The Sign of the Cross: Saint Maximilian Kolbe's Gift of Life

Editor's Note: This is Part Two of a two-part post. Part One was entitled "Suffering and St Maximilian Kolbe Behind These Stone Walls."Writing from England in a recent posting at the venerable Homiletic and Pastoral Review, Psychologist Brent Withers has an intriguing article entitled, "The Science of Divine Love" (July 18, 2013). It is about the means for our sanctification and it describes how our actions, sacrifices and sufferings "build up the mystical body of Christ." It's a concept at the very heart of St. Maximilian's sacrifice of his life at Auschwitz, a sacrifice that gave life to another as described last week in Part One of this post. It is a concept central to the Gospel:

Editor's Note: This is Part Two of a two-part post. Part One was entitled "Suffering and St Maximilian Kolbe Behind These Stone Walls."Writing from England in a recent posting at the venerable Homiletic and Pastoral Review, Psychologist Brent Withers has an intriguing article entitled, "The Science of Divine Love" (July 18, 2013). It is about the means for our sanctification and it describes how our actions, sacrifices and sufferings "build up the mystical body of Christ." It's a concept at the very heart of St. Maximilian's sacrifice of his life at Auschwitz, a sacrifice that gave life to another as described last week in Part One of this post. It is a concept central to the Gospel:

"This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends." (John 15: 13)

Among his many examples of how suffering can become sacrifice, Brent Withers wrote of the "practice of non-resistance" in the spiritual life of St. Therese of Lisieux who invites us "to receive hardships warmly." Those who survived the horrors of Auschwitz to tell of the demeanor of St. Maximilian describe a man who in life and in death lived that tenet of the Gospel. The Jewish psychiatrist, Viktor Frankl, described the power of such sacrifice in his masterful work about physical, mental, and spiritual survival of Auschwitz, Man's Search for Meaning (Beacon Press, 1992):

"We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms - to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's way." (p. 75)

These very words opened my eyes and my soul to a better path than the usual bitterness and resentment that consumes prisoners and transforms prison from Purgatory to hell. Not to be bitter, not to swallow the toxic pill of resentment, not to wear hurt and anger like a shield are a personal choice. Viktor Frankl himself used the example of Maximilian Kolbe at Auschwitz as a model for the inspiration to survive that he found in prison. It was the conclusion of Man's Search for Meaning and the heart of TSW's "The Paradox of Suffering: An Invitation from Saint Maximilian Kolbe."

“Sigmund Freud once asserted, ‘Let one attempt to expose a number of the most diverse people uniformly to hunger. With the increase of the imperative urge of hunger all individual differences will blur, and in their stead will appear the uniform expression of the one unstilled urge.’ Thank heaven Sigmund Freud was spared knowing the concentration camps from the inside… Think of Father Maximilian Kolbe who was starved and finally murdered by an injection of carbolic acid at Auschwitz and who in 1983 was canonized.” (p. 153-154)

