suffering from a fear of the modern, woke, me-too movement aficionados who seem to be as prevalent in the Church as they are in the world. I do not need to reiterate the scenario of a priest being accused, removed from ministry and either being dismissed from the clerical state or left in limbo on so-called administrative leave. In cases too many to count, priests are abandoned, having been prohibited from exercising any priestly ministry, save the celebration of Mass in private.

Let me be clear, I am not referring to priests accused of sexual abuse of a minor. While the scourge of the sexual abuse crisis is going to be with us for a long time yet, the unfortunate and concomitant truth is that priests are now sitting ducks for any type of accusation. It is specifically to the other stuff that I am referring. Dealing with the sex abuse crisis, however, has led many bishops and Church leaders to think that priests are now like chattel, pieces of property who can be used or discarded at will. The praxis in the Church these days is that a priest can act as a priest only with the explicit permission of his bishop or superior. To put it another way, it is as if a priest is ordained and receives the sacrament of Holy Orders, but the power of those orders is like a tap is turned on or off by the bishop.

Perhaps Father has fallen into sin with a woman, someone doesn’t like Father’s preaching, or maybe Father is insisting on his right to offer Mass ad orientem, or, Heaven forbid, Father uses vulgar language in a fit of anger or impatience (pace the news reports, if indeed true, of Pope Francis’ recent tirade with seminarians from Barcelona). Any of those things, to name just a few, can lead to a priest’s removal from ministry cast into a form of canonical limbo with no defense and from which he may never emerge. The idea seems to have taken over the collective episcopal mindset that a priest exercises his Sacred Orders at his bishop’s unfettered discretion. As Father Thomas Guarino points out so well in his article at the end of this post, this has serious consequences for the Catholic theology of priesthood.

