“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

#MeToo and #HimToo: Jonathan Grover and Father Gordon MacRae

Jonathan Edward Grover died in Scottsdale Arizona just before his 49th birthday. His role in the case against Father Gordon MacRae leaves many unanswered questions.

Editor’s Note: The following is a guest post by independent writer Ryan A. MacDonald whose previous articles include “The Post-Trial Extortion of Father Gordon MacRae” and “A Grievous Error in Judge Joseph Laplante’s Court.”

When I read Father Gordon MacRae’s Holy Week post on These Stone Walls this year, I was struck by a revelation that he offered Mass in his prison cell for the soul of a man who helped put him there by falsely accusing him. I do not know that I could have done the same in his shoes, and even if I could, I am not so certain that I would. His post took a high road that most only strive for.

The unnamed subject of that post about Judas Iscariot was Jonathan Edward Grover who died in Arizona in February two weeks before his 49th birthday. An obituary indicated that he died “peacefully,” and cited ‘a “long career in the financial industry.” Police determined the cause of death to be an accidental overdose of self-injected opiates weeks after leaving rehab. In Arizona, he had charges for theft, criminal trespass, and multiple arrests for driving under the influence of drugs. A police report described him as “homeless.”

In the early 1990s, Jonathan Grover was one of Father MacRae’s accusers. MacRae first learned of Mr. Grover’s death from a letter written by a woman who had been a young adult friend of Grover at the time of MacRae’s trial in 1994. She wrote that she is now a social worker with “expertise in PTSD” (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). The letter accused MacRae of having “murdered” 48-year-old Grover. This requires a rational and factual response.

Of interest, Mr. Grover’s obituary – despite his being 48 years old at the time of death – featured his 1987 Keene High School (NH) graduation photograph when Grover was 18 years old. I had seen this photo before. It was among the discovery materials in MacRae’s defense files in preparation for his 1994 trial. The photograph raised the first of many doubts about Grover’s claims.

At age 18 in 1987, Grover gave Father Gordon MacRae, his parish priest and friend at the time, a nicely framed copy of that photo with a letter written on the back. It thanked MacRae for his “friendship and support,” and “for always being there for me.” It was a typically touching letter from a young man to someone he obviously admired. It was written before addiction and the inevitable justification of enablers took hold in his life.

Five years later, apparently forgetting that he ever wrote that letter, Jonathan Grover became the first of four adult brothers to accuse MacRae of a series of sexual assaults alleged to have occurred more than a decade earlier. So what happened between writing that letter in 1987 and accusing MacRae five years later in 1992? It is one of the burning questions left behind in this story.

The framed high school photograph and its accompanying letter never found their way into MacRae’s 1994 trial, or into the public record, because the trial dealt only with the claims of Jonathan’s brother, Thomas Grover. Jonathan was the first to accuse MacRae, but a trial on his claims was deferred. His story had many holes that did not reconcile with the facts. Investigators have since uncovered a different story from the one Grover and his brothers first told.

Bombshells and Black Ops

The two common denominators in the case against Father Gordon MacRae were expectations of money and James F. McLaughlin. In the 1980s, the city of Keene, New Hampshire, with a population then of about 26,000, employed a full-time sex crimes detective on its small police force. In 1988, McLaughlin launched investigations of at least three, and possibly more, Catholic priests in the area including Father Gordon MacRae.

His targeting of MacRae seems to have begun with a bizarre and explosive letter. In September 1988, Detective McLaughlin received a letter from Sylvia Gale, a social worker with the Division of Children, Youth and Families, the New Hampshire agency tasked with investigating child abuse. Ms. Gale’s letter to McLaughlin revealed that she had uncovered information about “a man in your area, a Catholic priest named Gordon MacRae.”

The letter described explosive information from an unnamed employee of Catholic Social Services in the Diocese of Manchester, who developed a slanderous tale that MacRae had been “a priest in Florida where he molested two boys, one of whom was murdered and his body mutilated.” The letter went on to claim that the case was still unsolved, and that MacRae was removed from Florida by Catholic Church officials to avoid that investigation.

The libelous letter also named a Church official, Monsignor John Quinn, as the source of this information reportedly told to an unnamed Church employee on the condition that she would be fired if she ever divulged it. The 1988 letter generated a secret 70-page report developed by Detective James McLaughlin. He launched a dogged pursuit of MacRae who was unaware at the time that any of this was going on.

This all began to unfold one year after Jonathan Grover graduated from Keene High School and presented Father MacRae with that framed photograph and letter of thanks. Armed with Sylvia Gale’s letter, Detective McLaughlin proceeded to question 26 Keene area adolescents and their parents who had known MacRae including members of the Grover family.

Up to that point, not one person had ever actually contacted McLaughlin with a complaint against MacRae, but rather it was McLaughlin who initiated these contacts. As reported below, some of them today claim to have been solicited by McLaughlin to accuse MacRae, some with the enticement of money.

I had to read up to page 54 of McLaughlin’s 1988 report before I came across any effort to corroborate the Florida “murder and mutilation” story with Florida law enforcement officials. By the time he learned that MacRae had never served as a priest in Florida and that no such crime had been committed there, the damage to MacRae’s reputation was already done, and the seeds were sown for the Grover brothers to ponder claims yet to come.

Among those approached by McLaughlin armed with Sylvia Gale’s slanderous letter was Mrs. Patricia Grover, Jonathan’s mother. A parishioner of Saint Bernard Parish in Keene where MacRae had served from 1983 to 1987, Mrs. Grover was also a DCYF social worker and an acquaintance of Sylvia Gale. She had previously worked with McLaughlin in the handling of other cases.

Mrs. Grover also knew Father MacRae. According to McLaughlin’s 1988 report, she was alarmed by the Sylvia Gale letter but doubted that MacRae had ever served as a priest in Florida. She nonetheless vowed to talk with her young adult sons about their relationship with MacRae. Four more years passed before the first of them, Jonathan Grover, accused him.

The “fake news” in the 1988 Sylvia Gale letter set this community abuzz with anxiety and gossip about the potentially lecherous and murderous priest in its midst. Later, Monsignor John Quinn and other Diocese of Manchester officials denied having any involvement in the untrue information about MacRae. They also denied that there was ever any priest who relocated from Florida to New Hampshire under the circumstances described.