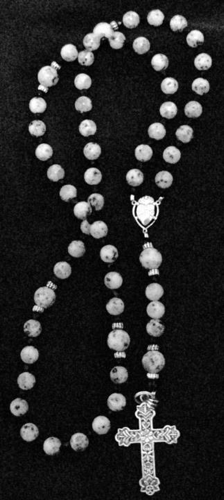

This image of prison as Purgatory came to me also this month through TSW reader, Kathleen Riney. Kathleen creates rosaries and chaplets upon request from those who might want to have one specially made. She names all the rosaries she creates, sometimes without even knowing why she chooses a specific name, or a specific material. What she creates are really works of art, spiritual treasures of immense beauty.Months ago, I received a message from Kathleen. She had created a rosary that she had named "Purgatory" and after creating it she decided that she must send it to me. It took many months, but on the same day I read "The Science of Divine Love" by Brent Withers about offering suffering to help free souls from Purgatory, Kathleen Riney's "Purgatory" rosary arrived.Words cannot describe this religious object, and its photograph cannot do it justice. I had never owned something so starkly beautiful and yet so powerful in its essence. It is constructed of 8mm Sesame Jasper stones that Kathleen wrote "for some reason reminded me of Purgatory," and she was absolutely right. It is magnificent, and designed for a singular purpose: to give meaning to the suffering of prison, and to offer it for abandoned souls. It is a sacred duty.ROSES AND THORNSBut before I describe how St. Maximilian has defined that duty, I want to describe a thorn in my side left by a rose from St. Therese of Lisieux. In "A Shower of Roses," an early post on These Stone Walls, I wrote of a day when I turned to St. Therese to take the hand of a young friend at the moment of her death. That post described two encounters with this Saint known as "The Little Flower" that, viewed only through the lens of pragmatism, could easily be explained away. When viewed through a lens of faith, however, those simple encounters with a rose from St. Therese were a spiritual earthquake.In time, however, as with all such experiences for the weak of faith, this encounter with a rose from St. Therese gave way to my ongoing human struggle with all of life's thorns. It's nice to admire saints from a safe distance, but when they choose us to be our patrons it is not to admire them, but to emulate them.I'm thankful I was chosen by St. Maximilian and not St. Therese, though I admire her greatly. Practicing non-resistance to frustrations and hardship seemed to come natural for her, though I'm sure that if this were true she would not have needed so much practice. I, on the other hand, spend much of my life in a knot of irritation over the daily hardships and humiliations that are the nature of prison. Brent Withers wrote of how the practice of receiving hardships with non-resistance was a way of living daily life for St. Therese. A sister washing the convents dirty handkerchiefs with zeal accidentally splashed the fouled water into the face of St. Therese - who not only remained silent, but would not even step away to avoid it.In life, St. Therese made it her daily practice to not only not react in anger or frustration in the face of hardship and annoyances, but to also do nothing to avoid them or ward them off, accepting each such moment as a small share in the Cross of Christ. I share her love of the Cross, and even her wish to bear it in sacrifice, but like so many of you I sure do struggle with her daily example of living it in the face of annoyance.Last Sunday afternoon, for example, I had just finished typing the last page of Part One of this two-part post. I sat down with a pencil to proofread it when my young friend, Ralph Carey came rushing into my cell. I mentioned Ralph months ago in "Les Miserables: The Bishop and the Redemption of Jean Valjean" which has a few parallels with his life. Always like an accident going someplace to happen, Ralph plopped down a book in front of me to ask for the meaning of a word, and knocked over my just-poured cup of coffee ruining beyond salvation the post I had just spent hours typing. It's amazing how the volume of a cup of coffee expands exponentially when outside the cup. It was everywhere."Oops! My bad!" he said, "But at least none got on my book!" What I was thinking was not exactly the practice of non-resistance to hardship lived daily by St. Therese. What I was thinking cannot be printed on a respectable Catholic blog.To be fair to myself, I did not explode at Ralph. He would have been very hurt had I done so, and so for the sake of that I contained my frustration. Instead of exploding, I let him make me another cup of coffee - then asked him to set it down at least ten feet away from me while I set up my typewriter for round two.In his HPR article, Brent Withers went on to suggest that experiences of frustration and hardship should be spontaneously offered for the souls in Purgatory who are forgotten and unnoticed. And not only should the hardship be so offered, says the writer, but also the sin which follows - the impatience and frustration and anger that wells up in response to such events. When I read this, I had an immediate image in my mind that if I offer all the moments of impatience, frustration and anger that prison brings to me, I might cause a veritable stampede out of Purgatory.THE CHALLENGE OF SAINT MAXIMILIANI know many of you have read Pornchai Moontri's guest post on These Stone Walls last year entitled, "The Duty of a Knight: To Dream the Impossible Dream." In powerful words, Pornchai wrote of his own spiritual journey and of how St. Maximilian insinuated himself into Pornchai's life almost perfectly parallel to the ways he came to me.I remember the day Pornchai and I landed in the same cell. We had already been friends for a year or so when both our cellmates were suddenly moved to another place. Prisoners here have no say where they will live and with whom. The next day, I was moved into the cell with Pornchai. He had been away working in the wood carving shop as I moved in. Later that day when he came into the cell, he saw the image of St. Maximilian above the shaving mirror near the cell door as described in Part One of this post. Pornchai stared at it closely, and to my surprise he asked, "Is this you?""Far from it," I said. I then told Pornchai the story of St. Maximilian, of what he did at Auschwitz, of his canonization by Pope John Paul II in 1982 as a Martyr of Charity just months after I was ordained, and of how and why his image came to be above my mirror all of which I described last week.Pornchai took this all in with an intensity and focus I had never seen in him before. In the months to follow, other prisoners stopped at our cell, and when they asked about the man above the mirror, Pornchai told them the story of St. Maximilian. I saw taking place within him the very transformation that Maximilian brought about in me - an awareness that the events in my life may not be all about me, that some higher purpose is at work, and that I have a choice. I can choose the triumph of injustice. I can be its victim, bitter and resentful, while I passively implore my Patron Saint's intercession to be delivered from it all. Or I can choose to emulate him, to be like the prisoner-priest above my mirror.I first became aware of the spiritual dialogue between St. Maximilian and Pornchai, however, when the latter started talking about designing a ship that he wanted to name for his new Patron Saint. I described Pornchai's great skill at woodcraft in "Come Sail Away! Pornchai Moontri and the Art of Model Shipbuilding." Over the succeeding weeks, Pornchai showed me drawings of his design for the St. Maximilian with its planned black hull.

This image of prison as Purgatory came to me also this month through TSW reader, Kathleen Riney. Kathleen creates rosaries and chaplets upon request from those who might want to have one specially made. She names all the rosaries she creates, sometimes without even knowing why she chooses a specific name, or a specific material. What she creates are really works of art, spiritual treasures of immense beauty.Months ago, I received a message from Kathleen. She had created a rosary that she had named "Purgatory" and after creating it she decided that she must send it to me. It took many months, but on the same day I read "The Science of Divine Love" by Brent Withers about offering suffering to help free souls from Purgatory, Kathleen Riney's "Purgatory" rosary arrived.Words cannot describe this religious object, and its photograph cannot do it justice. I had never owned something so starkly beautiful and yet so powerful in its essence. It is constructed of 8mm Sesame Jasper stones that Kathleen wrote "for some reason reminded me of Purgatory," and she was absolutely right. It is magnificent, and designed for a singular purpose: to give meaning to the suffering of prison, and to offer it for abandoned souls. It is a sacred duty.ROSES AND THORNSBut before I describe how St. Maximilian has defined that duty, I want to describe a thorn in my side left by a rose from St. Therese of Lisieux. In "A Shower of Roses," an early post on These Stone Walls, I wrote of a day when I turned to St. Therese to take the hand of a young friend at the moment of her death. That post described two encounters with this Saint known as "The Little Flower" that, viewed only through the lens of pragmatism, could easily be explained away. When viewed through a lens of faith, however, those simple encounters with a rose from St. Therese were a spiritual earthquake.In time, however, as with all such experiences for the weak of faith, this encounter with a rose from St. Therese gave way to my ongoing human struggle with all of life's thorns. It's nice to admire saints from a safe distance, but when they choose us to be our patrons it is not to admire them, but to emulate them.I'm thankful I was chosen by St. Maximilian and not St. Therese, though I admire her greatly. Practicing non-resistance to frustrations and hardship seemed to come natural for her, though I'm sure that if this were true she would not have needed so much practice. I, on the other hand, spend much of my life in a knot of irritation over the daily hardships and humiliations that are the nature of prison. Brent Withers wrote of how the practice of receiving hardships with non-resistance was a way of living daily life for St. Therese. A sister washing the convents dirty handkerchiefs with zeal accidentally splashed the fouled water into the face of St. Therese - who not only remained silent, but would not even step away to avoid it.In life, St. Therese made it her daily practice to not only not react in anger or frustration in the face of hardship and annoyances, but to also do nothing to avoid them or ward them off, accepting each such moment as a small share in the Cross of Christ. I share her love of the Cross, and even her wish to bear it in sacrifice, but like so many of you I sure do struggle with her daily example of living it in the face of annoyance.Last Sunday afternoon, for example, I had just finished typing the last page of Part One of this two-part post. I sat down with a pencil to proofread it when my young friend, Ralph Carey came rushing into my cell. I mentioned Ralph months ago in "Les Miserables: The Bishop and the Redemption of Jean Valjean" which has a few parallels with his life. Always like an accident going someplace to happen, Ralph plopped down a book in front of me to ask for the meaning of a word, and knocked over my just-poured cup of coffee ruining beyond salvation the post I had just spent hours typing. It's amazing how the volume of a cup of coffee expands exponentially when outside the cup. It was everywhere."Oops! My bad!" he said, "But at least none got on my book!" What I was thinking was not exactly the practice of non-resistance to hardship lived daily by St. Therese. What I was thinking cannot be printed on a respectable Catholic blog.To be fair to myself, I did not explode at Ralph. He would have been very hurt had I done so, and so for the sake of that I contained my frustration. Instead of exploding, I let him make me another cup of coffee - then asked him to set it down at least ten feet away from me while I set up my typewriter for round two.In his HPR article, Brent Withers went on to suggest that experiences of frustration and hardship should be spontaneously offered for the souls in Purgatory who are forgotten and unnoticed. And not only should the hardship be so offered, says the writer, but also the sin which follows - the impatience and frustration and anger that wells up in response to such events. When I read this, I had an immediate image in my mind that if I offer all the moments of impatience, frustration and anger that prison brings to me, I might cause a veritable stampede out of Purgatory.THE CHALLENGE OF SAINT MAXIMILIANI know many of you have read Pornchai Moontri's guest post on These Stone Walls last year entitled, "The Duty of a Knight: To Dream the Impossible Dream." In powerful words, Pornchai wrote of his own spiritual journey and of how St. Maximilian insinuated himself into Pornchai's life almost perfectly parallel to the ways he came to me.I remember the day Pornchai and I landed in the same cell. We had already been friends for a year or so when both our cellmates were suddenly moved to another place. Prisoners here have no say where they will live and with whom. The next day, I was moved into the cell with Pornchai. He had been away working in the wood carving shop as I moved in. Later that day when he came into the cell, he saw the image of St. Maximilian above the shaving mirror near the cell door as described in Part One of this post. Pornchai stared at it closely, and to my surprise he asked, "Is this you?""Far from it," I said. I then told Pornchai the story of St. Maximilian, of what he did at Auschwitz, of his canonization by Pope John Paul II in 1982 as a Martyr of Charity just months after I was ordained, and of how and why his image came to be above my mirror all of which I described last week.Pornchai took this all in with an intensity and focus I had never seen in him before. In the months to follow, other prisoners stopped at our cell, and when they asked about the man above the mirror, Pornchai told them the story of St. Maximilian. I saw taking place within him the very transformation that Maximilian brought about in me - an awareness that the events in my life may not be all about me, that some higher purpose is at work, and that I have a choice. I can choose the triumph of injustice. I can be its victim, bitter and resentful, while I passively implore my Patron Saint's intercession to be delivered from it all. Or I can choose to emulate him, to be like the prisoner-priest above my mirror.I first became aware of the spiritual dialogue between St. Maximilian and Pornchai, however, when the latter started talking about designing a ship that he wanted to name for his new Patron Saint. I described Pornchai's great skill at woodcraft in "Come Sail Away! Pornchai Moontri and the Art of Model Shipbuilding." Over the succeeding weeks, Pornchai showed me drawings of his design for the St. Maximilian with its planned black hull. Then half way through building it, Pornchai told me early one morning that he decided to add white and red to the hull of the St. Maximilian. I asked him why, and he said, "I don't know; it just came to me." He had no way to know the significance of these colors for St. Maximilian who once had a vision in which a beautiful woman came to him bearing two crowns for him to choose from. One was white and the other red. They symbolized the crowns of sanctity and martyrdom, both to which Maximilian would one day be called. While this story was unknown to Pornchai, both colors came to adorn the beautiful ship's hull.While this saint was preserving my priesthood from prison, he was also calling Pornchai's soul back from the brink to alter the course of his life. Over the ensuing months, Pornchai on his own made a decision to become Catholic, and took the name "Maximilian" as his Christian name. We both then decided to consecrate our lives as prisoners to Saint Maximilian's two movements, the Militia of the Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross. Readers are invited to join us in this Consecration of suffering by beginning the nine days of preparation before any Marian feast at www.Consecration.com.Our friendship with St. Maximilian has had a vast influence on our lives as I described in another TSW post entitled "Of Saints and Souls and Earthly Woes: Viva Cristo Rey!” If you have a Patron Saint and want to understand how that relationship goes beyond mere advocacy to emulation, please read that post anew. It has an image of St. Maximilian with his two crowns of white and red ensnarled in the razor wire of Auschwitz, an image that is now a daily reminder on my cell wall.Prisoners still stop and look and ask, "Is this you?" and I still answer truthfully, "Far from it!"

Then half way through building it, Pornchai told me early one morning that he decided to add white and red to the hull of the St. Maximilian. I asked him why, and he said, "I don't know; it just came to me." He had no way to know the significance of these colors for St. Maximilian who once had a vision in which a beautiful woman came to him bearing two crowns for him to choose from. One was white and the other red. They symbolized the crowns of sanctity and martyrdom, both to which Maximilian would one day be called. While this story was unknown to Pornchai, both colors came to adorn the beautiful ship's hull.While this saint was preserving my priesthood from prison, he was also calling Pornchai's soul back from the brink to alter the course of his life. Over the ensuing months, Pornchai on his own made a decision to become Catholic, and took the name "Maximilian" as his Christian name. We both then decided to consecrate our lives as prisoners to Saint Maximilian's two movements, the Militia of the Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross. Readers are invited to join us in this Consecration of suffering by beginning the nine days of preparation before any Marian feast at www.Consecration.com.Our friendship with St. Maximilian has had a vast influence on our lives as I described in another TSW post entitled "Of Saints and Souls and Earthly Woes: Viva Cristo Rey!” If you have a Patron Saint and want to understand how that relationship goes beyond mere advocacy to emulation, please read that post anew. It has an image of St. Maximilian with his two crowns of white and red ensnarled in the razor wire of Auschwitz, an image that is now a daily reminder on my cell wall.Prisoners still stop and look and ask, "Is this you?" and I still answer truthfully, "Far from it!"