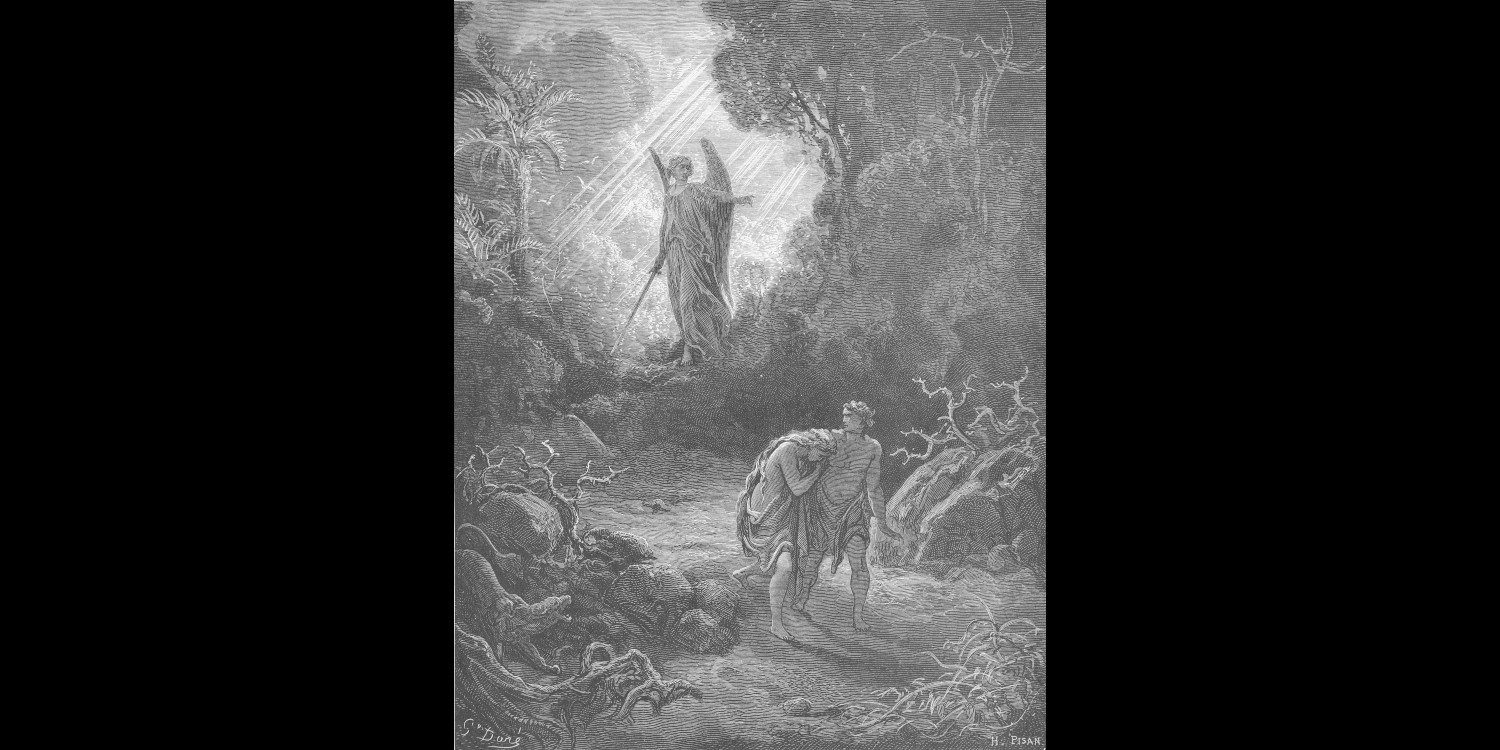

The Expulsion from Eden by Gustave Doré

Catholic Crime and Punishment

Of course, the Church and bishops need to maintain discipline and authority among clergy and religious. No one questions that. But one does rightly question the overreach of control that has crept into our day to day living. Not every bad behavior, or even sinful behavior of a priest is an ecclesiastical crime for which he can be punished or even destroyed. Clearly, if a priest violates his promise of celibacy by sexual acts with an adult woman who is not his parishioner, he commits a mortal sin for which he must repent and do penance like all other sinners. But the Church does not say he has committed a crime. A crime exists, in these specific circumstances, only if he begins to live with her in a married fashion (it doesn’t mean he literally has to live in the same house with her). That is the sin and crime of concubinage.

The last punishment meted out to a priest guilty of that crime is dismissal from the clerical state. It is not the automatic penalty. Clearly, the mind of the Church is that clerics are capable of very serious sin, and the greater is their fall when that happens; but it is naïve to think that clerics are not going to sin, or that some clerics will never commit sexual sins. There is a reason why the Church has had laws against such behavior from the earliest days of her existence.

So, what is happening today? The public backlash from the sexual abuse crisis has placed bishops and religious superiors on edge. No one likes to be unpopular. In an effort to re-instill confidence that the Church is no longer turning a blind eye to the nefarious actions of some clergy with minors, bishops are just appearing ‘tough on crime’ in general. Therefore, anything that a priest does which might reach the ears of the bishop is now fodder for tough disciplinary action. Notice the change in terminology. It is not crime, which would involve inflicting penalties (like suspension, excommunication) using penal law and processes (like criminal law, trials, and sentencing in the civil sphere). Rather, it is disciplinary action for behavior that is not a crime.

The priest who has grievously sinned with a woman, and who has repented of his sin which remains unknown to the public, is now removed as pastor, has had his faculties for preaching and confessions revoked, is forbidden from celebrating Mass in public, and cannot present himself as a priest. All of that for something that is not a crime. No one would tolerate that in the civil sphere. Let me remind you, as Father MacRae has written elsewhere that Saint Padre Pio was falsely accused of all these things and spent years under the unjust cloud of suspicion.

Analogies always fail in some way, I realize, but imagine that you are a manager of a large store of a famous brand name and your supervisor finds out that you committed perjury in court over a traffic accident. Would the supervisor be justified in terminating your employment over actions which did not directly encompass your work duties? Does the priest deserve reprimand? Yes. Should he be advised that any future fall will constitute a crime for which he will be punished? Certainly. Does he deserve immediate dismissal? I don’t think so, no more than the store manager deserves to be punished by his employer. Does his dishonesty raise a red flag about his integrity? Yes. Should his supervisor monitor dishonesty in the workplace? Yes. But it is difficult to imagine that he should be terminated. When priests are terminated or cancelled in this way, the Sacrament of Holy Orders is much diminished, reduced to mere employment from which a priest can be discarded.

It is precisely this situation that has caused the angst so prevalent among priests as described in the articles by Father MacRae and Msgr. Guarino. It is naïve to think in these cases that a bishop’s first interest is going to be the priest. It really should not surprise us, however, that we are in this state. Just as seminarians are the product of the culture whence they come, and the Church must take pains to purify them of all that is wrong with the culture, so the Church, our bishops, are products of the culture in which the Church lives. We are living in the midst of the me-too movement, of the culture of ridiculous wokeness in which some believe five- and six-year-old children need to be educated about transgender ideology and sexual identity.