Four years later in late 1992, Jonathan Grover became the first of four members of the Grover family to accuse Father Gordon MacRae of sexual abuse dating back to approximately the early 1980s. I use the word “approximately” because Grover and his brothers each presented highly conflicting and multiple versions of their stories and the relevant time frames.

As becomes clear below, Jonathan Grover’s claims became problematic for the prosecution of MacRae, but instead of questioning Grover’s veracity, the police detective engaged a contingency lawyer on Grover’s behalf. In a September 30, 1992 letter from McLaughlin to Jonathan Grover, the detective detailed his conversations with Keene attorney William Cleary who ultimately obtained a nearly $200,000 settlement for Grover from the Diocese of Manchester. From McLaughlin’s letter to Grover:

“As agreed, I contacted William Cleary about your case. Bill believes the statute of limitations has lapsed for a civil action, but this does not rule out the church being financially responsible Bill [Cleary] states he would like to meet with you for a conference. You would not be charged for this. Your options could then be outlined and discussed.”

There is reason to question Detective McLaughlin’s police reports in this case. In most of McLaughlin’s prior cases, he practiced a protocol of audio recording every interview with complainants. In many of his other reports that I have read, he made a point of explaining that he records interviews to protect the integrity of the investigation.

Two years prior to the Grover claims, for example, McLaughlin investigated a complaint against another former Keene area priest, Father Stephen Scruton. From the outset, his reports took pains to document his practice of securing both video and audio recordings of his interviews. He even administered a polygraph test on the accuser. All were standard protocol, but McLaughlin did not create a single recording of any type with any accuser in the case of Father Gordon MacRae. This is suspect, at best, and it has never been explained.

It is made more suspicious by the emergence of other information that has been developed by former FBI Special Agent Supervisor James Abbott who spent three years investigating the MacRae case. One of MacRae’s accusers, a high school classmate of Jonathan Grover, recanted his story when questioned by Mr. Abbott in 2008. An excerpt of Steven Wollschlager’s statement may shed light on why Detective McLaughlin chose not to record these interviews.

“In 1994 I was contacted by Keene Police Detective McLaughlin… I was aware at the time of Father MacRae’s trial knowing full well that it was bogus and having heard of the lawsuits and money involved and also the reputations of those who were making accusations… The lawsuits and money were of greatest discussion, and I was left feeling that if I would go along with the story I could reap the rewards as well. McLaughlin had me believing that all I had to do was make up a story about this priest and I could receive a large sum of money as others already had.

McLaughlin reminded me of the young child and girlfriend I had and referenced that life could go easier for us with a large amount of money… I was at the time using drugs and would have been influenced to say anything they wanted for money.”

In “The Trials of Father MacRae,” a 2013 article by Dorothy Rabinowitz in The Wall Street Journal, Detective McLaughlin described the above account simply as “a fabrication.” What struck me about Mr. Wollschlager’s statement, besides the fact that he had nothing whatsoever to gain by lying, is that he never went to Detective McLaughlin with an accusation. Instead, he alleges that it was McLaughlin who approached him, and the approach alleges the enticement of money.

Steven Wollschlager was not the first person to report such an overture. Given the nature of his account and others, it is unclear today whether Jonathan Grover and his brothers initiated their first contacts with this detective. This suspicion was a contentious issue in MacRae’s 1994 trial. Thomas Grover, the brother of Jonathan Grover, was asked under oath to reveal to whom he went first with his claims, the police or a personal injury lawyer, but he refused to answer. To this very day, that question has never been answered.

What became clear, however, is hard evidence that placed Detective James McLaughlin investigating at least some of this case, not from his office in the Keene Police Department, but from the Concord, NH office of Thomas Grover’s contingency lawyer, Robert Upton, before MacRae was even charged in the case.

A Conspiracy of Fraud

In a report labeled Case No. 93010850, Detective McLaughlin produced the first of several conflicting accounts of untaped interviews with Jonathan Grover. Note that the first two digits of McLaughlin’s report, “93,” seem to indicate the year it was typed, but the date on the report is August 27, 1992. The content of this report is sexually explicit so I will paraphrase. The report has Grover claiming that when he was 12 or 13 years old he “would spend nights in the St. Bernard rectory in Keene.” During those nights, he alleged, he was sexually assaulted by both Father Gordon MacRae and Father Stephen Scruton.

But there was an immediate problem. MacRae was never at St. Bernard’s Parish in Keene until being assigned there on June 15, 1983, when Grover was 14 years old. Father Stephen Scruton was never there before June of 1985 when Grover was 16 years old. These dates were easily determined from diocesan files, but McLaughlin never investigated this. The report continued with claims alleged to have taken place in the Keene YMCA hot tub:

“It was during these times that Grover would be seated in the whirlpool and both Father MacRae and Father Scruton would be joined in conversation and they would alternate in rubbing their foot against his genitals. Grover was unsure if the priests were acting in concert or if they were unaware of each other’s actions.”

This report is highly suspicious. Just months earlier, Detective McLaughlin had previously investigated Father Stephen Scruton for an identical claim brought by another person alleged to have occurred in 1985 after Scruton’s arrival at this parish. “Todd,” the person who brought that claim against Scruton, was also a high school classmate of Jonathan Grover.

After McLaughlin’s investigation, “Todd” obtained an undisclosed sum of money in settlement from the Diocese of Manchester. That interview with “Todd” was labeled Case No. 90035705 dated just 18 months before Jonathan Grover’s identical claims emerged. Unlike the Grover interviews, the interview with Todd was tape recorded by McLaughlin. Here is an excerpt from the report:

“Father Scruton was a regular at the YMCA. Todd went to the YMCA with Father Scruton. They decided to use the hot tub… At one point, Father Scruton took one of his feet and placed it between Todd’s legs and rubbed his genitals… The touching was intentional and not a mistake. A rubbing motion was used by Father Scruton… I asked Todd where he stood on civil lawsuits.”

