“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Apostle Falls: Simon Peter Denies Christ

The fall of Simon Peter was a scandal of Biblical proportions. His three-time denial of Jesus is recounted in every Gospel, but all is not as it first seems to be.

The fall of Simon Peter was a scandal of Biblical proportions. His three-time denial of Jesus is recounted in every Gospel, but all is not as it first seems to be.

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: At Beyond These Stone Walls, I try to present many important matters of faith, but I also try not to overlook the most important of all: Salvation. In 2023 we began what I hope will be an annual Holy Week and Easter Season tradition by composing past Holy Week posts into a personal Easter retreat. The posts follow a Scriptural Way of the Cross. You are invited to ponder, pray and share them in our season of Highest Hope. They are linked again at the end of today’s post.

+ + +

Holy Week, March 27, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

I had been 17 years old for only one month when I graduated from high school in May, 1970. Unlike most of my peers, I was too young to go to war in Southeast Asia. Some of my friends who went never came back. On my 17th birthday in April,1970, President Richard Nixon ordered U.S. troops into Cambodia while the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam began. Across this nation, college campuses erupted into violence and walkouts. At Kent State in Ohio, four students were killed by national guardsmen sent to prevent rioting. In response to the protests, Congress passed an amendment to block U.S. troop incursions beyond South Vietnam.

The measure did not forbid bombing, however, so U.S. air strikes continued and increased in Cambodia until 1973. The combined effects of the incursion and bombings completely disrupted Cambodian life, driving millions of peasants from their ancestral lands into civil war. The Khmer Rouge was formed and then became one of the deadliest regimes of the 20th century. Meanwhile, the United States was yet again in a state of rage. Satan loves rage.

This was the setting of my life at seventeen. It seemed that evil was all around me then, but not yet in me. As 1970 gave way to 1971 and I turned eighteen, The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty was published by Harper and Row. I do not today recall how or why I came to have a copy of it so hot off the presses, but I read The Exorcist within weeks of its publication. I cannot say that I devoured it. At one point, I feared it might devour me.

The book left a vivid imprint on me, so much so that halfway through it I had to set it aside for a month. In its pages I came face to face with the personification of evil, accepting that it was a catalyst behind so much of this world’s agony. But I also had no delusion that I was any match for it. William Peter Blatty’s disturbing story of demonic possession seemed to be an allegory for what was happening in the world in which I lived.

Two years later, in 1973, the film version of The Exorcist was produced to scare the hell out of (or into) the rest of the nation that had not yet read the book. Because I did read the book, I was somewhat steeled against the traumatic impact that so many felt from the film. Its influence was evident in its awards. The Exorcist won the Academy Award for Best Writing and Screenplay for William Peter Blatty, and Golden Globe Awards for Best Motion Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, and Best Actor.

An Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress went to Linda Blair for her unforgettable portrayal of Regan, the possessed and tormented young target of an unnamed demon. The film’s producers hired a priest, Father William O’Malley, to portray “Father Dyer,” one of the priest-characters in the book and film. That lent itself to an aura of realism present throughout the book.

Ultimately, The Exorcist also set in motion my resolve to find something meaningful to embrace in life. I began to explore more deeply the Catholic faith that my family previously gave only a Christmas and Easter nod to. I felt called to a journey of faith just as most of my peers were abandoning theirs, but it did not last long. At the same time, my family was disintegrating and I was powerless to stem that tide and the void it left behind.

I was haunted by a sense that even as I embraced the Sacraments of Salvation, evil and its relentless pursuit of souls was never far behind in this or any age. Both seemed in pursuit of me. I was living in a verse reminiscent of Francis Thompson’s epic poem, “The Hound of Heaven” which begins:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days ;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years ;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the midst of tears

I hid from Him.

Not even Satan can hide from God. I wrote the previously untold story of my path to priesthood on the 41st anniversary of my ordination. It was “Priesthood Has Never Been Going My Way.”

While pursuing a degree in psychology in the later l970’s, I had an interest in the work of psychoanalyst Erik Erikson and his stages of human development. Erikson predicted that in the latter years of our lives — the years I am in now — we enter a crisis of “generativity versus despair.” Many of us begin recalling and recalibrating the past, especially at “inflection points,” the points at which we changed. At this writing, I am 70 years old and counting. I realized only in later years that The Exorcist was an unexpected inflection point in my life, a point at which I turned from one path onto another.

The Betrayer Judas Iscariot

Even at age seventeen, the Catholic experience of Holy Week became a most important time for me. I began then to see clearly that the events of Holy Week were a nexus between the promises of Heaven and the pursuits of hell. The sneakiest thing Satan has ever done in the modern world was to get so many in this world to cease believing in him, and then to marginalize God. Many in the current generation calling itself “woke” now believe that Satan, if even real at all, has just been misunderstood.

The nightmarish story of The Exorcist was like a battleground. I was deeply impacted by a scene near the end of the book and film when the Exorcist, Father Damien Karras, tricked the demon into leaving young Regan and entering himself. He then leapt through a high window to his death on the Georgetown streets of Washington, DC down below. The scene set off a national debate. Had Father Karras despaired and committed suicide? Or had he heroically saved the devil’s victim by sacrificing himself?

Just as I was recently pondering this idea, I was struck by the photo atop this section of my post. It is my friend, Pornchai Moontri standing against a map of Southeast Asia which, I just now realized, is also where this post began. I had seen the photo previously in his January 2024 post, “A New Year of Hope Begins in Thailand,” but I failed to look more closely at it then.

Look closely at the T-shirt Pornchai is wearing in the photo. It quotes another inflection point in both his life and mine. His T-shirt bears a quote from St. Maximilian Kolbe who became a Patron Saint for us and who deeply impacted our lives. Maximilian also sacrificed his life to save another. His simple but profound quote on Pornchai’s T-shirt is, “Without Sacrifice,There Is No Love.”

That is how Father Damien Karras defeated the devil. Pornchai today says it is also how he was released from the prison of his past. And it is how Jesus conquered death and opened for us a path to Heaven. Sacrifice is the “Narrow Gate” He spoke of, the passage to our true home.

Earlier this Lent, I wrote “A Devil in the Desert for the Last Temptation of Christ.” It was about how Satan first set his demonic sights in pursuit of Jesus Himself. What utter arrogance! At the end of that account, having given it his all, the devil in the desert “departed from him until an opportune time.” (Luke 4:13)

By his very nature, the betrayer Judas Iscariot provided this opportune time. The Gospel gives many hints about his greed and ambition, traits that leave many open to the subtle infiltration of evil. Satan plays the long game, not only in human history, but also in a person’s life and soul. In the allegorical book, The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis laid out the long, subtle trail upon which we humans risk the slippery slope toward evil:

“It does not matter how small sins are provided that their cumulative effect is to edge a person away from the Light and out into the Nothing ... . Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one - the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”

— The Screwtape Letters, Letter #12, p. 60-61

Judas Iscariot gave Satan a lot to work with. He served as a treasurer for the Apostles but he embezzled from the treasury. The Gospel of John described him as “a devil” (6:70-71), “a thief” (12:6), “a son of destruction” (17:12).

The Gospel makes clear that Jesus was betrayed because “Satan entered into Judas called Iscariot” (Luke 22:3). At the Passover meal (John 13:26-30), Jesus gave a morsel of bread to Judas. When Judas consumed it, “Satan entered into him.” That would not have been possible had Judas truly believed in the Christ. The Gospel of John then ends this passage with a chilling account of the state of Judas’ life and soul: “He immediately went out, and it was night.” (John 13:30).

In the scene laid out in the Gospel of John above, Satan finds his opportune time when Judas let him in. I wrote of a deeper meaning in this account in one of our most-read posts of Holy Week, “Satan at the Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light.”

The Turning of Simon Peter

The Eucharist had just been instituted and shared by Jesus among his Apostles. All the Gospels capture these moments. All are inspired, but Luke is my personally most inspiring source. The Evangelist cites at the very end of the meal its true purpose: “This chalice which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood” (Luke 23:20). Jesus adds that “The Son of Man goes as it has been determined, but woe to that man by whom he is betrayed.”

The others at the Table of the Lord are alarmed by all this talk of Jesus being betrayed. They launch immediately into a dispute about who among them would do such a thing, who among them would never do such a thing, and finally who among them is the greatest (Luke 22:26). Simon Peter leads that last charge, but first we need to look at what has come before. How and why did Simon come to be called Peter? The answer opens some fascinating doors leading to events to come.

On a hillside in Bethsaida, a fishing village on the north side of the Sea of Galilee, a vast crowd gathered to hear Jesus. They numbered about 5,000 men. This was Simon’s hometown so he likely knew many of them. After a time, the disciples asked Jesus to send the crowd away to find food. Jesus instructed the disciples to give them something to eat. They protested that they had only seven loaves of bread and a few meager fish.

In a presage of the Eucharistic Feast, Jesus blessed and broke the bread, and with the few fish, a symbol of Christ Himself, the disciples fed the entire multitude on the hillside (Luke 9:10-17). Immediately following this, Jesus asked his disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” Simon replied, “You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God.” Simon is thus given a new and transformative name and mission:

“You are Peter (in Greek, Petra and in Aramaic, Cephas — both meaning “rock”) and on this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.”

This is more than a figurative gesture. In the Hebrew Scriptures, Hades is the abode of the dead, the place where souls descend through its gates to an eternal Godless realm of the dead (Psalm 9:13, 17 and Isaiah 38:10) where they are held until the Last Judgment. It is the precursor to our traditional concept of hell being under the Earth, the place of the habitation of evil forces that bring about death.

In Hebrew tradition, the Foundation Stone of the Temple at Jerusalem, called in Hebrew “eben shetiyyah,” was a massive stone believed since ancient times to seal and cap off a long shaft leading to the netherworld (Revelation 9:1-2 and 20:1-3). It is this particular stone that the Evangelist seems to refer to as the rock upon which Jesus will build His Church. The Jerusalem Temple, resting securely on this impenetrable rock, was thus conceived to be the very center of the Cosmos and the junction between Heaven and Hell.

Jesus assures Peter, from the Biblical Greek meaning “rock,” that Peter and his successors will have the figurative keys to these gates and the power to hold error and evil at bay. By being equated with the very Foundation Stone itself, Peter is given the unique status of a prime minister, a position to be held for as long as the Kingdom stands.

Later in Luke’s Gospel, Simon Peter insists that he is “ready to go to prison and even death” with Jesus. Jesus corrects him saying, “Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail; and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren.” (Luke 22 : 31-32)

We all know, now, that Peter’s faith did fail. It gave way to fear and led him to three times deny being with, or even knowing, Jesus. But there is a lot more packed within that brief statement of Jesus above. The word “you” appears three times in the short verse. Like the rest of Luke’s Gospel, it is written in Biblical Greek. The word used for the first two occasions of “you” is plural. It refers to all of the Apostles, except Judas who had already gone out into the night.

The third use of the word “you” in that passage is singular, however, referring only to Peter himself. Jesus knew he would fall because his human nature had already fallen. But, “When you have turned again, strengthen your brethren.” Peter’s three-time denial of Jesus pales next to the betrayal of Judas from which there is no return. The story of Peter’s denial is remedied, and he “turns again” in the post Resurrection appearance at the Sea of Galilee (John 21:15-19).

Jesus brings restorative justice to Peter’s three-time denial by asking him three times to “feed my lambs,” “tend my sheep,” “feed my sheep.” Then Jesus tells Peter what to expect of his unique apostolate:

“Truly, truly I say to you, when you were young, you fastened your own belt and walked where you would; but when you are old, you will stretch out your hands, and another will fasten your belt for you and carry you where you do not wish to go”

— John 21:18

This was to foretell the assaults from beyond the Gates of Hell to which the Church will be subjected. And then, in John 21:19, He spoke His last words to Peter which, in Matthew 4:19, were also His first words to Peter. Through them, He speaks now also to us in this Holy Week of trials, assailed from all sides:

“Follow me.”

+ + +

“Stay sober and alert for your opponent the devil prowls about the world like a roaring lion seeking someone to devour. Resist him steadfast in the faith knowing that your brethren throughout the world are undergoing the same trials.”

— First Letter of Peter 5:8-9

+ + +

Photo by Nicolas Grevet (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED)

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: You are invited to make our Holy Week posts a part of your Holy Week and Easter Season observance. I cannot claim that they are bound in Earth or Heaven, but we will retain them at our “Special Report” feature until the conclusion of the Easter Season at Pentecost:

The Passion of the Christ in an Age of Outrage (2020)

Overshadowing Holy Week with forced pandemic restrictions and political outrage recalls the Bar Kochba revolt of AD 132 against the Roman occupation of Jerusalem.

Satan at the Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light (2020)

The central figures present before the Sacrament for the Life of the World are Jesus on the eve of sacrifice and Satan on the eve of battle to restore the darkness.

Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane (2019)

The Agony in the Garden, the First Sorrowful Mystery, is a painful scene in the Passion of the Christ, but in each of the Synoptic Gospels the Apostles slept through it.

The Apostle Falls: Simon Peter Denies Christ (2024)

The fall of Simon Peter was a scandal of biblical proportions. His three-time denial of Jesus is recounted in every Gospel, but all is not as it first seems to be.

Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands (2014)

‘Ecce Homo,’ an 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri, depicts a moment woven into Salvation History and into our very souls. ‘Shall I crucify your king?’

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’ (2017)

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

Simon of Cyrene Compelled to Carry the Cross (2023)

Simon of Cyrene was just a man on his way to Jerusalem but the scourging of Jesus was so severe that Roman soldiers feared he may not live to carry his cross alone.

Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found (2012)

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Salvation.

To the Spirits in Prison: When Jesus Descended into Hell (2022)

The Apostles Creed is the oldest statement of Catholic belief and apostolic witness. Its Fifth Article, what happened to Jesus between the Cross and the Resurrection, is a mystery to be unveiled.

Mary Magdalene: Faith, Courage, and an Empty Tomb (2015)

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous, and noble woman, an Apostle to the Apostles.

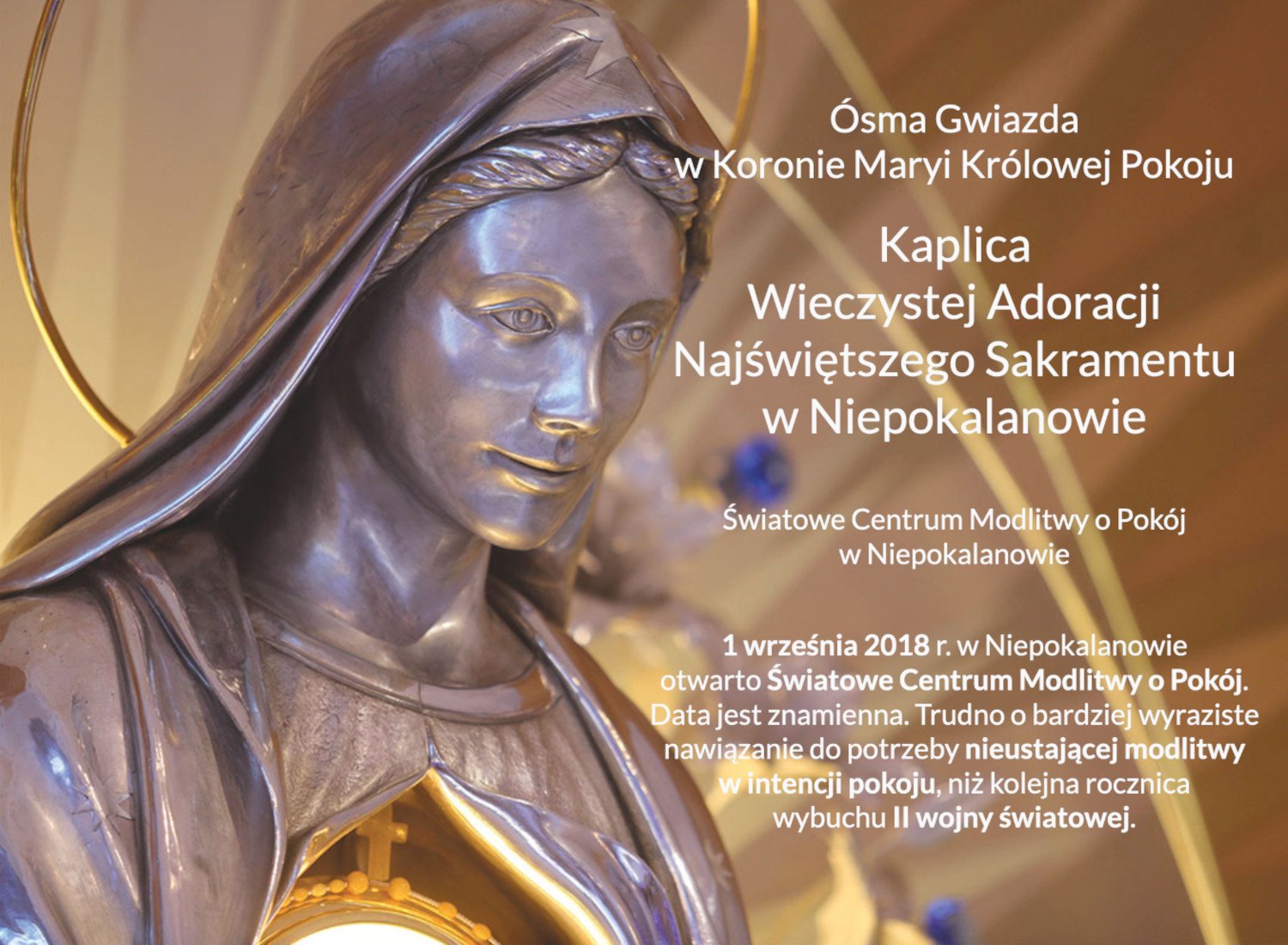

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Cry Freedom! Saint Paul and a Prisoner of the Apocalypse

Two prior posts from Beyond These Stone Wa11s revisit the idea1 of freedom, what it means to find it, what it costs to keep it, what it takes to give it to another.

Two prior posts from Beyond These Stone Walls revisit the ideal of freedom, what it means to find it, what it costs to keep it, what it takes to give it to another.

Some readers who are aware of my day to day life as a guest of the state have heard that I was held in a high security quarantine dormitory setting for the entire month of May and part of June in 2021. I did write briefly of this just before it happened, but it seems that what I wrote was too cryptic. I just received a letter from a reader who wanted to launch a petition over my continued heightened confinement. Please don’t show up here with picket signs. I am now liberated from my dungeon.

I was not technically in quarantine. Due to a planned construction project where I was living, I and 23 others were moved to an unused dormitory space that had been previously set up as a Covid-19 triage and quarantine area. It commenced on May 1 and was supposed to last for just ten days at which time, it was promised, we would all move back to our housing assignments.

The construction ran into obstacles, however, and the predicted ten days ultimately turned into forty. During that time, I was pretty much locked into a crowded, noisy room with 23 other disgruntled prisoners. I had no access to my typewriter while there so writing was extremely difficult. Somehow, I still managed to write three posts, but with great difficulty. One of them was for my 39th anniversary of priesthood entitled, “It Is the Duty of a Priest to Never Lose Sight of Heaven.”

I wrote that post “by fits and starts,” a term meaning “haphazardly” that has gone out of style in writing. I wrote that post only in my mind. I was still able to work, as needed but with greatly reduced hours, in the prison law library where I am the sole legal clerk. There is an old manual typewriter there, so I managed to type that post over two hours one afternoon. I mailed it just at the final deadline to have it posted on time. I hope its troubled creation was not so evident.

I could not bring myself to complain about the forty-day confinement. I was constantly aware that our friend, Pornchai Moontri, spent five full months in ICE detention awaiting deportation in a room of the same size, but housing 60 to 70 detainees at any one time. That story should become another BTSW classic post on freedom. The gripping story is told in “ICE Finally Cracks: Pornchai Moontri Arrives in Thailand.”

More importantly, it was also impossible for me to offer Mass during my stay in what I can only describe as “a FEMA shelter without the disaster.” I had hoped to offer Mass on June 6, the Solemnity of Corpus Christi this year and the anniversary of my First Mass on the day after my priesthood ordination on June 5, 1982. But it was not meant to be. After forty days, we were all finally liberated and returned to the place in which I have lived since July of 2017.

It is difficult for me to believe that it was four years ago this month that Pornchai and I were finally moved to that better housing. For the previous 23 years — 12 for Pornchai — we were prisoners in a building housing 504 prisoners but built for half that number. There was little to no access to the outside. It contained all the trouble and chaos that such constant confinement brings.

But we are now free from that. Even in a state of unjust imprisonment, I can thank God for the freedoms I have. I am free to write to the world beyond these stone walls which means more to me than you may know.

As I pondered Independence Day in America this year, I realized that it falls on the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time. This time is anything but ordinary for me and Pornchai. When I looked at the Mass readings for that day, I noted that I wrote of those same readings for Independence Day six years ago. So I want to invite you to visit that post anew. It is the story of Saint Paul and his plea to be free of his famous but cryptic “thorn in the flesh.”

The second post I want to present anew is a memorable one you also may have previously read. It is brief, but you should not miss it.

+ + +

Independence Day: St Paul and His Thorn in the Flesh

A Mass Reading from Second Corinthians on the 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time conveys Saint Paul’s thorny lesson about freedom and power. Our world has it all wrong.

It is not by design, but the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time falls on Independence Day in the United States in 2021. The Mass readings assigned to that day (Lectionary 101 – Year B) have an important lesson about the nature of freedom and the source of true power. The lesson’s focal point, as in every Mass, is the Gospel (Mark 6:1-6). Jesus concludes that the people in his own “native place” would not hear Him, but “only took offense at Him.” I certainly know the feeling.

These were his own people. The Gospel mentions that they knew Joseph. They knew Mary. They knew some of the Apostles, but Jesus “was amazed by their lack of faith.” He concluded famously that “A prophet is not without honor except in his native place, and among his own kin, and in his own house” (Mark 6:4). It is having confronted that reality that the Mission of Christ Universal begins to unfold.

As I read this Gospel passage, I thought of a letter sent to me two years ago by Cardinal Raymond Burke. In it, he expressed his concern for my plight and asked for my prayers for him and for the Church. His words suggesting that I offer some of what I endure for a greater good — “pro bono Ecclesiae,” a phrase taught to us recently in Father Stuart MacDonald’s provocative post, “Last Rights: Canon Law in a Mirror of Justice Cracked.”

Cardinal Burke’s request that I suffer for something greater than suffering was an honor without measure. I wrote of this in a Christmas post last year. Here is an excerpt from my post, “Silent Night and the Dawn of Redeeming Grace.”

This letter is among the best Christmas gifts I have received out here among the Church’s debris, and it came as a source of grace, a sort of awakening. What follows may be the most important sentence in this post: There is no greater service to those who suffer than to give meaning to what they suffer.

A few months after my receipt of Cardinal Burke’s letter, a bishop came to this prison to offer Mass on Divine Mercy Sunday. Our friend, Pornchai Moontri and I were among the fifty Catholic prisoners gathered in the prison chapel for Mass. You know Divine Mercy Sunday is a special day for us.

After the Mass, as we filed out, the Bishop grasped my hand and said something very strange to me. He had obviously been reading These Stone Walls. As he took my hand, he bent forward a bit and said quietly but forcefully, “You are a prophet! YOU are a prophet.” There was no further exchange.

As we descended down the long flights of stairs outside, my friend, Pornchai said, “Wow! That was weird. What do you think it means?” I responded sarcastically, “If the Church is consistent, it means my head is about to be lopped off!”

Our prophets do not fare very well. In Scripture, some were thrown into prison. The Prophet Jeremiah was stoned to death. According to legend, the Prophet Isaiah was sawed in half. The Prophet Jonah was thrown overboard. John the Baptist was beheaded. Saint Paul was shipwrecked, beaten, imprisoned, and finally martyred.

As the great Saint Teresa of Avila once said to God in prayer, “Lord, if this is how you treat your friends, it is no wonder that you have so few!”

The Gospel is, of course, the centerpiece of the Liturgy of the Word, but on the 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time it is the Second Reading that really leaps off the page in my quest for my own Independence Day. It is Saint Paul’s famous account from the Second Letter to the Corinthians (12:7-10) about his thorn in the flesh:

“… A thorn in the flesh was given to me, an angel of Satan, to beat me, to keep me from being too elated. Three times I begged the Lord about this, that it might leave me, but he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ ”

Scripture scholars — both real and imagined — have pondered for centuries to decipher what this cryptic thorn in the flesh could mean. Some have interpreted it to mean a physical ailment or disability of some sort that rendered Paul weak and challenged. His phrase, “my power is made perfect in weakness” lends itself to that theory when you consider the vast influence he has had on the growth of Christianity.

THE AGENT OF SATAN

Others have suggested that his thorn in the flesh was the manifestation of some mental illness which, in Saint Paul’s time, was often described in Jewish tradition as a manifestation of Satan or some other demonic attack. His words, “to beat me, to keep me from being too elated” suggest a sense of personal diminishment that could support a theory about some mental condition such as bouts of chronic depression or anxiety.

In more modern times, some have suggested with a straight face that the thorn in the flesh could be an allusion to some morally compromising sexual proclivity over which Paul experienced little self-control. I believe that all three of these theories are incorrect, and the third one is far more descriptive of the preoccupations of our own time than Saint Paul’s.

I have formed my own conclusions about Paul’s mysterious “thorn in the flesh,” and they come from a more panoramic understanding not just of what he wrote, but also of who he was — and is. I believe his “thorn in the flesh” is a person, someone who stood in hostile opposition to Paul and his missionary activities.

Saint Paul, formerly Saul, was a Jew born in the town of Tarsus in the Roman Province of Celicia. In his Letter to the Romans (11:1) he revealed that he was from the Tribe of Benjamin. He was also a Roman citizen which gave him certain rights and privileges. In Acts of the Apostles (22:25-29) Paul was about to be scourged by a Roman tribune. When it was learned that he was a Roman citizen by birth, the punishment was halted.

Paul was also a zealous member of the Pharisees (Acts 26:5). This meant that in Jewish circles, he was highly educated in the law and Jewish Scripture and traditions. His writing has to be seen in this context, and the phrases he used have to be weighed against the Hebrew Scriptures with which he was thoroughly familiar.

In those Scriptures, the word, “thorns” is often symbolically used to refer to enemies. The context for its use by Paul in the excerpt from Second Corinthians cited above was not that the “thorn in my flesh” was placed there by Satan, but rather is described as “an agent of Satan.” This presents an impression that this thorn is a person in hostile opposition to Paul.

As a Pharisee, Paul would have been thoroughly familiar with the Torah, the Books of Moses held to be especially sacred. The Book of Numbers, which is a re-telling of the Exodus story and the arrival of the Israelites in the Promised Land, contains an allusion with which Paul would have been very familiar:

“But if you do not drive out the inhabitants of the land from before you, then those whom you let remain shall be as barbs in your eyes and thorns in your side.”

Saint Paul’s description of this “thorn” as a “servant” or “angel” (messenger) of Satan suggests that Paul was faced with a growing personal hostility and oppression from someone within his own community. By “his own community,” I mean his Jewish community and not the community of believers in “The Way.” It was more likely someone in the Jewish community who oppressed Paul because his allusion to the thorn as depicting an enemy is a purely Old Testament Jewish symbolism.

So the only remaining mystery is not “what” the thorn in his flesh was but rather who. It was during Paul’s Second Missionary Journey commencing in 50 A.D. that he established the Church in Corinth, a city in Greece on the Isthmus of Corinth. Paul remained there for over a year, but before departing he was viciously attacked by an unnamed enemy (2 Corinthians 11:13).

The unnamed enemy may well be the thorn in Saint Paul’s flesh. Paul was a Pharisee who had previously persecuted Christians, capturing them and handing them over for stoning. He was deeply committed to the Pharisaic tradition of maintaining legal and ritual purity for the Jews. Now Paul was promoting this new faith, and not only promoting it, but actively welcoming gentiles to its ranks.

It was during his Third Missionary Journey to Macedonia that he wrote the Second Letter to the Corinthians in 53 A.D. He wrote it from Philippi in Macedonia. Then, proceeding to Corinth, he wrote his Letter to the Romans. At the time he wrote both Second Corinthians and Romans, he began to speak of his impending imprisonment and martyrdom.

Saint Paul’s allusion that “Three times I begged the Lord” about the thorn in his flesh, i.e., the hostility he encountered — likely refers to a leader in the Jewish community. Using the past tense, “begged,” infers that he has stopped begging, and has accepted the answer that came to him:

“My grace is sufficient for you, for my power [the power of God] is made perfect in [your] weakness.”

The power Paul encounters is manifested in his acceptance of weakness, meaning his acceptance that it is not his own gifts and talents that are driving the bus on this mission:

“I will rather boast: most gladly of my weaknesses, in order that the power of Christ may dwell with me. Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and constraints for the sake of Christ; for when I am weak, then I am strong.”

Independence Day thus dawned for the Apostle Paul.

+ + +

Left Behind: In Prison for the Apocalypse

This medium security prison has a library where I have been a prisoner-clerk for the last ten years. Its shelves are stocked with 21,000 volumes. With an average of 1,000 visits, and some 3,000 books checked out each month, the library is a literary hub intersecting virtually every facet of prison life. But there is a lot more going on than books flying off the shelves.

There are few proud moments in prison, but one of mine came in the form of a second-hand message from my friend Skooter, now free. Two months after Skooter ascended through the corrections system to finally hit the streets, another friend of his was sent back to prison for a parole violation.

That friend came to the library one day, and standing at my desk, said, “You’re the guy who broke Skooter out of prison!” The man explained that he lived near Skooter in a seedy urban rooming house while both were unemployed and barely surviving in their first few months on parole. He said that Skooter had been unable to land a job, working in temp jobs for minimum wage and at times faced with a choice between food and rent.

It is an all-too-familiar account for young men struggling to emerge not just from a prison, but from a past. Skooter came very close to giving up, the friend said, but often spoke of his “wanting very much not to disappoint you” by coming back to prison. “So he stayed the course,” said the friend, “and now he’s gotten his life together.”

I first met Skooter several years earlier, one of the scores of aimless, rootless, fatherless, uneducated young men for whom prison can become a warehouse, a place in which thousands of “Skooters” store their aimless, hopeless futures. One day as we slowly ascended the multiple flights of stairs to be checked in at the Education Floor where the prison library is located, Skooter told me with a sense of shame that, at age 24, he had never learned to read or write.

Having resisted all the concerted efforts to recruit him into any number of prison gangs that would only foster his ignorance and exploit it, Skooter became a regular fixture in the prison library. For an hour a day there, I and other prisoners worked with Skooter to teach him to read and write.

My friend, Pornchai Moontri tutored him in math, Skooter’s most feared academic nemesis. We made sure he didn’t starve, and in return, he struggled relentlessly toward earning his high school diploma in prison, a steep ascent in a place that by its very nature fosters humiliation and shuns personal empowerment.

One day, shortly before his high school graduation in May 2011, Skooter came charging into the library looking defeated. He plopped before me the previous day’s copy of USA Today, opened to a full-page ad by some self-proclaimed Prophet-of-the-End-Time announcing that the world is to end on May 21, 2011, a week before Graduation Day.

“It’s just my luck’” lamented Skooter. “I do all this work and the world’s gonna end just before I graduate.” “It’s not true,” I said calmly. “It MUST be true,” Skooter shot back. “They wouldn’t put it in the paper if it wasn’t true!” Like many prisoners, and far too many others, Skooter believed that all truth was carefully vetted before ending up in newsprint.

Apocalyptic predictions sometimes play out strangely in prison. I told Skooter that back in 1999, a prisoner I knew became convinced of dire consequences from a looming technological Armageddon called “Y2K.” ‘That prisoner deduced somehow that prison officials would release toxic gas at the turn of the millennium so he spent the night of December 31 sewing his lips and eyes shut. Skooter wanted to know how the guy managed to sew that second eyelid, a small tribute to his deductive reasoning.

I pointed out to Skooter in the USA Today ad’s smaller print that this newest End-Time prediction was actually a revision of the author’s previous one set in 1994. I strongly urged Skooter not to put off studying for final exams because of this. Skooter stayed the course.

Since then, a subsequent prison policy barred all prisoners from teaching and tutoring other prisoners, a decision that effectively eliminated all of the positive influence, and none of the negative influence, that takes place in prison, driving the former underground.

Still, that graduation was Skooter’s finest moment, and one of my own as well. It was a direct result of a prison library subculture that grants every prisoner a few hours a week out of prison into an arena of books, a world of ideas, a release of huddled neurons yearning to be free.

A week after graduation, Skooter showed up in the library with a copy of The Wall Street Journal opened to an article by science writer, Matt Ridley. The article explored evidence that the Earth’s magnetic core shifts polarity every few hundred thousand years, and pointed out with dismal foreboding that it is 780,000 years overdue. Mr. Ridley stressed that no one knows its potential impact on our global technological infrastructure.

“It’s just my luck!” lamented Skooter as he plopped the article on my desk. “Just when I was thinkin’ about college!”

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please visit our “Special Events” page.

+ + +

Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed

Saint Michael the Archangel is often depicted wielding a sword and a set of scales to vanquish Satan. His scales have an ancient and surprising meaning.

Saint Michael the Archangel is often depicted wielding a sword and a set of scales to vanquish Satan. His scales have an ancient and surprising meaning.

I worked for days on a post about Saint Michael the Archangel. I finally finished it this morning, exactly one week before the Feast of the Archangels, then rushed off to work in the prison library. When I returned four hours later to print the post and get it into the mail to Charlene, my friend Joseph stopped by. You might remember Joseph from a few of my posts, notably “Disperse the Gloomy Clouds of Night” in Advent and “Forty Days and Forty Nights” in Lent.

Well, you can predict where this is going. As soon as I returned to my cell, Joseph came in to talk with me. Just as I turned on my typewriter, Joseph reached over and touched it. He wasn’t aware of the problem with static charges from walking across these concrete floors. Joseph’s unintentional spark wiped out four days of work and eight pages of text.

It’s not the first time this has happened. I wrote about it in “Descent into Lent” last year, only then I responded with an explosion of expletives. Not so this time. As much as I wanted to swear, thump my chest, and make Joseph feel just awful, I couldn’t. Not after all my research on the meaning of the scales of Saint Michael the Archangel. They very much impact the way I look at Joseph in this moment. Of course, for the 30 seconds or so after it happened, it’s just as well that he wasn’t standing within reach!

This world of concrete and steel in which we prisoners live is very plain, but far from simple. It’s a world almost entirely devoid of what Saint Michael the Archangel brings to the equation between God and us. It’s also a world devoid of evidence of self-expression. Prisoners eat the same food, wear the same uniforms, and live in cells that all look alike.

Off the Wall, And On

In these cells, the concrete walls and ceilings are white — or were at one time — the concrete floors are gray, and the concrete counter running halfway along one wall is dark green. On a section of wall for each prisoner is a two-by-four foot green rectangle for posting family photos, a calendar and religious items. The wall contains the sole evidence of self-expression in prison, and you can learn a lot about a person from what’s posted there.

My friend, Pornchai, whose section of wall is next to mine, had just a blank wall two years ago. Today, not a square inch of green shows through his artifacts of hope. There are photos of Joe and Karen Corvino, the foster parents whose patience impacted his life, and Charlene Duline and Pierre Matthews, his new Godparents. There’s also an old photo of the home in Thailand from which he was taken at age 11, photos of some of the ships described in “Come, Sail Away!” now at anchor in new homes. There’s also a rhinoceros — no clue why — and Garfield the Cat. In between are beautiful icons of the Blessed Mother, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Saint Pio, and one of Saint Michael the Archangel that somehow migrated from my wall over to Pornchai’s.

My own wall evolved over time. The only family photos I had are long lost, and I haven’t seen my family in many years. It happens to just about every prisoner after ten years or so. In my first twelve years in prison I was moved sixteen times, and each time I had to quickly take my family photos off the wall. Like many prisoners here for a long, long time, there came a day when I took my memories down to move, then just didn’t put them back up again. A year ago, I had nothing on the wall, then a strange transformation of that small space began to take shape.

When These Stone Walls — the blog, not the concrete ones — began last year, some readers started sending me beautiful icons and holy cards. The prison allows them in mail as long as they’re not laminated in plastic. Some made their way onto my wall, and slowly over the last year it filled with color and meaning again.

It’s a mystery why, but the most frequent image sent to me by TSW readers is that of Saint Michael the Archangel. There are five distinct icons of him on the wall, plus the one that seems to prefer Pornchai’s side. These stone walls — the concrete ones, not the blog — are filled with companions now.

There’s another icon of Saint Michael on my coffee cup — the only other place prisoners always leave their mark — and yet another inside and above the cell door. That one was placed there by my friend, Alberto Ramos, who went to prison at age 14 and turned 30 last week. It appeared a few months ago. Alberto’s religious roots are in Caribbean Santeria. He said Saint Michael above the door protects this cell from evil. He said this world and this prison greatly need Saint Michael.

Who Is Like God?

The references to the Archangel Michael are few and cryptic in the canon of Hebrew and Christian Scripture. In the apocalyptic visions of the Book of Daniel, he is Michael, your Prince, “who stands beside the sons of your people.” In Daniel 12:1 he is the guardian and protector angel of Israel and its people, and the “Great Prince” in Heaven who came to the aid of the Archangel Gabriel in his contest with the Angel of Persia (Daniel 10:13, 21).

His name in Hebrew — Mikha’el — means “Who is like God?” It’s posed as a question that answers itself. No one, of course, is like God. A subsidiary meaning is, “Who bears the image of God,” and in this Michael is the archetype in Heaven of what man himself was created to be: the image and likeness of God. Some other depictions of the Archangel Michael show him with a shield bearing the image of Christ. In this sense, Michael is a personification, as we’ll see below, of the principal attribute of God throughout Scripture.

Outside of Daniel’s apocalyptic vision, the Archangel Michael appears only two more times in the canon of Sacred Scripture. In Revelation 12:7-9 he leads the army of God in a great and final battle against the army of Satan. A very curious mention in the Epistle of Saint Jude (Jude 1:9) describes Saint Michael’s dispute with Satan over the body of Moses.

This is a direct reference to an account in the Apocrypha, and demonstrates the importance and familiarity of some of the apocryphal writings in the Israelite and early Christian communities. Saint Jude writes of the account as though it is quite familiar to his readers. In the Assumption of Moses in the apocryphal Book of Enoch, Michael prevails over Satan, wins the body of Moses, and accompanies him into Heaven.

It is because of this account that Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus in the account of the Transfiguration in Matthew 11. Moses and Elijah are the two figures in the Hebrew Scriptures to hear the voice of God on Mount Sinai, and to be assumed bodily into Heaven — escorted by Saint Michael the Archangel according to the Aggadah, the collection of milennia of rabbinic lore and custom.

Saint Michael as the Divine Measure of Souls

In each of the seven images of Saint Michael the Archangel sent to me by TSW readers, he is depicted brandishing a sword in triumph over Satan subdued at his feet. In five of the icons, he also holds a set of scales above the head of Satan. A lot of people confuse the scales with those of “Lady Justice” the famous American icon. Those scales symbolize the equal application of law and justice in America. It’s a high ideal, but one that too often isn’t met in the American justice system. I cited some examples in “The Eighth Commandment.”

The scales of Saint Michael also depict justice, but of another sort. Presumably that’s why so many readers sent me his image, and I much appreciate it. However, some research uncovered a far deeper symbolic meaning for the Archangel’s scales. The primary purpose of the scales is not to measure justice, but to weigh souls. And there’s a specific factor that registers on Saint Michael’s scales. They depict his role as the measure of mercy, the highest attribute of God for which Saint Michael is the personification. The capacity for mercy is what it most means to be in the image and likeness of God. The primary role of Saint Michael the Archangel is to be the advocate of justice and mercy in perfect balance — for justice without mercy is little more than vengeance.

That’s why God limits vengeance as summary justice. In Genesis chapter 4, Lamech, a descendant of Cain, vows that “if Cain is avenged seven-fold then Lamech is avenged seventy-seven fold.” Jesus later corrects this misconception of justice by instructing Peter to forgive “seventy times seven times.”

Our English word, “Mercy” doesn’t actually capture the full meaning of what is intended in the Hebrew Scriptures as the other side of the justice equation. The word in Hebrew is ”hesed,” and it has multiple tiers of meaning. It was translated into New Testament Greek as “eleos,” and then translated into Latin as “misericordia” from which we derive the English word, “mercy.” Saint Michael’s scales measure ”hesed,” which in its most basic sense means to act with altruism for the good of another without anything of obvious value in return. It’s the exercise of mercy for its own sake, a mercy that is the highest value of Judeo-Christian faith.

Sacred Scripture is filled with examples of hesed as the chief attribute of God and what it means to be in His image. That ”the mercy of God endures forever” is the central and repeated message of the Judeo-Christian Scriptures. The references are too many to name, but as I was writing this post, I spontaneously thought of a few lines from Psalm 85:

“Mercy and faithfulness shall meet. Justice and peace shall kiss. Truth shall spring up from the Earth, and justice shall look down from Heaven.”

The domino effect of hesed-mercy is demonstrated in Psalm 85. Faithfulness and truth will arise out of it, and together all three will comprise justice. In researching this, I found a single, ancient rabbinic reference attributing authorship of Psalm 85 to the only non-human instrument of any Psalm or verse of Scripture: Saint Michael the Archangel, himself. According to that legend, Psalm 85 was given by the Archangel along with the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai.

Saint Thomas Aquinas described Saint Michael as “the breath of the Redeemer’s spirit who will, at the end of the world, combat and destroy the Anti-Christ as he did Lucifer in the beginning.” This is why St. Michael is sometimes depicted bearing a shield with the image of Christ. It is the image of Christ in His passion, imprinted upon the veil of St. Veronica. Veronica is a name that appears nowhere in Scripture, but is simply a name assigned by tradition to the unnamed woman with the veil. The name Veronica comes from the Latin “vera icon” meaning “true image.”

Saint Thomas Aquinas and many Doctors of the Church regarded Saint Michael as the angel of Exodus who, as a pillar of cloud and fire, led Israel out of slavery. Christian tradition gives to Saint Michael four offices: To fight against Satan, to measure and rescue the souls of the just at the hour of death, to attend the dying and accompany the just to judgment, and to be the Champion and Protector of the Church.

His feast day, assigned since 1970 to the three Archangels of Scripture, was originally assigned to Saint Michael alone since the sixth century dedication of a church in Rome in his honor. The feast was originally called Michaelmas meaning, “The Mass of St. Michael.” The great prayer to Saint Michael, however, is relatively new. It was penned on October 13, 1884, by Pope Leo XIII after a terrifying vision of Saint Michael’s battle with Satan:

St. Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle. Be our protection against the wickedness and snares of the devil. May God rebuke him, we humbly pray, and do thou, 0 Prince of the heavenly Host, by the power of God, cast into Hell Satan and all the evil spirits who prowl about the world seeking the ruin of souls. Amen.

It’s an important prayer for the Church, especially now. I know the enemies of the Church lurk here, too. There are some who come here not for understanding, or the truth, but for ammunition. For them the very concept of mercy, forgiveness, and inner healing is anathema to their true cause. I once scoffed at the notion that evil surrounds us, but I have seen it. I think every person falsely accused has seen it.

Donald Spinner, mentioned in “Loose Ends and Dangling Participles,” gave Pornchai a prayer that was published by the prison ministry of the Paulist National Catholic Evangelization Association. Pornchai asked me to mention it in this post. It’s a prayer that perfectly captures the meaning of Saint Michael the Archangel’s Scales of Hesed:

“Prayer for Justice and Mercy

Jesus, united with the Father and the Holy Spirit, give us your compassion for those in prison. Mend in mercy the broken in mind and memory. Soften the hard of heart, the captives of anger. Free the innocent; parole the trustworthy. Awaken the repentance that restores hope. May prisoners’ families persevere in their love. Jesus, heal the victims of crime; they live with the scars. Lift to eternal peace those who die. Grant victims and their families the forgiveness that heals. Give wisdom to lawmakers and those who judge. Instill prudence and patience in those who guard. Make those in prison ministry bearers of your light, for ALL of us are in need of your mercy! Amen.”