This dominant culture seeks rogue justice, not repentance. It seeks conformity, not diversity. We claim rights, not just the fulfillment of duties. We live in an age of wicked hypocrisy. Priests are labelled as dirty child molesters, not men of learning on a mission. Bishops steer the difficult course of confronting all that is evil in culture while trying not to make themselves and the Church irrelevant. But at what cost? With what methods?

Pandering to the mad mob is not the answer. Rather, we need to re-claim and re-publicize that the Gospel message is one of repentance and forgiveness and a call to be perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect. We are bound to fall along the way, which is why the Second Person of the Trinity humbled Himself to be born of our human flesh. When we can regain our equilibrium after the scandals, we will be a much healthier Church, but less so if we simply discard those who have sinned but have embraced the grace of repentance. For now, as with so many other scandals and confusion in the Church, we ought as priests and laity to keep our heads down, say our prayers, and keep our Faith. This, too, shall pass. God knows when, but it will pass. How long, O Lord, how long?

+ + +

Fr. Stuart MacDonald, ordained in 1997, is a priest of the Diocese of St. Catharines, Canada. Pastor of a parish, he is currently a canon law doctoral candidate at St. Paul University in Ottawa and assists accused priests with canonical counsel. Previously, Fr. MacDonald studied canon law at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome and served as an official for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Most recently, he has been asked by Fr. MacRae to be the Canon Law Advisor for Beyond These Stone Walls.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: I thank Father Stuart for this candid and most important post on the state of priesthood in this troubled time. Both he and I want to urge readers to visit and ponder the posts cited herein by Msgr. Thomas G. Guarino in The Catholic World Report entitled, “The National Survey of Priests Suggests a Deep Crisis in Catholic Theology.”

+ + +

Father Stuart MacDonald, JCL at the Vatican

One of our Patron Saints, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, founded a religious site in his native Poland called Niepokalanow. The site has a real-time live feed of its Adoration Chapel with Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament. We invite you to spend some time before the Lord in a place that holds great spiritual meaning for us.

Click or tap the image for live access to the Adoration Chapel.

As you can see the monstrance for Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament is most unusual. It is an irony that all of you can see it but I cannot. So please remember me while you are there. For an understanding of the theology behind this particular monstrance of the Immaculata, see my post “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Forty Years of Priesthood in the Mighty Wind of Pentecost

On the Solemnity of Pentecost Father Gordon MacRae marks forty years of priesthood. Had a map of his life been before him on June 5, 1982, what would he have done?

On the Solemnity of Pentecost Father Gordon MacRae marked forty years of priesthood. Had a map of his life been before him on June 5, 1982, what would he have done?

June 1, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

+ + +

“When you were young, you fastened your belt and walked where you would; but when you are old you will stretch out your hands and someone else will fasten them and take you where you do not wish to go.”

The Resurrected Christ to Peter (John 21:18)

+ + +

The few lines just below the top image on many blog posts are sometimes called a “meta-description.” Its purpose is to provide search engines like Google a summary of a post’s content in 164 characters or less (including spaces). Our meta-descriptions are not very useful in that regard because they are written with actual readers in mind and not search engines.

Our Editor’s meta-description atop this post ends with a question: What would I have done forty years ago on June 5, 1982 if I had before me then a vision of my future life as a priest? When I was unjustly sent to prison in 1994, I was asked that question often. I never had an easy answer.

After I began writing from prison at the invitation of Cardinal Avery Dulles fourteen years later in 2008, most people had stopped asking me that question. I think most just assumed that my life as a priest was over, or that whatever was left would just collapse and vanish under the weight of prison. Some thought the Vatican would throw me overboard without evidence simply because I am in prison. After 40 years as a priest, and 28 of them as a prisoner, none of those things has happened. I am now asked a different question: What sustains an identity of priesthood in such a place?

Also atop this post is a haunting quote from the Gospel of John (21:18). It’s from an appearance of the Risen Christ to Simon Peter and the disciples at the Sea of Tiberius. Jesus sought restitution from Peter whose courage gave way to a lie days earlier at Calvary. Peter had an opportunity to live up to his own words declared on the day before the Crucifixion, “Lord, I am ready to go with you to prison and to death.” (Luke 22:23). At Calvary, as the accusing mob pressed in, Peter’s courage failed. To appease the mob, he three times denied knowing Jesus.

