“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Canon Law Conundrum: When Moral Certainty Is Neither Moral Nor Certain

Convoluted moral justification is employed by Jesuits of the USA Central and Southern Province to publish a list of priests with ‘credible’ allegations of abuse.

The Stoning of Saint Stephen by Rembrandt

Convoluted moral justification is employed by Jesuits of the USA Central and Southern Province to publish a list of priests with ‘credible’ allegations of abuse.

May 3, 2023 by Michael J. Mazza, JD, JCD

Introduction by Fr. Gordon MacRae: It is an honor and a privilege to publish this important guest post by Michael J. Mazza, JD, JCD, (pictured below at the Vatican) a highly regarded canon lawyer, civil attorney, and law professor with broad experience in the canonical defense of Catholic priests. His post is a sequel of sorts to my post in these pages last week, “Follow the Money: Another Sinister Grand Jury Report.” His post introduces us to a newly articulated standard for removing priests from ministry adopted by a Jesuit Province in the United States. It is a standard that left me shuddering over the rapid decline of due process rights for priests. Like other such draconian standards, I fear its use will spread like a virus.

Back in August, 2019, Ryan A. MacDonald wrote a featured post for Beyond These Stone Walls entitled “In the Diocese of Manchester, Transparency and a Hit List.” It has been one of our most widely read posts of recent years and continues to be so. Ryan wrote about the injustice of publishing names of accused priests when the basis for deeming a claim to be ‘credible’ is a standard of justice not employed or even recognized in any other legal forum. It essentially means that an allegation of abuse is only “possible,” but not necessarily “probable.” It should be the beginning of a Church investigation, but it has widely become the end.

This is a standard that is now employed by nearly every bishop in every diocese, and it is rapidly spreading throughout the Church. Michael Mazza’s post to follow understandably has a bit more ‘legalese’ than usually comes from my typewriter, but it is a brilliant eye-opener.

There was a smoldering cloud just above my head as I three times read the Jesuits’ confounding justification for censuring and removing priests. In a word, it is mind-boggling.

This post shines a much needed light on the need for canonical justice and advocacy for accused priests. It is highly recommended to us by Fr. Stuart MacDonald, a frequent Beyond These Stone Walls contributor and a candidate for the Doctorate in Canon Law. Please share this post widely, especially among the priests you know.

When Moral Certainty Is Neither Moral Nor Certain

Two months ago the Jesuits USA Central and Southern Province released an updated registry of Jesuits with “credible allegations of sexual abuse of a minor.” As a canonical advocate representing priests accused of misconduct, I was involved in one of the cases referenced. Given the requirements of canon law and my professional duties, I am limited in what I can say about the case. What I can discuss — in fact, what I feel I must rectify — is the grievous error of law contained in the Jesuit Province’s published statement, a mistake that despite my best efforts has gravely damaged the reputation of a good priest and respect for the rule of law in the Church.

The most problematic part of the statement appears in its first paragraph:

“For the purposes of this list, a finding of credibility of an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor is based on a belief, with moral certitude, after careful investigation and review by professionals, that an incident of sexual abuse of a minor or vulnerable adult occurred, or probably occurred, with the possibility that it did not occur being highly unlikely. ‘Moral certitude’ in this context means a high degree of probability, but short of absolute certainty. As such, inclusion on this list does not imply the allegations are true and correct or that the accused individual has been found guilty of a crime or liable for civil claims.”

It is difficult to know where to begin with an analysis of this confounding passage. Did the event happen or not? We are told on the one hand that being included on the list “does not imply the allegations are true and correct.” At the same time, however, we are told that “after careful investigation” and “review by professionals,” the allegation has been determined “with moral certitude” to have “occurred or probably occurred.” In fact, the statement says the possibility that the events did not occur “is highly unlikely.”