It defies belief that a small town police detective could write a report about a Catholic priest (Scruton) fondling a teenager’s genitals in a YMCA hot tub, then 18 months later write virtually the same report with the same claims of doing the same things in the same place, only this time adding a second priest, but nothing in the second report seemed to even vaguely remind the detective of the first report.

After “Todd’s” YMCA hot tub complaint in 1990 — 18 months before Jon Grover’s own YMCA hot tub story — Father Stephen Scruton was charged by McLaughlin with misdemeanor sexual assault. He pled guilty and received a suspended sentence and probation. One year later, McLaughlin has someone else repeat the same story, only now involving both Scruton and MacRae, but two to four years before either of them was present in Keene.

What is most suspect about this claim of Jonathan Grover involving both priests is that in 1994, one year after writing the report, McLaughlin responded to a question under oath:

On occasion, I have had conversations with Reverend Stephen Scruton, however I have no recollection of ever discussing any actions of Gordon MacRae with the Reverend Scruton.

(Cited in USDC-NM 1504-JB)

But this all becomes more suspicious still. In the investigation file on these claims was found a transcript of a November 1988 Geraldo Rivera Show entitled “The Church’s Sexual Watergate.” It was faxed by the Geraldo Show in New York to Detective McLaughlin at the Keene Police Department two months after his 1988 receipt of the Sylvia Gale “Florida letter.” It was two years before “Todd’s” YMCA hot tub claim about Father Scruton and four years before Jonathan Grover’s claims. Here is an excerpt:

“Geraldo Rivera: What did the priest do to you Greg?

Greg Ridel: Around the age of 12 or so, he and I went to a YMCA. And I was an altar boy at the time. And the first time I was ever touched… he began stroking my penis in a hot tub, I believe it was, at a YMCA. From there it went to what you might call role playing in the rectory where the priests stay.”

Detective McLaughlin’s 1993 police report also had Jonathan Grover claiming that Father MacRae paid him money in the form of checks from his own and parish checking accounts in even amounts of $50 to $100 in order to maintain his silence about the abuse. McLaughlin never investigated this, but Father MacRae’s lawyer did investigate. Father MacRae’s personal checking account was researched from between 1979 to 1988. It revealed no checks issued to Jonathan or Thomas Grover.

However, the attorney uncovered several checks written from parish accounts to both Jonathan Grover and Thomas Grover. All were in even amounts between $40 and $100 and dated between 1985 and 1987 when these two brothers were 16 to 20 years of age respectively. The checks were filled out and signed by Rev. Stephen Scruton.

Days before Father Gordon MacRae’s 1994 trial commenced, his attorney sought Father Scruton for questioning. He declined to respond. When the lawyer sought a subpoena to force his deposition, Scruton fled the state. During trial, the jury heard none of this. Because the trial involved the shady claims of Thomas Grover alone, the defense could not introduce anything involving his brother, Jonathan.

In April, 2005, The Wall Street Journal published an extensive two-part investigation report of the Father MacRae case (“A Priest’s Story” Parts One and Two), but it omitted Father Stephen Scruton’s role in the story — perhaps because he could not be located. Diocese of Manchester officials reported for years that they had no awareness of Scruton’s whereabouts.

In November 2008, former FBI Special Agent Supervisor James Abbott was retained to investigate this case. He located Father Scruton at an address in Newburyport, Massachusetts just over the New Hampshire State Line. First reached by telephone, Scruton was reportedly agitated and nervous when he learned the reason for the call. The investigator heard a clear male voice in the background saying, “Steve if this is something that might help Gordon I think you should do it.” Scruton reluctantly agreed to meet.

The former FBI agent drove from his New York office to Newburyport, MA on the agreed-upon date and time, but Scruton refused to open the door. He said only that he had “consulted with someone” and now declines to answer any questions. The investigator then sent Scruton a summary of his involvement in this case and requested his cooperation by telling the simple truth.

Days after receiving it, Stephen Scruton suffered a mysterious fall down a flight of stairs and never regained consciousness. Father Stephen Scruton died a month later in January of 2009. He took the truth with him, and now Jonathan Grover has done the same. But facts speak a truth of their own. Readers can today form their own conclusions about this story.

I have formed mine, and I remain more than ever convinced that an innocent man is in prison in New Hampshire, a blight on the American justice system. Having thus far served 24 years of wrongful imprisonment for crimes that never took place, Father Gordon MacRae still prays for the dead.

“After three years of investigation of this case, I have found no evidence that Father MacRae committed these crimes, or any crimes.”

Editor’s Note: Please share this post which could be of great importance to Father MacRae for justice in both Church and State.

Ryan A. MacDonald has published extensively in both print and online media. Ryan’s articles include:

The Trial of Father MacRae: A Conspiracy of Fraud

How Psychotherapists Helped Send an Innocent Priest to Prison

In the Fr Gordon MacRae Case, Whack-a-Mole Justice Holds Court

Justice and a Priest’s Right of Defense in the Diocese of Manchester

The Trial of Father MacRae: A Conspiracy of Fraud

For Catholic priests, merely being accused is now evidence of guilt. A closer look at the prosecution of Fr Gordon MacRae opens a window onto a grave injustice.

Former Judge Arthur Brennan

Arrested at a Washington, DC protest in 2011

For Catholic priests, merely being accused is now evidence of guilt. A closer look at the prosecution of Fr. Gordon MacRae opens a window onto a grave injustice.

Editor’s Note: This is Part 1 of a two-part guest post by Ryan A. MacDonald.

“Those aware of the facts of this case find it hard to imagine that any court today would ignore the perversion of justice it represents.”

The above quote says it all. I wrote for These Stone Walls two weeks ago to announce a new federal appeal filed in the Father Gordon MacRae case. I mentioned my hope to write in more detail about the perversion of justice cited by Dorothy Rabinowitz in “The Trials of Father MacRae,” her third major article on the MacRae case in The Wall Street Journal.

The details of how such injustice is perpetrated are especially important in cases like Father MacRae’s because there was no evidence of guilt — not one scintilla of evidence — presented to the jury in his 1994 trial. I recently wrote “Justice and a Priest’s Right of Defense in the Diocese of Manchester,” an article with photographs of the exact location where the charges against this priest were claimed to have occurred. If you read it, you can judge for yourself whether those charges were even plausible.

The sexual assaults for which Father Gordon MacRae has served two decades in prison were to have taken place five times in as many weeks, all in the light of day in one of the busiest places in downtown Keene, New Hampshire. Yet no one saw anything. No one heard anything. Accuser Thomas Grover — almost age 16 when he says it happened, and age 26 when he first accused the priest — testified that he returned from week to week after each assault because he repressed the memory of it all while having a weekly “out-of-body experience.”

The complete absence of evidence in the case might have posed a challenge for the prosecution if not for a pervasive climate of accusation, suspicion, and greed. It was the climate alone that convicted this priest, that and a press release from the Diocese of Manchester that declared him guilty before his trial commenced. As Dorothy Rabinowitz wrote,

“Diocesan officials had evidently found it inconvenient to dally while due process took its course.”

It was 1994, the onset of fear and loathing when many New England priests were accused, when the news media focused its sights on Catholic scandal, when lawyers and insurance companies for bishops and dioceses urged as much distance as possible from the accused while quiet settlements mediated from behind closed doors doled out millions to accusers and their lawyers. Accusation alone became all the evidence needed to convict a priest, and in Keene, New Hampshire — according to some who were in their teens and twenties then — word got out that accusing a priest was like winning the lottery.

The fact that little Keene, NH — a town of about 22,000 in 1994 — had a full time sex crimes detective on its police force of 30 brought an eager ace crusader into the deck stacking against Gordon MacRae. By the time of the 1994 trial, Detective James F. McLaughlin boasted of having found more than 1,000 victims of sexual abuse in 750 cases in Keene. The concept that someone might be falsely accused escaped him completely. He reportedly once told Father MacRae, “I have to believe my victims.” This priest WAS one of his victims.

The only “hard evidence” placed before the MacRae jury was a document proving that he is in fact an ordained Catholic priest. The prosecution was aided much by an outrageous statement from Judge Arthur Brennan instructing jurors to disregard inconsistencies in Thomas Grover’s testimony. This is no exaggeration. As Dorothy Rabinowitz wrote, those jurors “had much to disregard.”

It is important to unravel the facts of this prosecution, not all of which could appear in the current appeal briefs. I have done some of this unraveling in an article entitled, “In the Fr Gordon MacRae Case, Whack-A-Mole Justice Holds Court.” I consider it an important article because it addresses head-on many of the distortions put forth by those committed to keeping the momentum against priests and the Church going. This is a lucrative business, after all. Most importantly, that article exposes the “serial victims” behind MacRae’s prosecution.

Seduced and Betrayed

Had I been a member of the jury that convicted Father MacRae, I would no doubt feel betrayed today to learn that Thomas Grover, a sole accuser at trial, accused so many men of sexual abuse “that he appeared to be going for some sort of sexual abuse victim world record” according to Grover’s counselor, Ms. Debbie Collett. That fact was kept from the jury, and if any one was seduced in this case, it was the jurors themselves.

Ms. Collett reports today that Grover accused many — including his adoptive father — during therapy sessions with her in the late 1980s, but never accused MacRae. Ms. Collett also reports today that she was herself “badgered, coerced, and threatened” by Detective McLaughlin and another Keene police officer into altering her testimony and withholding the truth about Thomas Grover’s other past abuse claims from the jury. If the justice system does not take seriously her statement about pre-trial coercion, it undermines the very foundations of due process.

I subscribe to The Wall Street Journal’s weekly “Law Blog” entries in its online edition. A recent posting was by a high-profile corporate lawyer who occasionally undertakes appeals for wrongfully convicted criminal defendants. After winning the freedom of one unjustly imprisoned man who served 15 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, the lawyer wrote that justice has a greater hope of prevailing in such a case when a layman with no training in the law can read the legal briefs in an appeal and conclude beyond a doubt that an injustice has indeed taken place.

This was exactly my reaction after reading Attorney Robert Rosenthal’s federal appeal brief filed on behalf of Father MacRae. I have heard of similar reactions from others. One reader recently wrote, “I just read the appeal brief and I’m stunned! How was this man ever convicted in a US court of law?” Another reader wrote, “Taken as a whole, the MacRae trial was a serious breach of American justice and decency. Had I been a juror, I would today feel betrayed and angry by what I have just learned.”

A few weeks ago in his post on These Stone Walls, Father MacRae wrote of how justice itself was a victim in the prosecution of Monsignor William Lynn in a Philadelphia courtroom. That conviction was recently reversed by an appeals court in a ruling that described that trial and conviction as “fundamentally flawed.” In his appeal of Father MacRae’s trial, Attorney Robert Rosenthal has masterfully demonstrated the fundamental flaws that brought about the prosecution of MacRae and the verdict that sent him to prison. Taken as a whole, no competent person could conclude from those pleadings that the conviction against this priest should stand.

Psychotherapist for the Prosecution

I would like to seize upon a few of the details, and magnify them to demonstrate just how very flawed this trial was. I’ll begin with some excerpts from a document I recently obtained in this case. It is a letter written by an observer at Father MacRae’s 1994 trial.

The letter, dated October 30, 2013, was addressed to retired judge Arthur Brennan who presided over the trial of Father MacRae and who sentenced him to a prison term of 67 years. The letter was written by a man whose career was in the news media, a fact that very much influenced his attention to detail throughout the trial of Father MacRae. The letter writer expressed to the retired judge that he held his pen for so many years, but now that state courts are no longer involved in this appeal, he felt more free to write. Here is a portion of that letter:

“We saw something in your courtroom during the MacRae trial that I don’t think you ever saw. My wife nudged me and pointed to a woman, Ms. Pauline Goupil, who was engaged in what appeared to be clear witness tampering. During questioning by the defense attorney, Thomas Grover seemed to feel trapped a few times. On some of those occasions, we witnessed Pauline Goupil make a distinct sad expression with a downturned mouth and gesturing her finger from the corner of her eye down her cheek at which point Mr. Grover would begin to cry and sob.”

Pauline Goupil was called under oath to the witness stand in the 1994 trial where she produced a bare bones treatment file of Thomas Grover that contained little, if any, information about claims against Father MacRae. She stated under oath that this was her entire file.

Two years later, Ms. Goupil testified in an evidentiary hearing about the lawsuits brought by Thomas Grover and three of his brothers against Father MacRae and the Diocese of Manchester. Under oath in that hearing, Pauline Goupil referenced an extensive file with many notations about claims against Father MacRae and about how she helped Thomas Grover to “remember” the details of his claims. In one of these two testimonies under oath — or perhaps in both — Pauline Goupil appears to have committed perjury.

In a brief, defensive hand-written reply to the above letter from the unnamed trial observer, retired Judge Brennan referred to the testimony of “young Thomas Grover” at the MacRae trial. This spoke volumes about that judge’s view of this case. The “young Thomas Grover” on the witness stand in Judge Brennan’s court was a 5’ 11” 220-lb., 27-year-old man with a criminal record of assault, forgery, drug, burglary, and theft charges. Prior to the trial, he was charged with beating his ex-wife. “He broke my nose,” she says today. The charge was dropped after MacRae’s trial. Once again, from the observer’s letter to the retired judge:

“Secondly, I was struck by the difference in Thomas Grover’s demeanor on the witness stand in your court and his demeanor just moments before and after outside the courtroom. On the stand he wept and appeared to be a vulnerable victim. Moments later, during court recess, in the parking lot he was loud, boisterous and aggressive. One time he even confronted me in a threatening attempt to alter my own testimony during sentencing.”

And lest we forget, the sentence of 67 years was imposed by Judge Arthur Brennan after Father MacRae three times refused a prosecution plea deal to serve only one to three years in exchange for an admission of guilt. It is one of the ironic challenges to justice in this case that had Father MacRae been actually guilty, he would have been released from prison 17 years ago.

Like others involved in this trial, Ms. Pauline Goupil was contacted by retired FBI Special Agent James Abbott who conducted an investigation of the case over the last few years. Ms. Goupil refused to be interviewed or to answer any questions.

Thomas Grover, today taking refuge on a Native American reservation in Arizona, also refused to answer questions when found by Investigator James Abbott. He reportedly did not present as someone victimized by a parish priest, but rather as someone caught in a monumental lie. “I want a lawyer!” was all he would say. We all watch TV’s “Law and Order.” We all know what “I want a lawyer” means.

Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Christians.

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Salvation.

“All who see me scoff at me. They mock me with parted lips; they wag their heads.”

During Holy Week one year, I wrote “Simon of Cyrene, the Scandal of the Cross, and Some Life Sight News.” It was about the man recruited by Roman soldiers to help carry the Cross of Christ. I have always been fascinated by Simon of Cyrene, but truth be told, I have no doubt that I would react with his same spontaneous revulsion if fate had me walking in his sandals that day past Mount Calvary.

Some BTSW readers might wish for a different version, but I cannot write that I would have heroically thrust the Cross of Christ upon my own back. Please rid yourselves of any such delusion. Like most of you, I have had to be dragged kicking and screaming into just about every grace I have ever endured. The only hero at Calvary was Christ. The only person worth following up that hill — up ANY hill — is Christ. I follow Him with the same burdens and trepidation and thorns in my side as you do. So don’t follow me. Follow Him.

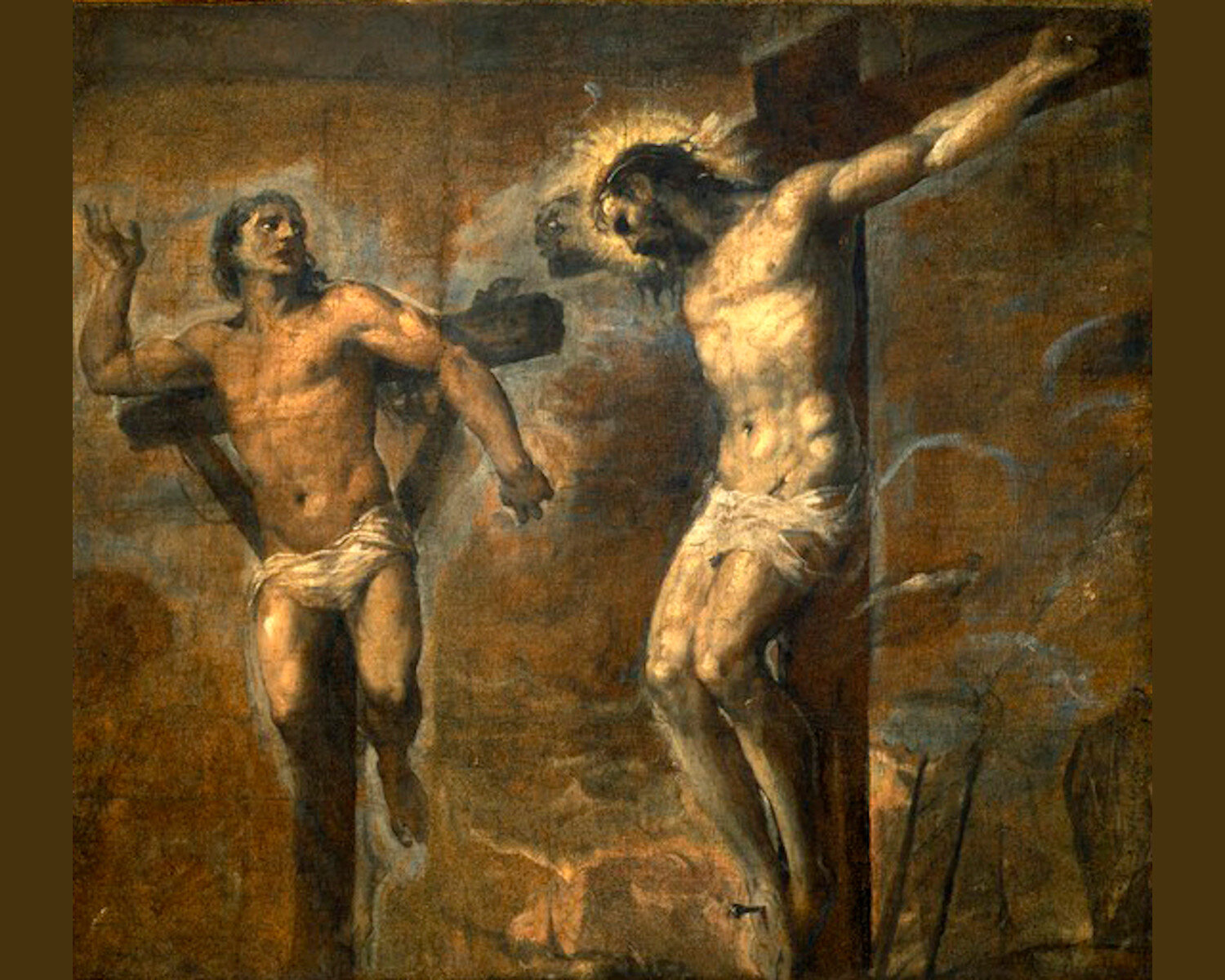

This Holy Week, one of many behind these stone walls, has caused me to use a wider angle lens as I examine the events of that day on Mount Calvary as the Evangelists described them. This year, it is Dismas who stands out. Dismas is the name tradition gives to the man crucified to the right of the Lord, and upon whom is bestowed a dubious title: the “Good Thief.”

As I pondered the plight of Dismas at Calvary, my mind rolled some old footage, an instant replay of the day I was sent to prison — the day I felt the least priestly of all the days of my priesthood.

It was the mocking that was the worst. Upon my arrival at prison after trial late in 1994, I was fingerprinted, photographed, stripped naked, showered, and unceremoniously deloused. I didn’t bother worrying about what the food might be like, or whether I could ever sleep in such a place. I was worried only about being mocked, but there was no escaping it. As I was led from place to place in chains and restraints, my few belongings and bedding stuffed into a plastic trash bag dragged along behind me, I was greeted by a foot-stomping chant of prisoners prepped for my arrival: “Kill the priest! Kill the priest! Kill the priest!” It went on into the night. It was maddening.

It’s odd that I also remember being conscious, on that first day, of the plight of the two prisoners who had the misfortune of being sentenced on the same day I was. They are long gone now, sentenced back then to just a few years in prison. But I remember the walk from the courthouse in Keene, New Hampshire to a prison-bound van, being led in chains and restraints on the “perp-walk” past rolling news cameras. A microphone was shoved in my face: “Did you do it, Father? Are you guilty?”

You may have even witnessed some of that scene as the news footage was recently hauled out of mothballs for a WMUR-TV news clip about my new appeal. Quickly led toward the van back then, I tripped on the first step and started to fall, but the strong hands of two guards on my chains dragged me to my feet again. I climbed into the van, into an empty middle seat, and felt a pang of sorrow for the other two convicted criminals — one in the seat in front of me, and the other behind.

“Just my %¢$#@*& luck!” the one in front scowled as the cameras snapped a few shots through the van windows. I heard a groan from the one behind as he realized he might vicariously make the evening news. “No talking!” barked a guard as the van rolled off for the 90 minute ride to prison. I never saw those two men again, but as we were led through the prison door, the one behind me muttered something barely audible: “Be strong, Father.”

Revolutionary Outlaws

It was the last gesture of consolation I would hear for a long, long time. It was the last time I heard my priesthood referred to with anything but contempt for years to come. Still, to this very day, it is not Christ with whom I identify at Calvary, but Simon of Cyrene. As I wrote in “Simon of Cyrene and the Scandal of the Cross“:

“That man, Simon, is me . . . I have tried to be an Alter Christus, as priesthood requires, but on our shared road to Calvary, I relate far more to Simon of Cyrene. I pick up my own crosses reluctantly, with resentment at first, and I have to walk behind Christ for a long, long time before anything in me compels me to carry willingly what fate has saddled me with . . . I long ago had to settle for emulating Simon of Cyrene, compelled to bear the Cross in Christ’s shadow.”

So though we never hear from Simon of Cyrene again once his deed is done, I’m going to imagine that he remained there. He must have, really. How could he have willingly left? I’m going to imagine that he remained there and heard the exchange between Christ and the criminals crucified to His left and His right, and took comfort in what he heard. I heard Dismas in the young man who whispered “Be strong, Father.” But I heard him with the ears of Simon of Cyrene.

Like a Thief in the Night

Like the Magi I wrote of in “Upon a Midnight Not So Clear,” the name tradition gives to the Penitent Thief appears nowhere in Sacred Scripture. Dismas is named in a Fourth Century apocryphal manuscript called the “Acts of Pilate.” The text is similar to, and likely borrowed from, Saint Luke’s Gospel:

“And one of the robbers who were hanged, by name Gestas, said to him: ‘If you are the Christ, free yourself and us.’ And Dismas rebuked him, saying: ‘Do you not even fear God, who is in this condemnation? For we justly and deservedly received these things we endure, but he has done no evil.’”

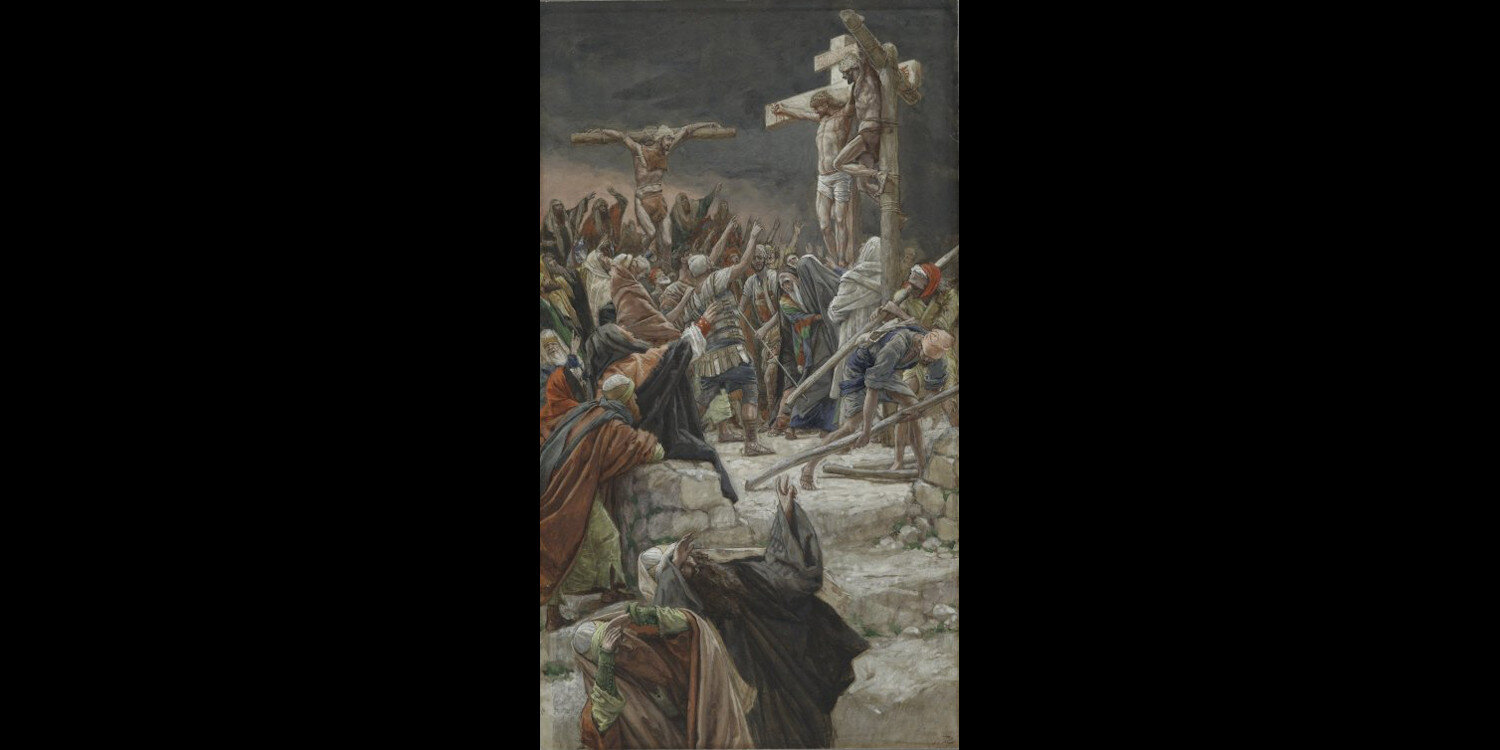

What the Evangelists tell us of those crucified with Christ is limited. In Saint Matthew’s Gospel (27:38) the two men are simply “thieves.” In Saint Mark’s Gospel (15:27), they are also thieves, and all four Gospels describe their being crucified “one on the left and one on the right” of Jesus. Saint Mark also links them to Barabbas, guilty of murder and insurrection. The Gospel of Saint John does the same, but also identifies Barabbas as a robber. The Greek word used to identify the two thieves crucified with Jesus is a broader term than just “thief.” Its meaning would be more akin to “plunderer,” part of a roving band caught and given a death penalty under Roman law.

Only Saint Luke’s Gospel infers that the two thieves might have been a part of the Way of the Cross in which Saint Luke includes others: Simon of Cyrene carrying Jesus’ cross, and some women with whom Jesus spoke along the way. We are left to wonder what the two criminals witnessed, what interaction Simon of Cyrene might have had with them, and what they deduced from Simon being drafted to help carry the Cross of a scourged and vilified Christ.

In all of the Gospel presentations of events at Golgotha, Jesus was mocked. It is likely that he was at first mocked by both men to be crucified with him as the Gospel of St. Mark describes. But Saint Luke carefully portrays the change of heart within Dismas in his own final hour. The sense is that Dismas had no quibble with the Roman justice that had befallen him. It seems no more than what he always expected if caught:

“One of the criminals who were hanged railed at him, saying, ‘Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!’ But the other rebuked him, saying, ‘Do you not fear God since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed justly, for we are receiving the due reward of our deeds; but this man has done nothing wrong.’ ”

The Flight into Egypt

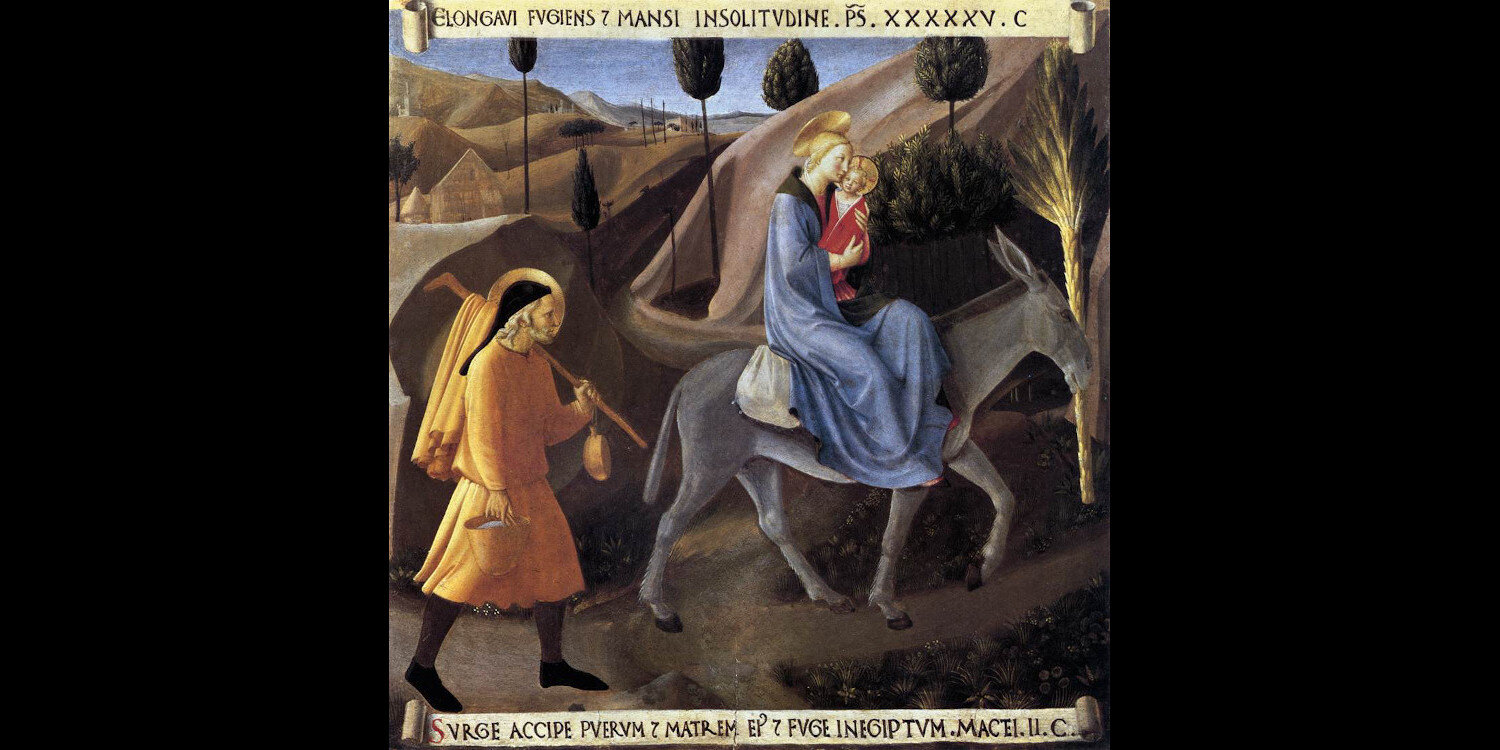

The name, “Dismas” comes from the Greek for either “sunset” or “death.” In an unsubstantiated legend that circulated in the Middle Ages, in a document known as the “Arabic Gospel of the Infancy,” this encounter from atop Calvary was not the first Gestas and Dismas had with Jesus. In the legend, they were a part of a band of robbers who held up the Holy Family during the Flight into Egypt after the Magi departed in Saint Matthews Gospel (Matthew 2:13-15).

This legendary encounter in the Egyptian desert is also mentioned by Saint Augustine and Saint John Chrysostom who, having heard the same legend, described Dismas as a desert nomad, guilty of many crimes including the crime of fratricide, the murder of his own brother. This particular part of the legend, as you will see below, may have great symbolic meaning for salvation history.

In the legend, Saint Joseph, warned away from Herod by an angel (Matthew 2:13-15), opted for the danger posed by brigands over the danger posed by Herod’s pursuit. Fleeing with Mary and the child into the desert toward Egypt, they were confronted by a band of robbers led by Gestas and a young Dismas. The Holy Family looked like an unlikely target having fled in a hurry, and with very few possessions. When the robbers searched them, however, they were astonished to find expensive gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh — the Gifts of the Magi. However, in the legend Dismas was deeply affected by the infant, and stopped the robbery by offering a bribe to Gestas. Upon departing, the young Dismas was reported to have said:

“0 most blessed of children, if ever a time should come when I should crave thy mercy, remember me and forget not what has passed this day.”

Paradise Found

The most fascinating part of the exchange between Jesus and Dismas from their respective crosses in Saint Luke’s Gospel is an echo of that legendary exchange in the desert 33 years earlier — or perhaps the other way around:

“‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingly power.’ And he said to him, ‘Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.’”

The word, “Paradise” used by Saint Luke is the Persian word, “Paradeisos” rarely used in Greek. It appears only three times in the New Testament. The first is that statement of Jesus to Dismas from the Cross in Luke 23:43. The second is in Saint Paul’s description of the place he was taken to momentarily in his conversion experience in Second Corinthians 12:3 — which I described in “The Conversion of Saint Paul and the Cost of Discipleship.” The third is the heavenly paradise that awaits the souls of the just in the Book of Revelation (2:7).

In the Old Testament, the word “Paradeisos” appears only in descriptions of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:8, and in the banishment of Cain after the murder of his brother, Abel:

“Cain left the presence of the Lord and wandered in the Land of Nod, East of Eden.”

Elsewhere, the word appears only in the prophets (Isaiah 51:3 and Ezekiel 36:35) as they foretold a messianic return one day to the blissful conditions of Eden — to the condition restored when God issues a pardon to man.

If the Genesis story of Cain being banished to wander “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden” is the symbolic beginning of our human alienation from God — the banishment from Eden marking an end to the State of Grace and Paradise Lost — then the Dismas profession of faith in Christ’s mercy is symbolic of Eden restored — Paradise Regained.

From the Cross, Jesus promised Dismas both a return to spiritual Eden and a restoration of the condition of spiritual adoption that existed before the Fall of Man. It’s easy to see why legends spread by the Church Fathers involved Dismas guilty of the crime of fratricide just as was Cain.

A portion of the cross upon which Dismas is said to have died alongside Christ is preserved at the Church of Santa Croce in Rome. It’s one of the Church’s most treasured relics. Catholic apologist, Jim Blackburn has proposed an intriguing twist on the exchange on the Cross between Christ and Saint Dismas. In “Dismissing the Dismas Case,” an article in the superb Catholic Answers Magazine Jim Blackburn reminded me that the Greek in which Saint Luke’s Gospel was written contains no punctuation. Punctuation had to be added in translation. Traditionally, we understand Christ’s statement to the man on the cross to his right to be:

“Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

The sentence has been used by some non-Catholics (and a few Catholics) to discount a Scriptural basis for Purgatory. How could Purgatory be as necessary as I described it to be in “The Holy Longing” when even a notorious criminal is given immediate admission to Paradise? Ever the insightful thinker, Jim Blackburn proposed a simple replacement of the comma giving the verse an entirely different meaning:

“Truly I say to you today, you will be with me in Paradise.”

Whatever the timeline, the essential point could not be clearer. The door to Divine Mercy was opened by the events of that day, and the man crucified to the right of the Lord, by a simple act of faith and repentance and reliance on Divine Mercy, was shown a glimpse of Paradise Regained.

The gift of Paradise Regained left the cross of Dismas on Mount Calvary. It leaves all of our crosses there. Just as Cain set in motion our wandering “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden,” Dismas was given a new view from his cross, a view beyond death, away from the East of Eden, across the Undiscovered Country, toward eternal home.

Saint Dismas, pray for us.