I wrote in a post just weeks ago, “Shaming Benedict XVI, Catholic Schism, Cardinal Zen Arrested,” that we saw faith falter when only 92 of the world’s Catholic bishops signed a letter confronting a threat of Catholic schism in Germany while most others remained silent. We saw this again as prelates in the largest Christian denomination on Earth remained strangely silent after the Chinese Communist government’s unjust arrest of Hong Kong’s 90-year-old Joseph Cardinal Zen.

And we saw it yet again when only 15 U.S. bishops spoke out in support of San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone who courageously barred U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi from Communion until she repents for decades of abject promotion of abortion. He acted as he must in pastoral care for her soul.

But I have no legitimate judgment of Peter at Calvary. It is not easy to stand up to a mob. In the verse that immediately follows the one I quote from Saint John atop this post, the Lord told Peter what would happen when he finds his faith and it informs his strength. He did find it, and Tradition tells us that he was crucified for it in A.D. 67. The flaws of bishops, which only the spiritually blind deny sharing with them in abundance, need not preclude the courage that Christ summons forth.

An Anniversary of Priesthood

A good friend, Fr. Stuart MacDonald, just celebrated his 25th anniversary of priesthood ordination. This is usually a joyful event for a priest, for his family, and for his parish. Father Stuart sent me a wonderful photograph of the Mass of Thanksgiving at his diocesan cathedral. The recently renovated church is beautiful, and the hundreds of Father Stuart’s family, friends and parishioners could not have been prouder, or happier.

Behind the main altar in the photo above is a glorious stained glass window depicting the Crucifixion of Jesus. It is difficult to look at that sanctuary and see anything else. And yet Father Stuart stands out incensing the altar for the Liturgy of the Eucharist, his appearance one of faithful witness inspired by the salvific scene of divine restitution enacted in glory just behind him.

I pondered the scene for a long time, taking in the beauty of the restored sanctuary’s art and architecture. It is all focused on that one place where priestly hands would soon raise in sacrifice the very Lamb of God Who takes away the sins of the world — even the sins of a three times denial of Him by Peter who would then become the First Bishop of Rome.

I tend not to look at such scenes and think about myself. I was so proud of Father Stuart because he, too, has endured the suffering of the Cross in his years as a priest. Like so many, he suffered bouts of depression and anxiety during the long bludgeoning of the priesthood over the last twenty-five years. It has come from all sides, even lately from some of our bishops. Father Stuart is fortunate to have one who supports him. In an age of cancelled priests, it is not always so.

It was some time before I contrasted the photograph sent by Father Stuart with the scene in my prison cell late at night on June 5, 2022, the Solemnity of Pentecost, as I offer my own Mass of Thanksgiving for 40 years of priesthood. Able to obtain elements for Mass only once per week, I join in that sacrificial offering in a 60-square-foot prison cell in the dark. The chair upon which I offer Mass is a 5-gallon plastic trash bucket emptied and turned upside down for the occasion.

There is something vaguely prophetic in that. Like the bucket, I, too, have to be emptied before Mass of all the harmful refuse of prison. At 11:00 PM, after the last prisoner count of the day, after the last of the chaos and noise that fills this place subsides, I remove my hard-earned Mass kit from a hidden shelf in a corner. The plastic storage box relinquishes a small stole, a corporal and purificator, a sturdy plastic coffee cup. It is all I have for this purpose, but never used for any other.

Lastly comes a host and a quarter-ounce vial of sacramental wine. From a shelf at the foot of my concrete bunk comes a Sacramentary and a small battery powered book light. A concrete slab protrudes from the cinder block wall at the base of the sole, heavily barred cell window. The otherwise torturous prison lights beyond provide just enough light for Mass.

The Mass is always Ad Orientam, facing East, because that is the direction toward which my window faces. I am grateful for this despite it being of no design of my own. My little booklight illuminates the Roman Canon, the Eucharistic Prayer which affords an opportunity to name the living and the dead who accompany me in this Mass. You are always remembered there.

There is no one else physically in attendance except my non-Catholic roommate who begins snoring up a storm in his upper bunk about an hour before my Mass begins. It is not exactly the hymn of a Heavenly choir, but, like most of the harsh sounds of prison, I have learned to tune it out.

So there, sitting on my bucket — ummm, I mean the big upside-down plastic one — Heaven reaches into a place where God often seems absent, but it only seems that way. When I elevate the host for the Sacrifice of the Lamb of God, it is in equal measure just as glorious as the Cathedral altar scene where Father Stuart made that same offering. After 40 years, this may seem to some to be all that remains of the visible manifestation of my priesthood. It is a miracle in its own right, one that I described on an earlier anniversary of ordination in “Priesthood in the Real Presence, and the Present Absence.”