While such a confusing statement may appear to have been crafted by two opposing camps of a drafting committee, the real world consequences of it were clear, especially because it was accompanied by the usual invitation for victims of abuse to come forward. The news was reported as a “shock” to the students at the university where the priest had been a popular professor, leaving some brokenhearted and in tears. A theology professor said the news had “shaken” him and his colleagues, with one priest colleague concluding thus: “It’s mind-boggling that anyone would do such a thing, period end of story.”

Conclusions like these are not surprising. What is surprising — and what ought to be profoundly disturbing to those who value the rule of law — is that they have no legal basis whatsoever. Like so many of his priestly brethren in the USA accused of canonical crimes these days, the priest at issue was never given the benefit of a trial during which he could have defended his innocence. Instead, the priest was on the receiving end of what is known in canon law as a “preliminary investigation,” a technique under canon 1718 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law that is designed solely to determine whether there is sufficient indicia to warrant the launching of a full-blown canonical process. Only after this formal process, whether judicial or administrative, may a penalty be inflicted or declared. And it is only through this formal process that “moral certainty” — the canonical equivalent of “beyond a reasonable doubt” — may be achieved under the law.

An analogy may prove helpful here. Suppose that Mary, a juror in a domestic abuse trial, learns of allegations that John abused Jane. Mary hears from Jane, the only witness at the trial, about the details of her charge. Mary knows only that John denies the accusation, but does not hear from him because John is not present at the trial. In fact, neither John nor his defense counsel is even invited to the trial. If Mary nevertheless arrives at John’s guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt,” in spite of the fact that John was not allowed to exercise his natural human right to self-defense, what would we say about Mary’s judgment?

All analogies limp, and several objections could immediately be raised with respect to this one. Just because there were no other witnesses does not mean that there was no abuse, a sin and a crime that is horrible and was often covered up in the past, especially in ecclesial circles. While these statements are certainly true, summarily dismissing valid concerns about violations of the due process rights of accused clerics is not a solution to the sex abuse crisis. On the contrary, it only perpetuates a continuing injustice and creates an atmosphere of fear, mistrust, and division within the ecclesial community. That is not a sustainable path forward.

It needs to be emphasized that a canonical preliminary investigation is typically performed by an individual (most often but not always a former law enforcement official) whose only job is to assemble indicia substantiating an allegation. The investigator then presents these indicia to a review board, generally constituted by lay people (at least some of whom are to have experience in law or psychology), who make a recommendation to the religious superior or bishop about whether a full-blown canonical investigation should be initiated.

In some ways, the work of a review board is similar to that of a grand jury. Grand juries, like review boards, are supposed to act as shields against arbitrary, unfounded, and malicious accusations of wrongdoing by ensuring that serious accusations are brought only upon the considered judgment of a representative body acting according to the rule of law. Grand juries, like review boards, do not decide whether the accused is guilty; they merely decide whether there is probable cause to believe that a crime occurred and probable cause to believe that the person accused committed that crime. In short, grand juries, like review boards, decide only whether there is enough evidence to proceed to the next stage in the judicial process.

This is because of the deliberately one-sided nature of grand jury proceedings. Only the prosecutor — not the defense — gets to address the grand jury. All of the important safeguards of justice are saved for the real trial that comes only after the grand jury has performed its important task. Nevertheless, all this means that in a very real way the life and reputation of a fellow citizen are in the hands of the grand jurors. Indictments, like recommendations from review boards, often receive press coverage in which these legal niceties are overlooked, meaning that the reputation of the person accused is harmed and his life thrown into turmoil.

Many accused priests never get a trial, “period end of story.” Nevertheless, their lives are thrown into turmoil, beyond any doubt. What do we make of subsequent decisions by accused clerics to abandon the fight, or to leave religious life and/or the active priesthood? One could certainly infer guilt from it, and many people do just that. But isn’t it also possible that there are other reasons for such momentous decisions? With no forum to clear their names, and in spite of repeated and consistent denials of the charge — and the lack of any criminal proceedings or any record from a related civil trial — isn’t it at least possible that some clerics simply despair of ever clearing their names and just decide to move on with their lives as best they can?

Catholics should be very wary of making judgments about their fellow human beings. We have been cautioned against it by Our Lord himself (see, e.g., Mt. 7:1-3). In fact, as legal scholar James Q. Whitman has shown in his 2016 book The Origins of Reasonable Doubt, the original basis for the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard was to encourage reluctant jurors to reach guilty verdicts when the evidence pointed strongly in that direction. Why were they reluctant? Because they feared judging their neighbors, both because of the possible vengeance of the guilty person’s relatives in this world and because of their belief in being judged in the next world.

None of what has been stated in this article is unknown to the American bishops — or, even more importantly, to their lawyers. In fact, in November 2000 the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops issued an insightful commentary on the American criminal justice system entitled “Responsibility, Rehabilitation, and Restoration: A Catholic Perspective on Crime and Criminal Justice.” That statement, as of this writing, is still available on the USCCB website. Issued less than two years before the Dallas Charter, the document criticizes notions such as “zero tolerance” and “simplistic solutions such as ‘three strikes and you’re out,’” with the latter being labelled specifically as a “slogan of the moment.” The paper goes on to quite rightly assert that “crime, corrections, and the search for real community require far more than the policy clichés of conservatives and liberals.”

Notwithstanding such statements, real harm is happening to real men on a daily basis in this country in the name of “transparency.” Perhaps few priests in America know the pain that such sloganeering can inflict as Father Gordon MacRae. Incarcerated for almost three decades after a trial described as “Kafkaesque” by Fr. Richard John Neuhaus. Fr. MacRae not only steadfastly maintains his innocence, but from his prison cell faithfully maintains his website “BeyondTheseStoneWalls.com,” dedicated to drawing attention to the plight of his brother priests and the dangers wrought by violations of the right to due process. MacRae’s case stands as an especially stark example of how pre-trial public statements from his diocese prejudiced his cause, defamed him, and likely helped lead to his wrongful conviction.

In summary, it is essential to note that judging cases involving allegations of child sexual abuse is an enormously painful and difficult process for all involved: the accuser, the accused, and all those involved in the case. Decisions one way or the other can be life-altering. They are not made any easier by those who comment upon them without a firm understanding of both the facts and the applicable law. While legal processes do not come with a guarantee of infallibility, they are a time-tested tool used throughout the centuries for the determination of facts. Legal principles such as moral certainty, the presumption of innocence, and the duty to refrain from unfairly violating someone’s right to a good name are, likewise, bedrock principles of any society. We neglect these valuable tools at our peril.

+ + +

About the Author: Michael J. Mazza, JD, JCD graduated summa cum laude in 1999 from Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee where he was Editor in Chief of the Law Review. He subsequently clerked for the Hon. John L. Coffey on the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago. After 20 years in civil law practice, Michael began studies in canon law at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome from where he graduated magna cum laude in 2021 with a license in canon law (JCL)

In 2022, Michael successfully defended his thesis for the Doctorate in Canon Law (JCD). His topic was also the topic of an excellent article published in the Tulsa Law Review: “Defending a Cleric’s Right to Reputation and the Sexual Abuse Scandal in the Catholic Church.”

Michael is today an adjunct professor of canon law at Marquette University and at Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology outside of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He also represents clients in need of canonical counsel, especially accused priests. If any priest needs canonical assistance Michael can be reached through his website at www.CanonicalAdvocacy.com or by email at mjmazzajdjcd@pm.me.

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: I am most grateful to Professor Mazza for this alarming but important chapter in the cause of justice and due process for priests. You may also like to read and share these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls :

Follow the Money: Another Sinister Sex Abuse Grand Jury Report by Fr. Gordon J. MacRae

Bishops, Priests and Weapons of Mass Destruction by Fr. Stuart MacDonald, JCL

In the Diocese of Manchester, Transparency and a Hit List by Ryan A. MacDonald

Priests in Crisis: The Catholic University of America Study by Fr. Gordon J. MacRae

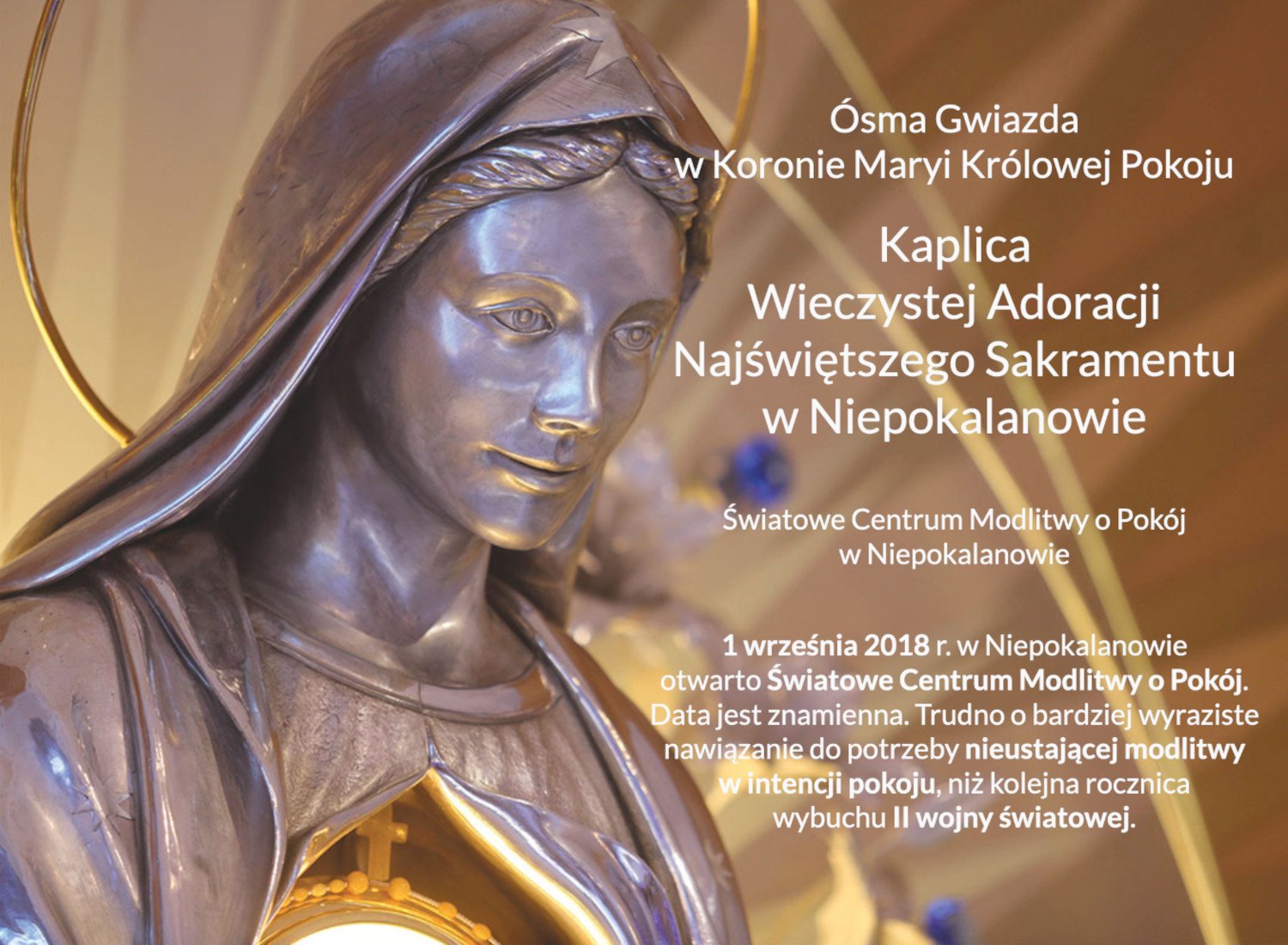

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

In the Diocese of Manchester, Transparency and a Hit List

Citing “transparency” the Catholic Diocese of Manchester posted the names of 73 accused priests. Most are dead. The only one in prison is innocent, and they know it.

Citing “transparency” the Catholic Diocese of Manchester posted the names of 73 accused priests. Most are dead. The only one in prison is innocent, and they know it.

August 21, 2019 by Ryan A. MacDonald (last updated April 8, 2024)

Note: The following is a guest post by Ryan A. MacDonald whose previous articles include “#MeToo & #HimToo” and “Justice and a Priest’s Right of Defense in the Diocese of Manchester.”

Michael Voris, former moderator and podcast host of Church Militant, had been posting some eye-opening commentary about a story from the Archdiocese of Detroit. Church officials there, in apparent disregard for canon law, published the name of a priest who has been accused of sexual misconduct. The priest is Father Eduard Perrone.

Reportedly, the Archdiocese published his name and a statement that the claims against him are “credible” while steadfastly refusing to publicly acknowledge the fact that Father Perrone maintains his innocence and has a right of defense. Church Militant reported that the original claim is forty years old and came from “a repressed memory,” a highly dubious and dangerous source according to experts in the field of psychology.

Weeks later, attorneys for Father Perrone issued a statement that he has conclusively passed a series of expert polygraph examinations that support his innocence. To date, the Archdiocese has been unresponsive to that fact as well, and so has the Catholic news media commenting on the story while acting as little more than a public relations outlet for the Archdiocese. This all has a chilling ring of the familiar.

On Wednesday, July 31, 2019, for no apparent reason other than the fact that everyone else is doing it, Bishop Peter A. Libasci of the Diocese of Manchester, New Hampshire published a list of 73 Catholic priests accused of sexual abuse of minors. Fully two-thirds of the priests named on the list are dead and thus in no position to defend themselves. The only one currently in prison is innocent. Officials of the diocese publicly suppress that fact after privately admitting it. So much for transparency.

The treatment of Father Eduard Perrone in the Archdiocese of Detroit pales next to the sabotage of justice and basic civil rights that took place in New Hampshire in the case of Father Gordon MacRae. Refusing multiple plea deals offering him a mere one year in prison in 1994, MacRae was asked by his lawyer to consider taking a series of polygraph tests with an expert.

Like Father Perrone in Detroit, MacRae agreed without hesitation.

He was scheduled for three polygraph exams with questions based on police reports itemizing the specific claims of each alleged victim. The third one was cancelled because MacRae passed the first two so conclusively. When that fact was made known to the Diocese of Manchester before jury selection in MacRae’s 1994 trial, the Diocese published a press release with this statement:

“The Diocese mourns with those who were victimized prior to the discovery of his problems… The Church has been a victim of the actions of Gordon MacRae as well as these individuals.”

There was little left for a jury to do. Armed with that statement, Prosecutor Bruce Elliott Reynolds compared MacRae to Hitler in his closing arguments before a heavily manipulated jury. A decade after the trial, a second prosecutor took his own life.

In a case brought twelve years after the alleged crimes, with no evidence of guilt at all to review and weigh, the jury reached a verdict of “guilty” on all charges in only 90 minutes. This account has been vividly exposed by Dorothy Rabinowitz in a series in The Wall Street Journal concluding with “The Trials of Father MacRae.”

The Predecessor: Bishop John McCormack

After his 1994 trial, MacRae had languished in prison with little contact with or from the outside world for the next seven years. Five years after the trial, Bishop John McCormack arrived in Manchester after a stint as Auxiliary Bishop of Boston promoted by Cardinal Bernard Law.

In 2000, rumblings began to occur pointing to some troubling media interest in the case of Father Gordon MacRae — troubling, at least, to those who put him in prison and kept him there. The initial hints of inquiry came from The Wall Street Journal and PBS Frontline. The media interest ultimately resulted in the creation of two sworn affidavits by persons entirely unrelated and unaware of each other. The following is an excerpt from the affidavit of a New Hampshire attorney:

“Upon acting in a clerk capacity for [the 1994 trial] I became firmly convinced that the charges against Father MacRae were false and brought for financial gain… In June of 2000, I met with New Hampshire Bishop John McCormack at the Diocesan office in Manchester, New Hampshire. During this meeting with Bishop McCormack and [Auxiliary] Bishop Francis Christian, they both expressed to me their belief that Father MacRae was not guilty of the crimes for which he was incarcerated.”

Four months later in 2000, an official of WGBH-TV, the flagship PBS station and production house in Boston, arranged a meeting with Bishop John McCormack. In that four-month period, something happened that drove off auxiliary Bishop Christian who was — by the way — the author of the press release declaring MacRae guilty before jury selection in his trial. What follows are excerpts of a sworn affidavit from the WGBH official:

“The WGBH Educational Foundation wanted to produce a segment of Frontline. This production would have resulted in a national story about Father MacRae. I had contacted assistant Bishop Francis Christian from my office at WGBH to inquire about the story because he was the only person remaining in the Manchester Chancery Office who was present during the time of the accusations against Father MacRae. Bishop Christian wanted nothing to do with my inquiry regarding Father MacRae but did offer to arrange a meeting for me with Bishop McCormack.

“The [October 2000] meeting with Bishop McCormack began with him saying, ‘Understand, none of this is to leave this office. I believe Father MacRae is not guilty and his accusers likely lied. There is nothing I can do to change the verdict.’”

Far more telling, however, is a transcript of notes documented by the PBS official Leo Demers after his meeting with Bishop McCormack. The notes reveal a diocese compromised by the demands of lawyers and insurance companies and a Bishop struggling to retain his moral center in a time of moral panic. The transcript was compiled in 2000, but MacRae was unaware of it until 2009 when a former FBI agent began to investigate. Here are excerpts:

[Auxiliary] Bishop Christian: “This is not my responsibility. I have nothing to do with that. You’ll have to speak with Bishop McCormack.”

Leo Demers: “But you were part of what happened at that time and would have firsthand knowledge of all that occurred. Bishop McCormack was in Boston when all this happened… I would rather meet with you.”

[A few days later I received a phone call from a Chancery Office secretary regarding a meeting schedule. I explained that I would be in the Middle East and Rome for the next two weeks. The meeting was scheduled for Friday, October 13, 2000. I arrived at the Chancery Office and was escorted to the Bishop’s office… The first words out of his mouth were…]

Bishop McCormack: “I do not want this to leave this office because I have struggles with some people within the Chancery office that are not consistent with my thoughts, but I firmly believe that Father MacRae is innocent and should not be in prison… I do not believe the Grovers [accusers at trial] were truthful.”

Leo Demers: The Grover brothers viewed this Chancery Office as an ATM machine, and why shouldn’t they? They’ll likely be back to make another withdrawal.”

Bishop McCormack: “You know that I cannot discuss any settlement agreements.”

Leo Demers: “The specifics of settlements are of no concern to me. What concerns me is the ease with which such settlements are reached.”

Bishop McCormack: “I mentioned to you that I believe he is innocent.”

Leo Demers: “You said that your hands were tied because of your belief in his innocence. How can you help him?”

Bishop McCormack: “I want to do what I can to make his life more bearable under the circumstances of prison life. I cannot reverse the decision of the court system. What can I do?”

Monsignor Edward J. Arsenault

It is striking who is not on the newly released list of accused Manchester priests. Former Monsignor Edward J. Arsenault is not found there. At the time he was elevated to “Monsignor” in 2009, Arsenault landed a $170,000 per year position as Executive Director of St. Luke Institute in Maryland. Simultaneously, Arsenault billed for over $100,000.00 in “consultation” services for Catholic Medical Center in New Hampshire. Bishop John McCormack was the sole U.S. bishop serving on the St. Luke Institute Board of Directors at that time.

Most of those who are today involved in an investigation of the case against Father MacRae believe that Arsenault was the person referred to in Bishop McCormack’s statement to the PBS Executive above:

“I do not want this to leave this office because I have struggles with some people within the Chancery office that are not consistent with my thoughts, but I firmly believe that Father MacRae is innocent and should not be in prison.”

Over the previous two years, Arsenault had risen to become McCormack’s right-hand man and the hub of all diocesan administration and finances. By 2001, Father Arsenault had effectively become the power behind the diocesan throne. In that capacity, according to his resume published online (but since removed), Arsenault personally negotiated mediated settlements in over 250 claims of sexual abuse alleged against priests of the Diocese of Manchester.

The newly published list of these accused priests is deceiving. Most claims were never brought before any court of law, but were simply demands made by letters from lawyers representing the claimants whose claims were often thirty or forty years old. In 2002, Plaintiffs’ attorney Peter Hutchins, who later claimed to have received 250 such settlements — a curious coincidence — revealed the climate in which these settlements were made. The following newspaper excerpts are from “NH Diocese Will Pay $5 Million to 62 Victims,” (Mark Hayward, NH Union Leader, Nov. 27, 2002):

“The Catholic Diocese of Manchester will pay more than $5 million to 62 people who claim they were abused by priests… The incidents took place as long ago as the 1950s and as recently as the 1980s and involved 28 priests… The Diocese disclosed the names of the priests.

“None of these men will exercise any pastoral ministry in the Church ever again,” said the Rev. Edward J. Arsenault, delegate of the Bishop for Sexual Misconduct.

“‘It shows good faith on the part of the diocese that victims of abuse will be treated and that their needs will be met,’ said Donna Sytek, Chairman of the Diocesan Task Force on Sexual Abuse Policy [and now Chairperson of the New Hampshire Parole Board].

“‘During settlement negotiations, diocesan officials did not press for details such as dates and allegations for every claim’ [Attorney Peter] Hutchins said. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it!’

“[N]o one will receive more than $500,000… but at the request of Hutchins’ clients, the diocese will not disclose their names, the details of the abuse or the amounts of individual settlements.”

Simultaneous to his positions and role in negotiating settlements in the Diocese, Rev. Edward J. Arsenault also served as Chairman of the Board of The National Catholic Risk Retention Group, an oversight conglomerate of insurance providers for a multitude of Catholic dioceses and institutions across the United States that covered the settlements.

Hypocrisy and a Double Life Unmasked

On April 23, 2014, Monsignor Arsenault was convicted in a plea deal that would prevent full public disclosure of the facts of his case and make them anything but transparent. The above handshake with his prosecutor became for some a symbol of the closed-door justice behind the deal.

Charged with embezzlement of $288,000 from the Diocese of Manchester and the estate of a deceased priest — funds used to groom and support a homosexual relationship with a young musician — Arsenault was sentenced to a prison term of four to twenty years. However someone had a vested interest in keeping Father MacRae from asking too many questions.

After a brief initial stay in the Concord prison receiving area, someone took the highly unusual step of arranging for Arsenault to be moved to a county jail to serve out his sentence. It was a move that some believe was orchestrated to prevent MacRae from learning anything about Arsenault’s handling of his own case.

Arsenault served only two years of his four-to-twenty year sentence before his prison term was commuted to home confinement. Somehow, even while in prison without income, his entire $288,000 restitution bill was paid in full. In February of 2019, Arsenault’s remaining twenty year sentence was mysteriously and quietly vacated and commuted. Many in the State and the Diocese of Manchester, though no one would go on the record, state their belief that Monsignor Arsenault received very special treatment in the Justice System. This was less true in the Church at higher levels. Before his sentence was terminated, Arsenault was dismissed from the clerical state by Pope Francis. Today, as “Mr. Arsenault,” he is managing a multimillion dollar contract for the City of New York.

Of interest, one of the charges against Monsignor Arsenault was that he had forged Bishop McCormack’s signature on travel and hotel vouchers for himself and his “guest” to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars. Arsenault also created and forged phony invoices from a psychologist for $15,000.

It seems that Arsenault developed his forgery technique directly from the case of Father MacRae. Between 2002 and 2005, Arsenault is alleged to have forged Bishop McCormack’s signature on official letters sent to MacRae in prison and on documents sent to the Vatican seeking canonical dismissal of Father MacRae from the priesthood. This commenced two to four years after Bishop McCormack stated his informed belief that MacRae is innocent and unjustly imprisoned.

It seems clear who Bishop McCormack’s “struggle” was with. It was in the interest of Arsenault’s ties and commitments with insurance companies that all claims against the diocese be settled. MacRae’s obstinacy in refusing to accept plea deals and settlements proved an obstacle that had to be removed. From 2001 to 2005, Father Arsenault carried out a pattern of misinformation to the Vatican and collusion with attorneys to summarily deprive the imprisoned priest of his rights to canonical, civil, and criminal due process. The manipulation against MacRae is its own scandal.

In 2002, Arsenault had Prisoner MacRae summoned to a prison office to engage him in a telephone conversation for a proffered deal. If MacRae would sever all communications with Dorothy Rabinowitz and The Wall Street Journal, Arsenault reportedly said, the diocese would retain counsel on his behalf for a new appeal.

Having just learned that all documentation sent to The Wall Street Journal was destroyed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, MacRae felt he had no other options. In March of 2002, Arsenault asked MacRae to send to his office all his defense files used at trial for the purpose of consultation with Attorney David Vicinanzo, a lawyer Arsenault claimed was retained to review MacRae’s case.

Six months later, MacRae learned that his legal files were never given to Attorney Vicinanzo, but were instead turned over to the NH Attorney General’s Office. Multiple letters to Arsenault and Attorney Vicinanzo for an explanation were never answered.

In January, 2003, MacRae was informed by other lawyers hired by Arsenault that a vast public release of files would take place as part of a diocese-wide settlement with the Attorney General in March of that year. MacRae was assured that he would be given a ten-day notice to review files in his regard and to challenge their release. Among all 73 priests on the list of the “credibly” accused newly published by Bishop Peter Libasci, MacRae was the only one never provided with the ten-day notice or any opportunity to review and challenge the release of his own privileged files.

Father MacRae’s letters of protest to Arsenault were never answered. His letter to Bishop McCormack resulted in a claim that the Attorney General issued a subpoena on the Diocese and walked off with priests’ files without regard for their source or for legal confidentiality.

In contrast, the Attorney General wrote to MacRae stating that, over the course of a week, the Diocese provided unfettered access to its files with no attempt at oversight. Further, the Attorney General wrote that all the files were reviewed as a result of a Grand Jury subpoena and were to remain confidential by law. However Bishop McCormack had signed a waiver surrendering the rights of all the priests involved. It is unclear, given the history above, who actually signed that waiver.

To their great credit, Vatican officials have not seen fit to move with a canonical process against this wrongly imprisoned priest. They have, however, administratively dismissed Monsignor Arsenault from the clerical state. He has since changed his name and is now known as Edward J. Bolognini.

To release a list of names of the accused today under the guise of transparency with Father Gordon MacRae identified solely as “convicted” is anything but transparent. It only further obscures this travesty of justice and turns it into just another kind of cover-up.

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Ryan A. MacDonald has published on the abuse crisis in multiple Catholic and secular publications. Please share this important post. You may also wish to read these related posts:

Grand Jury, St Paul’s School and the Diocese of Manchester

Bishop Peter A. Libasci Was Set Up by Governor Andrew Cuomo