In the Mighty Wind of Pentecost

But there is another manifestation of priesthood less visible than my weekly offer of Mass, but just as mysterious and powerful. It has to do with the day on which my 40th anniversary of priesthood falls. It has to do with Pentecost, a Greek term meaning “fiftieth.” In Jewish tradition, it is called “Shavuot,” the Feast of Weeks. It falls on the sixth day of the Hebrew month, Savon, the concluding day of the Omer, the 49 days (seven weeks) from the Passover commanded in Leviticus (23:15-16).

In the Book of Exodus (23:16), it became the Harvest Feast. In Rabbinic legend, it was also the day Yahweh gave the Law — the Torah — to Moses on Mount Sinai in Exodus 19. It is the second of three annual feasts requiring a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. It was the reason that Mary, the Mother of Jesus, Peter, and the disciples were in Jerusalem with so many others. A seminary professor once told me that “salvation comes from the Jews. They are our spiritual ancestors, and we must honor them.” I do.

It is because they were Jews that they were in Jerusalem on the Day of Pentecost. In the Christian tradition, it is celebrated on the Seventh Sunday of Easter and closes the Easter season. Technically, it is the day after 49 days (or seven weeks) following the final Passover meal of Jesus and the Apostles, the point through which the Jewish and Christian traditions are intimately connected. It was also the day that Jesus was betrayed, the point at which Salvation History begins its fulfillment. For a deeper understanding of this, see my post, “Satan at the Last Supper, Hours of Darkness and Light.”

In the Book of Acts of the Apostles (Ch. 2), the disciples of Jesus are gathered in Jerusalem in one house: then suddenly ...

“A sound came from heaven like the rush of a mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared to them tongues as of fire, coming to rest upon each one of them. And they were filled with the Holy Spirit.”

— Acts 2: 1-4”

The scene recalls the fiery descent of the Spirit of God at Mount Sinai during the Exodus from Egypt (Exodus 19:16-19).

As that driving wind filled the room where the Apostles were gathered, “men of every race and tongue, of every people and nation” emptied into the street at the strange and powerful sound. Filled with the Holy Spirit, the Apostles began to address the bewildered crowd, each person hearing them speak in his own native tongue. In the Book of Acts, the Holy Spirit filled not only the Apostles, but some of the crowd as well, “and there were added that day about three thousand souls” (Acts 2:41).

That day in Catholic understanding is the birth of the Church, and by the time it was only an hour old, its first scandal broke out. Those in the crowd who did not inherit the wind immediately accused the Apostles of being drunk at 9:00 AM on a major holy day that required a fast. Their pharisaical claim caused Peter, now the leader of the Twelve, into the first papal defense of the Church:

“Men of Judea and all who dwell in Jerusalem, let this be known to you and give ear to my words. These men are not drunk as you suppose. It is only the third hour of the day.”

Acts 2:14-15

Inspired by the Spirit, Peter went on to preach the Church’s first homily, relying on the Prophet Joel (2:28-32) to explain that God has poured out His Spirit because the Messianic Age had begun. The meaning of the Passion of the Christ was unveiled.

It is interesting that the word for both wind and breath in Hebrew is “ruah,” and the term in Hebrew for the Holy Spirit is “ruah ha-Qodesh.” It simultaneously means the Spirit of God, the Wind of God, and the Breath of God. The same term is used in the story of Creation (Genesis 1:1-2):

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God, ‘ruah ha-Qodesh,’ was moving over the waters.”

— Genesis 1:1-2

And the term was used again in Genesis 2:7 as God breathed the Spirit into the nostrils of Adam, and yet again in a Resurrection appearance of Jesus to the Apostles, “He breathed on them and said, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit.’” (John 20:22)

The Wind of God did just as Jesus predicted it would do to Peter in the Gospel quote that began this post. It bound my hands and took me to a place where I did not wish to go. What am I to make of this? What should I have done while laying face down on the floor before an altar as the Litany of Saints offered me up in priestly sacrifice forty years ago? What would I have done then had a vision of my future life as a priest been before me?

When I look back on forty years of priesthood, most of them in exile, imprisoned souls were reached through no merit of my own. In spite of myself, the Wind of God took me up in its vortex, and I am simply blown away by it.

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Please share this post and please also visit our updated Special Events page. You may also like these related posts.

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

Priesthood in the Real Presence, and the Present Absence

Priesthood, the Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times

Bishops, Priests and Weapons of Mass Destruction

Pope Francis promulgated Vos estis, a law applicable to bishops. Previously, if a bishop was accused of a canonical offense, only the Pope could bring him to task.

Pope Francis promulgated Vos estis, a law applicable to bishops. Previously, if a bishop was accused of a canonical offense, only the Pope could bring him to task.

Recently, behind the scenes at Beyond These Stone Walls, people have been working to restore and update Father Gordon MacRae’s older posts and save them in multiple categories in the Library at BTSW. One of the categories is Catholic Priesthood where this post, I expect, will find its permanent home. One such article was “Goodbye, Good Priest!” It was an updated reflection on the story of Father John Corapi, posted anew without any notice or fanfare. Nonetheless, it received more than 6,000 visits and 3,700 shares on social media in the first 24 hours after it was posted. This happened even before Fr John Zuhlsdorf — the famous Fr Z — posted a link to another blog informing readers that Fr Corapi, thanks be to God, had reconciled with his religious order several years ago and has been living a quiet life of prayer in one of its community houses. Fr Z’s post was “If you do not forgive men their trespasses neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.”

We had not heard about Fr Corapi for many years. His, we thought, was one of the many forgotten tales about priests, guilty, or even merely accused, of horrendous sins, whose cases often were treated with little regard for human, civil or canonical rights or due process. Fr Gordon and I were commenting that, being reminded of Fr Corapi, we realize that we have not progressed very far in the last twenty years. What Fr Gordon and I see now is that Father Corapi’s case was a small seed planted in our collective psyche that has germinated, now affecting all priests.

When the sexual abuse scandal exploded in the American press in 2002, many bishops were faced with the reality that their predecessors had known about sexual abuse of minors by priests and handled it in a way that was seen as pastoral at the time but which failed to meet today’s expectations. Back then, accused priests were shuffled off for psychological treatment, reassigned on the advice of the medical professionals to new parishes for a fresh start; sometimes they reoffended, or quietly retired to live in peace with their consciences. Even though the Vatican quietly had promulgated new laws in 2001 to deal with the crime of sexual abuse of a minor among some other of the more serious offenses in the Church, in the wake of the Boston Globe’s 2002 exposé, bishops threw up their hands and said to the Vatican, “My predecessor did this; you have to help me get out of this mess!”

And so dawned the era of the Dallas Charter. In the face of unrelenting public pressure and criticism, the Church, beginning in the United States but soon almost everywhere, began to treat allegations as proven crimes, to treat priests like chattel, to put money over preaching the Gospel. The Dallas Charter ushered in an era that means one strike and you’re out, and, in fact you don’t even have to prove that it was a strike: credibly accused quickly became the operative expression. In effect, the first decade of the 21st century witnessed the Church take on the notion that the priesthood was more disposable than it ever had been before. It was a reaction of fear.

Soon after, file upon file was sent to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) as bishops scoured their personnel files for any priest previously accused of sexual abuse. Even though the case had been dealt with already, according to the pastoral plan mentioned above, current bishops were looking for Rome to revisit the case and, it was expected, remove the priest permanently from ministry if not the clerical state itself. The caseload became so heavy that the CDF had to notify bishops that a deadline was being set after which no historical cases could be submitted. Apparently, someone had forgotten to inform everyone involved that law, especially penal law, cannot, in justice, be applied retroactively.

So far, we have only been talking about accusation of sexual abuse of minors. Fr John Corapi was never accused of that. He was accused of sexual misconduct, perhaps even concubinage, with an adult woman among supected financial misdeeds. In the heat of the abuse scandal, his case was being treated as if the Dallas Charter applied, which it did not. Father Corapi realized that he would never be treated according to the canon law of the Church. He knew he was considered guilty; nothing was going to change that, so he walked away. It is a sad commentary on the Church that such a gifted man was driven to near despair, that Church officials could be so indifferent to basic tenets of justice and due process. But that’s where we were.

Jump forward several years. In 2019, Pope Francis promulgated Vos estis, a set of laws applicable to bishops. Prior to those laws, bishops were directly responsible to the Pope alone. If a bishop was accused of a crime, like sexual abuse of a minor, only the Pope could bring him to task. Canon law assumes that people with authority in the Church, like bishops, are not saints, but at least God-fearing men seeking virtue. In fact, canon law only really works when that’s the case. People like Theodore McCarrick, the former Cardinal and Archbishop, got away with his misconduct for so long because a lot of bishops are not God-fearing men. McCarrick was relieved of his clerical obligations in 2019 and is now a layman.

With everything the Pope has to do, he certainly does not have time to micro-manage the lives of 5,000 bishops. The problem, becoming apparent, was that not only priests were being accused. The ravenous press and hysterical crowd were not satisfied. Bishops were next on the hit list. Hence, Pope Francis set up a system whereby bishops are now accountable for their own misconduct, even historical accusations from when they were yet priests. They are accountable, as well, for how they handle, as bishops, accusations of sexual abuse of minors by priests subject to them. With Pope Francis’ new legislation, the Congregation for Bishops is authorized to investigate accusations made about bishops in much the same way that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was authorized in 2001 to do the same regarding priests. This is new territory and bishops are clearly anxious.

Guilty Merely for Being Accused?

Since the promulgation of Vos estis, several bishops have been removed from office or disciplined in some way: Bishop Richard Malone, emeritus of Buffalo; Bishop Michael Bransfield, emeritus of Wheeling-Charleston; Archbishop Henryk Gulbinowicz, emeritus of Wroclaw, Poland; Bishop Michael Hoeppner, emeritus of Crookston to name just a few. It’s a new world out there since 2019. What bishops have done to priests since 2002 is now being done to them.

“ The measure with which you measure will be measured out to you.”

Pope Francis, in Vos estis, expressed his wish that bishops conferences set up confidential reporting mechanisms such that people who know of misconduct committed by a bishop could safely report it knowing that action would be taken to investigate. The Canadian bishops conference announced a few weeks ago just such a mechanism. Anyone can now call a confidential line, or submit an online report, to a third-party agency which will receive the information and, in turn, pass on a report to the appropriate bishop. That bishop, in receipt of the report, will consult the Congregation for Bishops on how to proceed. Whatever else it is, and it is many things, this move is a lot of virtue signaling. Nothing guarantees that the report will be taken seriously. The only certainty is that a secular third party is being paid to receive and pass on information.

There is no real transparency to the procedures that are used to investigate a bishop — and I’m not arguing there should be, in this or any investigation of a priest — it is not evident that such things belong to the realm of public knowledge. Instead, we must trust that what is being done is just and legal — there’s no sense having a code of law in the Church if it means nothing or is not going to be used. Unfortunately, the Church’s track record in this regard leaves us with very little trust. With these new initiatives, nothing says that the bishop reporting to Rome about his brother bishop will not convince the Vatican that the allegation is unfounded or exaggerated. And, to be fair, understand that the Vatican has to trust the bishop consulting them. If they can’t, how is the Vatican to know and what is it supposed to do? We’re back to the headline: “Needed: God-fearing men trying to live lives of virtue.”

Now that bishops are being held to the same standards, or lack thereof, they have become hypervigilant of their priests, or, rather, of their own reputations. Virtue signaling abounds: bishops are tough on clerical misconduct. Now, not only accusation of sexual abuse of a minor leads a bishop to remove a priest from ministry, but, indeed, any misconduct whatsoever. That was the seed planted by Father Corapi’s case. Anything done by a priest that is going to cause publicity, or a lawsuit, is now treated in the same way as an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor. A priest is put on so-called administrative leave, his faculties are removed, he is not allowed to perform any priestly ministry except the celebration of Mass in private, which means alone.

This is all done, they say, just like they did in the early 2000’s, pro bono ecclesiae — for the good of the Church. This is being done by bending the law to the point of breaking. What priest, especially if he is guilty of something, is going to challenge his bishop’s abuse of the law. Priests who have been accused of misconduct, not involving minors, are now being removed from ministry under the guise that they are not suitable for assignment because of their misconduct, even though that misconduct may have been adjudicated and punished already — justly or not is another question. Bishops go so far as to encourage the priest to petition for laicization. The bishop can’t force a priest out of the priesthood because whatever he is alleged to have done doesn’t warrant such a punishment. But the bishop doesn’t want to be responsible for the ‘unassignable’ priest for the rest of his life, nor does he want to continue paying the priest.

Check any “Policy for Cases of Misconduct” published by a diocese. Many of them have clauses that say a priest found guilty of misconduct will never minister in the diocese again. Of course, such clauses are not allowed by canon law. No one questions what procedures will be used to determine the guilt or innocence of the accused priest. But what looks good is the policy itself. The Church has gone tough, not just on abusing minors, but on any misdeed. Try to find a definition of misconduct, or a list of behaviors that is classified as misconduct — you won’t. Vague is good: it allows those in authority to cite the law while interpreting it as they wish. Those are the parameters we are operating within today.

Fear and panic, there’s the problem. Instead of turning to Christ, we look to the world for our sense of self-worth as a Church. Are we held to impossible standards by the world? Yes. Does the world despise us because the Gospel preaches something counter-cultural? Yes. Are they going to sue us for every penny we own? Probably. Jesus told us, “If the world hates you, be aware that it hated me before it hated you” (John 15:18). The Church certainly has made mistakes in the last half-century or more. One of the biggest ones was turning a blind eye to immorality, especially sexual immorality among clergy and the faithful. In its zeal to be pastoral as a way of opening up to the world — a mantra of Vatican II — she failed to enforce her laws, or use her laws to bring justice and transparency to cases of crime and misconduct. The way out of this mess is not more laws, not more father turning on son and brother on brother tactics reminiscent of Nazi Germany. The answer is to read and heed the Gospel.

“For They Do Not Practice What They Preach” (Matthew 23:3)

In July 2013, Pope Francis was questioned about a Monsignor whom the Holy Father had appointed to a Vatican office. The Monsignor, according to reports, engaged in homosexual activity several times. The press wanted to know from the Pope how this person could be assigned given his past. Pope Francis came out with his now infamous line, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” The press, to this day, wildly misinterprets what the Holy Father said, namely, that someone who was seeking the Lord with good will, i.e., repenting of past sin and seeking the right path, ought not to be judged by us. The rationale behind that is nothing other than the whole Christian message: Christ died so that all of us sinners could be redeemed. The Pope was saying, in essence, that someone could be a very sinful person, but repentance is always possible. Furthermore, he was pointing out that someone’s sinful past does not necessarily disqualify one from working in the Church — to be sure, sometimes it does, but not always. How would any of the apostles survive as priests or bishops in today’s climate?

In our Lord’s day, the religious leaders were worried about the popularity of Jesus. They didn’t want the people, the mob, to turn against them. In the end, it was they who, in the midst of the mob, told Pilate that they had no King but Caesar. It was they who instigated the mob’s choice of Barabbas over Jesus. The mob can be a frightening place when we have lost sight of Heaven. Jesus Himself was confronted with a mob. When they brought to Him the woman caught in adultery, the mob was after Him, not so much the woman who had been caught flagrantly in sin. They wanted to trip Him up about the law. Jesus was uncowed by their bullying. He didn’t lash out at the mob; rather, he showed them mercy by His retort, “Let anyone who is without sin, cast the first stone.” He gave the mob room to see its error. The Gospel of John (8:3-11) points out the seemingly insignificant detail that Jesus looked down so that they could walk away while saving face.

At the same time, Jesus healed the woman, wounded by her own sinfulness and maltreated as a pawn by the mob. He sends her off, with the consolation of “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again” (John 8:11). Our Lord showed that the mob, the world, CAN learn the truth about sin and redemption. He showed her that compunction was enough to receive mercy and the need to learn from one’s sins. He did not tell her not to pay attention to the Pharisees — in fact, in another place Jesus warned the people, “Obey them and do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach” (Matthew 23:3). He didn’t say they were not qualified for the job as Pharisees because they were sinful. He also told her to learn from the mercy she received and to put aside her sinfulness. All of that is an important meditation for us because little mercy is being shown priests.

When I think of Father Gordon MacRae and the injustice he is enduring with such equanimity and grace, I am reminded that God’s grace is still active in this messy world. Beyond These Stone Walls is a visible sign of grace, allowing Father Gordon to preach from his pulpit, his unjust imprisonment, to make so many aware of the reality of injustice even in the Church. He and this blog are a sign of grace, a sign that such corruption is not a reason to turn against God or His Church but to work even harder to bring about a community of God-fearing men trying to live lives of virtue.

+ + +

Fr. Stuart MacDonald is a priest of the Diocese of St Catharines, Canada. Ordained in 1997, he is a graduate of McGill University, St. Augustine’s Seminary and the Pontifical Gregorian University where he earned a licentiate in Canon Law. In addition to being pastor of various parishes, he has worked as a judge and defender of the bond for the Toronto Regional Marriage Tribunal and as an official for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith at the Holy See. He is the author of several published articles on Canon Law and the priesthood. His most recent post for BTSW was “On Our Battle-Weary Priesthood.”

You may also want to read and share these related posts: