“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Thanksgiving in the Reign of Christ the King

While American tradition offers thanks in the land of the free and the home of the brave, some still await the promise of freedom with a bravery found in defiant hope.

While American tradition offers thanks in the land of the free and the home of the brave, some still await the promise of freedom with a bravery found in defiant hope.

November 20, 2024 by Father Gordon MacRae

Before celebrating Thanksgiving in America — even if you’re not in America — I will be asking the readers of Beyond These Stone Walls to ponder my post for next week. It has become a Thanksgiving tradition at this blog so I will post it anew on the day before Thanksgiving in America. Some readers have said that it has become a part of their own Thanksgiving observance. Its point is clear. Not everyone lives a privileged life. Not everyone even lives a life in freedom. But in the land of the free and the home of the brave, everyone can find reason to give thanks in the Reign of Christ the King.

The story next week’s post will tell is a true account of history that most other sources left in the footnotes. It is also a story that has deep meaning for us who have endured painful losses in this odyssey called life, the loss of loved ones, the loss of health, of happiness, of hope, the unjust loss of freedom. For some, the litany of loss can be long and painful, and it could drive us all into an annual major holiday depression.

It has helped me and those around me to consider the story of Squanto. History is too often passed down by victors alone. The story of the Mayflower Pilgrims who fled religious persecution (though they didn’t really) to endure the wilds of a brave new world (though they didn’t endure it without help) is well known. But it has been stripped of a far more accurate and inspiring story under its surface.

It is the story of Tisquantum, known to history as Squanto, the sole survivor of a place the indigenous called “The Dawn Land,” now known as Plymouth, Massachusetts. Having been chained up and taken on an odyssey of my own, I found very special meaning in the story of Squanto’s quiet but powerful impact on American history. So will you.

If you have followed our posts, then you know that a spirit of Thanksgiving has been elusive for us behind these stone walls. But with a little time and perspective, my friends here and I find that our list of all for which we give thanks has actually grown in size, scope, and clarity.

From the earliest days of BTSW since its inception in 2009, we have tried to live within a single core principle. I first discovered it in the classic book by Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (Beacon Press 1992). It promotes a fundamental truth about coping with life’s litany of loss with a central liberating theme: “The one freedom that can never be taken from us is the freedom to choose the person we will be in any circumstance.”

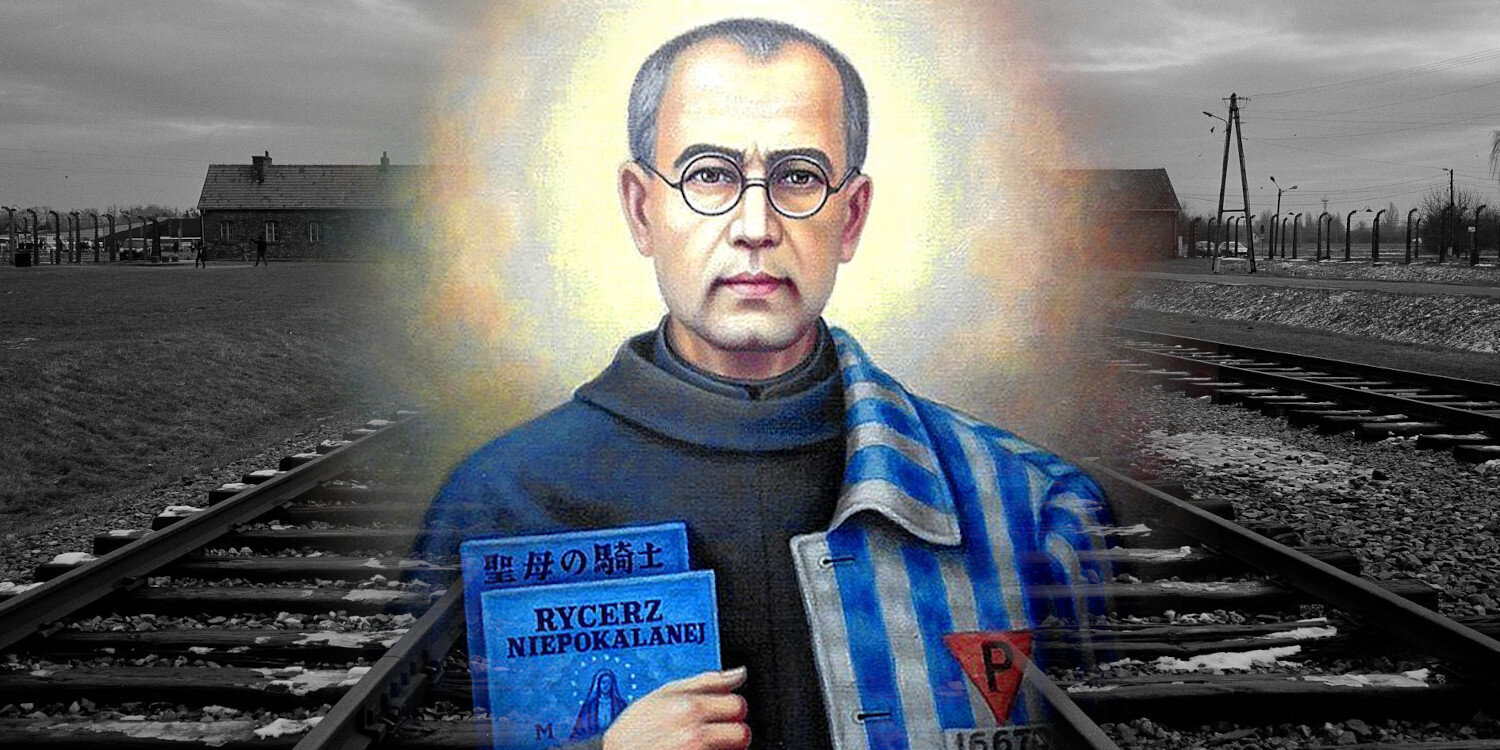

In Frankl’s own words, his story of survival in Auschwitz, the darkest of prisons, was in part inspired by the same person who inspires us. Saint Maximilian Kolbe was a prisoner, but he was first and foremost a Catholic priest who survived heroically by giving his life to save another. “Survived” might seem a strange word to use. Father Maximilian Kolbe was murdered, his earthly remains reduced to smoke and ash to drift in the skies above Auschwitz.

But he survives still. I am certain of this. The Nazi commandant whose power over others extinguished countless lives is now just a footnote on history. I don’t even know his name. But Saint Maximilian lives forever among the communion of saints. He lives in mysterious communion with us behind these stone walls with the same truth that inspired Victor Frankl to survive Auschwitz and write his own story of survival:

“We must never forget that we also find meaning in life even when confronted by a hopeless situation. For what then matters is to bear witness to the uniquely human potential to turn a personal tragedy into a triumph. When we are no longer able to change a situation … we are challenged to change ourselves.”

— Man’s Search for Meaning, p. 116

A friend recently sent me a revision of the famous “Serenity Prayer.” It struck me as an awesome truth and I reposted it a while back in another post, God, Grant Me Serenity. I’ll be Waiting. I find myself sharing this revised version often now with prisoners who come to me with a litany of grief and sorrow:

“God grant me Serenity to accept

the people I cannot change,

The Courage to change

the only one I can,

And the Wisdom to know

that it’s me.”

The Folly of Living with Resentment

One of the two patron saints who empower this blog is Saint Maximilian Kolbe. I have been very much informed by the course of his life in light of his sacrifices. Today my priesthood feels meaningless unless I don the glasses that Father Maximilian wore in prison. If I cannot see what he saw, then what I suffer is meaningless and empty.

But I have seen it. You may recall our post just a week ago, “Thailand’s Once-Lost Son Was Flag Bearer for the Asian Apostolic Congress.” You may have noticed the top graphic on that post. My friend, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri, was wearing a very special shirt sent to him in Thailand by one of our readers. It says “Without sacrifice there is no love.” The quote is attributed to Saint Maximilian Kolbe, and the shirt is emblazoned with his Auschwitz prison number, 16670. I told Max that if he puts this T-shirt on, he will never see his life and suffering the same way again. So I marvel at the fact that he not only put it on, but he wore it for all the world to see.

Sometimes readers write to ask me how it is that I am still (relatively?) sane after 30 years of unjust imprisonment with continually rising and then falling hope. They ask how it is that I still have faith, and why I do not seem to be bitter or resentful when I write. But I HAVE been bitter and resentful about the losses and sorrows life has tossed at me. It is just that I came to recognize that living in anger and resentment is like mixing a toxic brew for our enemies and then drinking it ourselves. It is to live in a self-imposed prison, a relentless assault upon your very soul.

Once you become ready to let go of bitterness and cease to be governed by resentment, faith and hope are what grow in its place. It is like a plant that springs up from a tiny crack in the urban concrete. You simply cannot hold onto your bitterness and your faith at the same time. One of them always gives way to the other.

I find lots of inspiration for this from the readers of this blog. Consider Fr William Graham of the Diocese of Duluth, Minnesota who spent eight years in exile, publicly shamed and his priestly ministry suspended. I wrote of his plight and its most recent development in “After Eight Years in Exile Fr William Graham Is Credibly Innocent.”

He had been falsely accused and cast out in 2016 after his bishop deemed a nearly 40-year-old claim against him to be “credible.” “Credible” is a vague and much abused term used in no other setting but American Catholic priesthood in the age of suspicion. As a legal standard, it means no more than the fact that a priest and an accuser lived in the same geographic area 30, 40, or 50 years ago. If an accusation “could have happened,” then it is seen by our bishops and their lawyers and insurers as “credible.”

After eight years in exile with a dark cloud of accusation hanging over his head, Father Graham was fully exonerated. He returned to ministry in the parish from which he was banished. He returned just in time to file his request for retirement and he moved on to a safer, quieter life with his priesthood intact. In spite of all that befell him, Father Graham believes that he has much to be thankful for. Throughout, Father Graham reported that he found both solace and hope in Beyond These Stone Walls, and it was a lantern during his darker times. Now he is free.

My Thanksgiving for Irony

And I am also thankful for the inspiration of irony. If you have been reading our posts all along, our stories are filled with it. Here’s a very moving example sent to me from a dear reader, the late Kathleen Riney. Kathleen was a retired nurse living in Texas. Her beloved husband, Tom, died from cancer, and Kathleen wrote that she found spiritual refuge in Beyond These Stone Walls.

Before her own death Kathleen wrote to me near the September 23 feast day of Saint Padre Pio, which is also the anniversary of my false imprisonment. I had written a post then that included the “Prayer after Communion” composed by Saint Padre Pio. I sent the post and prayer to Kathleen Riney who was caring for her dying husband at home.

Kathleen wrote that while her husband, Tom, was in the last weeks of his life, she gave him a copy of that prayer printed from that older post. The downloaded page had her name and email address at the top. She had rented a reclining hospital chair to help keep her husband comfortable. Many months after Tom died, Kathleen received this message in her email:

“Kathleen, my name is Kristine. I rented a hospital recliner. I found a paper with the “Stay With Me, Lord” prayer in the chair. I wanted to let you know that the prayer has helped me. I’m scheduled for surgery on November 1st and the surgery is the reason I rented the chair. Somehow that prayer found me and has strengthened me. I wanted to let you know that you touched a stranger in a great way!!! I will read it often. I hope all is well in your life. Thank you, Kristine.”

Accounts such as this are easy to dismiss as mere coincidence, but only if you really struggle to live life only on the surface without ever delving into what I recently called “the deep unseen” in the great Tapestry of God where our lives, through grace, become entangled with the Will of God. Padre Pio had many spiritual gifts in this life that I do not fully comprehend. I wonder if he ever thought that his “Prayer after Communion” would become like a message in a bottle cast into the sea where it would drift into the hands of someone known only to God. Here is that prayer in its entirety:

Padre Pio’s Prayer after Communion

Stay with me, Lord, for it is necessary to have You present so that I do not forget You. You know how easily I abandon You.

Stay with me, Lord, because I am weak and I need Your strength, that I may not fall so often.

Stay with me, Lord, for You are my life, and without You, I am without fervor.

Stay with me, Lord, for You are my light, and without You, I am in darkness.

Stay with me, Lord, to show me Your will.

Stay with me, Lord, so that I hear Your voice and follow You.

Stay with me, Lord, for I desire to love You very much, and always be in Your company.

Stay with me, Lord, if You wish me to be faithful to You.

Stay with me, Lord, for as poor as my soul is, I want it to be a place of consolation for You, a nest of love.

Stay with me, Jesus, for it is getting late and the day is coming to a close, and life passes; death, judgment, eternity approaches. It is necessary to renew my strength, so that I will not stop along the way and for that, I need You. It is getting late and death approaches. I fear the darkness, the temptations, the dryness, the cross, the sorrows. O how I need You, my Jesus, in this night of exile!

Stay with me tonight, Jesus, in life with all its dangers. I need You.

Let me recognize You as Your disciples did at the breaking of the bread, so that the Eucharistic Communion be the Light which disperses the darkness, the force which sustains me, the unique joy of my heart.

Stay with me, Lord, because at the hour of my death, I want to remain united to You, if not by communion, at least by grace and love.

Stay with me, Jesus, I do not ask for divine consolation, because I do not merit it, but the gift of Your Presence, oh yes, I ask this of You!

Stay with me, Lord, for it is You alone I look for, Your Love, Your Grace, Your Will, Your Heart, Your Spirit, because I love You and ask no other reward but to love You more and more.

With a firm love, I will love You with all my heart while on earth and continue to love You perfectly during all eternity.

Amen

This coming Sunday, the Sunday before Thanksgiving, the Church celebrates a most important Solemnity. Our politics consume all the press right now, and it is unavoidable. Only one truth is necessary this Thanksgiving. No matter who we elected president, Christ is our King!

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Whether we face the aftermath of our political struggles with sorrow or joy, our coming Thanksgiving requires a heart open to grace. Here are a few posts that I hope might light that lantern:

Four Hundred Years Since That First Thanksgiving

To Christ the King Through the Immaculate Heart of Mary

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

A Parable of Divine Mercy: Pornchai Moontri has a first birthday in freedom on September 10. One third of his life passed in a prison cell with a Catholic priest.

A Parable of Divine Mercy: Pornchai Moontri had a first birthday in freedom on September 10. One third of his life passed in a prison cell with a Catholic priest.

September 8, 2021

Jesus taught in parables, a word which comes from the Greek, paraballein, which means to “draw a comparison.” Jesus turned His most essential truths into simple but profound parables that could be easily pondered, remembered, and retold. The genre was not unique to Jesus. There are several parables that appear in our Old Testament. I wrote of one some time ago — though now I cannot recall which post it was — about the Prophet Jonah.

The Book of Jonah is one of a collection of twelve prophetic books known in the Hebrew Scriptures as the Minor Prophets. The Book of Jonah tells of events — some historical and some in parable form — in the life of an 8th-century BC prophet named Jonah. At the heart of the story, Jonah was commanded by God to go to Nineveh to convert the city from its wickedness. Nineveh was an ancient city on the Tigris River in what is now northern Iraq near the modern city of Mosul. It was the capital of the Assyrian Empire from 705-612 BC.

Jonah rebelled against the command of God and went in the opposite direction, boarding a ship to continue his flight from “the Presence of the Lord.” When a storm arose and the ship was imperiled, the mariners blamed Jonah and cast him into a raging sea. He was swallowed by “a great fish” (1:17), spent three days and nights in its belly, and then the Lord spoke to the fish and Jonah “was spewed out upon dry land” ( 2: 10) . ( I could add, as a possible aside, that the great fish might later have been sold at market, but there was no longer any prophet in it!)

Then God, undaunted by his rebellion, again commanded Jonah to go to Nineveh. Jonah finally went, did his best, the people repented, and God saved them from destruction. Many biblical scholars regard this part of the Book of Jonah as a parable. Jesus Himself referred to the Jonah story as a presage, a type of parable account pointing to His own death and Resurrection:

“Some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, 'Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.' But he answered them, 'An evil and adulterous generation asks for a sign, but no sign will be given except the sign of the Prophet Jonah. For just as Jonah was three days in the belly of the giant fish so for three days and three nights, the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth.”

— Matthew 12:38-40

What I take away from the parable part of the story of Jonah is that there is no point fleeing from “the Presence of the Lord.” God is not a puppeteer dangling and directing us from strings. Rather, the threads of our lives are intertwined with the threads of other lives in ways mysterious and profound. I have written several times of what I call “The Great Tapestry of God.” Within that tapestry — which in this life we see only from our place among its tangled threads — God connects people in salvific ways, and asks for our cooperation with these threads of connection.

The Parable of the Priest

I was slow to awaken to this. For too many days and nights in wrongful imprisonment, I pled my case to the Lord and asked Him to send someone to deliver me from this present darkness. It took a long time for me to see that perhaps I have been looking at this unjust imprisonment from the wrong perspective. I have railed against the fact that I am powerless to change it. I can only change myself. I know the meaning of the Cross of Christ, but I was spiritually blind to my own. Ironically, in popular writing, prison is sometimes referred to as “the belly of the beast.”

After a dozen years of railing against God in prison, I slowly came to the possible realization that no one was sent to help me because maybe I am the one being sent. My first nudge in this direction came upon reading one of the most mysterious passages in all of Sacred Scripture. It arose when I pondered what exactly happened to Jesus between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, the three days He refers to in the Sign of Jonah parable in the Gospel of Matthew above. A cryptic hint is found in the First Letter of Peter:

“For it is better to suffer for good, if suffering should be God's will, than to suffer for evil. For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the Spirit, in which he also went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison who in former times did not obey.”

— 1 Peter 3:17-20

The second and much stronger hint also came to me in 2006, twelve years after my imprisonment commenced. This may be a familiar story to long time readers, but it is essential to this parable. I was visited in prison by a priest who learned of me from a California priest and canon lawyer whom I had never even met. The visiting priest was Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan who, unknown to me at the time, had been a postulator for the cause of sainthood of St. Maximilian Kolbe whom I barely knew of.

Our visit was brief, but pivotal. Father McCurry asked me what I knew about Saint Maximilian Kolbe. I knew very little. A few days later, I received in the mail a letter from Father McCurry with a holy card (we could receive cards then, but not now). The card depicted Saint Maximilian in his Franciscan habit over which he partially wore the tattered jacket of an Auschwitz prisoner with the number, 16670. I was strangely captivated by the image and taped it to the battered mirror in my cell.

Later that same day, I realized with profound sadness that on the next day — December 23, 2006 — I would be a priest in prison one day longer than I had been a priest in freedom. At the edge of despair, I had the strangest sense that the man in the mirror, St. Maximilian, was there in that cell with me. I learned that he was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1982, the year I was ordained. I spent a lot of time pondering what was in his heart and mind as he spontaneously stepped forward from a line of prisoners and asked permission to take the place of a weeping young man condemned to death by starvation. I wrote of the cell where he spent his last days in “Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance.”

On the very next day after pondering that man in the mirror on Christmas Eve, 2006 — a small but powerful book arrived for me. It was Man’s Search for Meaning, by Auschwitz survivor, Dr. Viktor Frankl, a Jewish medical doctor and psychiatrist who was the sole member of his family to survive the horror of the concentration camps. I devoured the little book several times. It was one of the most meaningful accounts of spiritual survival I had ever read. Its two basic premises were that we have one freedom that can never be taken from us: We have the freedom to choose the person we will be in any set of circumstances.

The other premise was that we will be broken by unending suffering unless we discover meaning in it. I was stunned to see at the end of this Jewish doctor’s book that he and many others attributed, in part, their survival of Auschwitz to Maximilian Kolbe “who selflessly deprived the camp commandant of his power over life and death.”

The Parable of a Prisoner

God did not will the evil through which Maximilian suffered and died, but he drew from it many threads of connection that wove their way into countless lives, and now I was among them. For Viktor Frankl, a Jewish doctor with an unusual familiarity with the Gospel, Maximilian epitomized the words of Jesus, “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

I asked the Lord to show me the meaning of what I had suffered. It was at this very point that Pornchai Moontri showed up in the Concord prison. I have written of our first meeting before, but it bears repeating. I was, by “chance,” late in the prison dining hall one evening. It was very crowded with no seats available as I wandered around with a tray. I was beckoned from across the room by J.J., a young Indonesian man whom I had helped with his looming deportation. “Hey G! Sit here with us. This is my new friend, Ponch. He just got here.”

Pornchai sat in near silence as J.J. and I spoke. I was shifting in my seat as Pornchai’s dagger eyes, and his distrust and rage were aimed in my direction. J.J. told him that I can be trusted. Pornchai clearly had extreme doubts.

Over the next month, Pornchai was moved in and out of heightened security because he was marked as a potential danger to others. Then one day as 2006 gave way to 2007, I saw him dragging a trash bag with his few possessions onto the cell block where I lived. He paused at my cell door and looked in. He stepped toward the battered mirror and saw the image of St. Maximilian Kolbe in his Franciscan habit and Auschwitz jacket and he stared for a time. “Is this you?” he asked.

Within a few months, Pornchai’s roommate moved away and I was asked to move in with him. Less than four years later, to make this long and winding parable short, Pornchai was received into the Catholic faith on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010. Two years after that, on the Solemnity of Christ the King, 2012, we both followed Saint Maximilian Kolbe into Consecration to Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Most readers likely know by now the depth of the wounds Pornchai experienced in life. He was abandoned as a child in Thailand, suffered severe malnutrition, and then, at age eleven, he fell into the hands of a monster. He was taken from his country and the only family he knew, and was brought to the U.S. where he suffered years of unspeakable abuse. He escaped to a life of homelessness, living on the streets as a teenager in what was to him a foreign land. At age 18, he accidentally killed a much larger man during a struggle, and was sent to prison.

Pornchai’s mother, the only other person who knew of the years of abuse he suffered, was murdered on the Island of Guam after being taken there by the man who abused him. In 2018, after I wrote this entire account, that man, Richard Alan Bailey, was brought to justice and convicted of forty felony counts of sexual abuse of Pornchai. After the murder of his mother at that man’s hands, Pornchai gave up on life and spent the next seven years in the torment of solitary confinement in a supermax prison in the State of Maine. From there, he was moved here with me.

Over the ensuing years, as I gradually became aware of the enormity of Pornchai’s suffering, I felt compelled to act in the only manner available to me. I followed Saint Maximilian Kolbe into the Gospel passage that characterized his life in service to his fellow prisoners: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

I asked the Lord, through the Immaculate Heart of Mary, to free Pornchai from his past and the seemingly impenetrable prisons that held him bound. I offered the Lord my life and freedom just as Maximilian did on that August day of 1941. Then I witnessed the doors of Divine Mercy open to us.

This blog began just then. In the time he spent with me, Pornchai graduated from high school with honors, earned two additional diplomas in guidance and psychology, enrolled in theology courses at Catholic Distance University, and became an effective mentor for younger prisoners in a Fast Track program. He tutored young prisoners in mathematics as they pursued high school equivalency, and, as I have written above, he had a celebrated conversion to the Catholic faith, a story captured by Felix Carroll in his famous book, Loved, Lost, Found.

Pornchai became a master craftsman in woodworking, and taught his skill to other prisoners. One of his model ships is on display in a maritime museum in Belgium. His conversion story spread across the globe. After taking part in a number of Catholic retreat programs sponsored by Father Michael Gaitley and the Marians of the Immaculate Conception, Pornchai was honored as a Marian Missionary of Divine Mercy. So was I, but only because I was standing next to him.

One of the most beautiful pieces of writing that has graced this blog was not written by me, nor was it written for me. It was written for you. It was a post by Canadian writer Michael Brandon, a man I have never met, a man who silently followed the path of this parable for all these years. His presentation is brief, but unforgettable, and I will leave you with it. It is, “The Parable of the Prisoner.”

+ + +

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance

Book: Man’s Search for Meaning

Book: Loved, Lost, Found

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: On September 10, Pornchai will mark his 48th birthday. It is his first birthday in freedom. In 2020 on that date he was just beginning a grueling five months in ICE detention awaiting deportation. For the previous 29 years he was in prison. For the four years before that he was a homeless teenager having fled from a living nightmare.

I asked him what he would like for his birthday, and this was his response:

“I have never seen the ocean. I would like to go to the Gulf of Thailand and visit my cousin who was eight years old when I was eleven and last saw him. He is now an officer in the Thai Navy.”

Please visit our “SPECIAL EVENTS” page, and our BTSW Library category for posts about Pornchai.

For Darryll Bifano, the Currency of Debt Is Mercy

Men facing death in this prison at one time died alone. Darryll Bifano is a prisoner and hospice volunteer who helped change that. In the process, he changed himself.

Men facing death in this prison at one time died alone. Darryll Bifano is a prisoner and hospice volunteer who helped change that. In the process, he changed himself.

Some time ago, I wrote a Scripture post that ended up being about death and thus scared some people off from reading it. Everyone has to face it, but few want to, and many spend their lives in denial of it. That post was, “The God of the Living and the Life of the Dead.” Despite its heavy dose of theology, it drew an unusual audience for Beyond These Stone Walls and was shared some 5,000 times on Facebook and other social media. Death touches everyone.

There was a pall over this prison as summer commenced this year. One of our friends, John, age 39, died of pancreatic cancer in the prison medical unit on June 10. It was a long and grueling death that saw him drift from the vibrancy of a healthy man in his thirties to an emaciated frame of his former self. Through it all, his alert mind grasped for meaning and connection.

There was a time when prisoners here died in empty isolation. Several years ago, one of my own roommates, 52-year-old Harvey, developed stomach cancer that slowly consumed his life. When he could no longer live among us, he died alone locked in a cold, bare room with four concrete walls and little human contact.

I pleaded at the time to visit Harvey and help take care of him but overwhelmed prison medical staff responded that there was just no process in place that allows for that. But in the last three years here, this has dramatically changed. A group of men — prisoners all — have come together to form a training protocol for a hospice team. Now in three-hour shifts around the clock, they sit, talk, walk and care for fellow prisoners who are dying.

My first deeply-felt gratitude to this hospice team came when our friend, Anthony Begin, died from cancer. I wrote of that journey in a post that shocked some readers. It was “Pentecost, Priesthood, and Death in the Afternoon.” I wrote about how Anthony was such a caustic personality, that I literally threw him out of my room one day. We did not speak for over a year until Pornchai Moontri told me one day that Anthony is dying.

Pornchai and I took over the care of Anthony, and in the process, he changed. So did we. Anthony was allowed to live in a bunk just outside our cell for his final months. When his condition came to the point of no return, we had to leave him in the medical unit where we would never see him again.

This was my first experience of the immense value of hospice. The newly formed prisoner hospice team was with Anthony around the clock for the final steps of his journey which I documented in “The First of the Four Last Things.” Thanks mostly to the influence of Pornchai Moontri, Anthony experienced a religious conversion and was received into the Catholic faith just before we handed him over to hospice.

I will never forget what happened a week after he died. It turned out that Anthony left this life having committed a second crime against the State of New Hampshire: an unreturned library book. When a prisoner leaves without returning a book, an alert comes across a computer screen at my desk in the prison library. Here is what the computer told me a week after Anthony died:

“Anthony Begin — Released with book #3015: Heaven is for Real.”

A Down Payment on a Debt

The recent, untimely death of John at age 39 unsettled many prisoners and sent a shockwave throughout this prison. John was a young man in good shape until he began having symptoms of discomfort. Once the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer came, the end loomed shockingly fast. His final weeks were not easy, but he was never alone thanks to the dedication and perseverance of a few good men.

One of these men is Darryll Bifano. If his name sounds a bit familiar, it’s because you have met him before in these pages. Darryll was a pitcher on Pornchai Moontri’s intramural softball team, the Legion of Angels when it won the league pennant for the third year in a row in 2016. At 6’3” and 270 pounds, Darryll Bifano was an imposing presence both on the team and in my post, “A Legion of Angels Victorious.”

A big guy with a wide wingspan not much got past Darryll on the pitcher’s mound. He proved himself to be a team player who contributed much to our victories. Today, Darryll lives on the pod Pornchai Moontri and I moved to last summer. He was among those who spoke up for us and helped us to get there.

During the long ordeal of Darryll’s ministering to John in hospice, I was much aware of the schedule he had to keep. He has a full-time job working in the prison Recreation Department — the same place where Pornchai works. Darryll also volunteers for multiple other programs offering support to prisoners in need. He is a trained volunteer for a newly formed Peer Support program that assists with monitoring and moral support for prisoners on suicide watch, a critical and important need here.

Darryll’s presence in that endeavor seemed to naturally grow out of his commitment to hospice. Having witnessed the physical and emotional toll that hospice can exact from these men, I sat down with Darryll after the death of John. We spent time processing not only the experience but also the journey that brought Darryll to this point in his life.

We began with the most natural question of all. What brought Darryll Bifano to care for the dying through hospice? I have to let him answer this in his own words:

“I am 47 years old and in the 11th year of a 27-year-to-life sentence for second degree homicide. I grew up in the ideal American family: a loving mother and father, a brother and a sister. I am the oldest. I excelled in school and in multiple sports, graduated from two universities, and followed my passion for music, and traveled that road everywhere and anywhere it would take me.

“Through trial and error and experience, I was becoming the man I always wanted to be. I was on a path of my choosing, and as a musician I developed some talent. Then everything changed in a single foggy moment. After a night of drinking and drugs, my best friend and I argued. Then we fought. I threw a single punch that killed my dear friend, Stephen, and, in the aftermath of our drunken state, he died alone.

“I work with hospice today because I have a debt to life that I cannot fully pay, but I must try. I cannot bring back my friend, but I can honor him, and be responsible, and give this tragedy meaning.”

Darryll is one of 20 prisoners, each working in 3-hour shifts, who sit with terminally ill prisoners and accompany them to the end of life. After working all day, he often takes a shift that no one else really wants — from 1:00 to 4:00 AM. A quick two hours sleep and then Darryll is up again to get ready for his work at 7:00 AM.

I have seen this schedule take its toll on Darryll, but like the few prisoners who stand out dramatically here, he seems driven by service, and the sure knowledge that mercy was shown to others is the path to peace within himself:

“I remember, as a child, the experience of my grandfather dying of cancer in his home. This drove home fore me the importance of not dying alone.

“In hospice, you’re sitting with this guy and he is dying, and it’s treated as taboo — on one else really wants to talk about it. It’s the final stage of life.

“In prison, I often hear people say, ‘I came in alone and I’ll go out alone.’ It’s their excuse for disengagement with the world around them, but I no longer believe in this. For a life that has meaning, no one can make it alone in this world.”

Is God Dead?

In the last week of John’s life, Darryll spent about eight shifts with him, mostly in the pre-dawn hours which often seemed the toughest for John. Darryll described this time as “the ideal of what hospice is supposed to be.” He walked with John from resentment and denial to acceptance. They talked of John’s life, his family, nieces, and nephews. Darryll sat and wrote letters to them dictated by John. Along the way, Darryll was witness to a transition from torment to peace.

I am not certain that Darryll phrased this as such in his own mind, but his presence to John fulfilled a basic tenet of Viktor Frankl’s famous book, Man’s Search for Meaning. Darryll was helping John to give meaning to suffering, perhaps the greatest gift one human being can impart to another in the face of death.

For much of his life, John had reportedly described himself first as an atheist, and then, in more recent years, an agnostic. In its simplest form, agnosticism is to render the question of God moot because, for the agnostic, it is impossible to know Him or whether He even exists so there is no point trying.

As I sit here typing this post, the last book John read in this life has just landed on my desk to be checked back into the library. It’s a collection of essays by the Nineteenth Century German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche.

I cannot imagine what prompted John to request this book, but the reality was that in his dying state he was unable to read at all. He handed the book to his hospice volunteers. Caring for him in their 3-hour shifts, he tasked them to read aloud portions of Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spake Zarathustra) Nietzsche’s treatise about the death of God.

Nietzsche developed the essay between 1883 and 1885 to explain his theory of the Übermensche (meaning superman or overman). Stating that “God is dead,” Nietzsche rejected Christian beliefs and traditional values as the source of our “collective slave morality.” Instead, Nietzsche believed in the power of superman: a person of extraordinary imagination and will who can break the destructive grip of traditional Christian values.

Only a superman, Nietzsche theorized, can institute a “master morality” to save society from the slavery of Christianity. This became the foundation for Adolf Hitler’s concept of a Master Race. It was also the foundation of the effort to dissolve Christian influence in Western Civilization that I recently described in these pages in “Fathers Day in the Land of Nod.”

This was the last book John requested of me, and it was perhaps the very last book I might have sent him in the week of his death had I been given a choice. But alas, such choices are not mine to make. Nor are they Darryll Bifano’s who dutifully read aloud Nietzsche’s words to John.

I remember once writing in these pages about the resurgence of Nietzsche’s “God is Dead” movement in the 1960s. The bumper stickers were everywhere in that radical, “question everything” age of my adolescence in 1968: “GOD IS DEAD! Signed, Nietzsche.” Then one day I saw one that presented a sobering thought: “NIETZSCHE IS DEAD! Signed, God.”

Even Nietzsche, an atheist, in the end, came to regret the impact of his own atheistic thought. He wrote that the destruction of the belief in God in the 20th Century was the greatest cataclysm humanity has ever faced: “What were we doing when we unchained this Earth from its Sun? ” he asked. “Are we not now straying as though through an infinite nothing?”

But while Darryll was reading to John, he also took questions, and these were perhaps more revealing of what was taking place in the heart and soul of a man facing death while his mind struggled with its apparent emptiness. John stopped Darryll in his reading and asked, “Do you think there is a heaven? Do you think I could go there?”

Perhaps John wasn’t buying the emptiness of Nietzsche’s ode to the dying. Perhaps Darryll wasn’t buying it either, and this post is actually more about him. He is not a man who should forever be defined by his one big mistake. He is a good man, a talented and dedicated asset to the race we call “human.”

Darryll’s footprints here leave this a better place. God knows, prison very much needs natural leaders like Darryll Bifano who draw others along a path to righteousness having long since parted ways with his own personal road to ruin.

Last summer in my post, “The Days of Our Lives,” I wrote about a concert that Darryll helped organize among the musicians here. It was worthy of Carnegie Hall, and its most unforgettable moment was Darryll’s brilliant performance of Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.”

Darryll didn’t offer me his answers to John’s last questions: “Do you think there is a heaven? Do you think I could go there?” “I grew up a Catholic,” Darryll told me, “and like so many of the wannabe rebels of my time, I left my faith back there.”

“Is the door to it closed or cracked?” I asked. “Well…” he pondered with a distant gaze, “I always really do enjoy talking to you, G.”

+ + +

Note: On February 17, 2023 Darryll Bifano was profiled on the television news and cultural magazine, New Hampshire Chronicle.

Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part Two

. . . The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us. Within days of reading Man's Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe's sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue. . . .

See Maximilian and This Man's Search for Meaning Part OneAs a young priest in 1982, I was only vaguely familiar with the name Maximilian Kolbe. I remember reading of his canonization by Pope John Paul II, but Father Kolbe's world was far removed from my modern suburban priestly ministry. I was far too busy to step into it.I didn't know that nearly two decades later, Father Kolbe's life, death, and sainthood would be proclaimed on the wall of my prison cell. I also didn't know this would help define the person I choose to be in prison.Being a Jew and not a Catholic, Dr. Viktor Frankl in Man's Search for Meaning, said nothing about Maximilian's sainthood or any miracles attributed to his intercession. Instead, Dr. Frankl was moved by the profound charity of Maximilian, which defied the narcissism of our times.For those unfamiliar with him, the story is simple.The prisoners of Auschwitz were packed into bunkers like cattle. To encourage informants, the camp had a policy that if any prisoner escaped, 10 others would be randomly chosen for summary execution.At the morning role call one day, a prisoner from Maximilian's bunker was missing. Guards chose 10 men to be executed. The 10th fell to the ground and cried for the wife and children he would never see again. Father Kolbe spontaneously stepped forward and said,

"I am a Catholic priest, and I would like to take the place of this man."

Two weeks later, he alone was still alive among the 10 prisoners chained and condemned to starvation. Maximilian was injected with carbolic acid on August 14, 1941, and his remains unceremoniously incinerated.For the unbeliever, all that Maximilian was went up in smoke. Viktor Frankl shared some other corner of that horrific prison. The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us.Within days of reading Man's Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe's sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue.Conventual Franciscan Father Jim McCurry had been in an airport in Ireland when he heard an Irish priest nearby mention that he corresponds with a priest in a Concord, New Hampshire prison. Father McCurry said he was on his way to visit his order's house in Granby, Massachusetts and would arrange to visit the Concord prison.Weeks later, Father McCurry and I met in the prison visiting room. When I asked him what his "assignment" is, he said,

"Well I just finished a biography of St. Maximilian Kolbe. Have you heard of him?"

Father McCurry went on to say that he was involved in Father Maximilian's cause for sainthood. He had met the man whose great grandfather life was saved by Father Kolbe.A few years later, Father McCurry arranged a Father Maximilian Kolbe exhibit at the National Holocaust Museum. It was then that he sent me the card depicting Father Maximilian clothed in his Franciscan habit with one sleeve in his prison uniform. I keep the card above my mirror in my cell.I can never embrace these stone walls. I can't claim ownership of them. Passively acceding to injustice anywhere contributes to injustice everywhere. Father Maximilian never approved of Auschwitz.One can't understand how I now respond to these stone walls, however, without hearing of Father Maximilian's presence there.

Above my mirror, he refocused my hope in the light of Christ. The darkness can never overcome it.

What hope and freedom there is in that fact! The darkness can never, ever, ever overcome it!Please share with me your comments below in the comments area.

Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part One

. . . At the very end of his book, Dr. Frankl revealed the name of his inspiration for surviving Auschwitz. He wrote of Sigmund Freud's cynical view that man is self-serving. And a man's instinctual need to survive will trump "quaint notions" such as grace and sacrifice every time. For Dr. Frankl, Auschwitz provided the proof that Freud was wrong. That proof is Father Maximilian Kolbe. . . .

How I came to be in this prison is a story told elsewhere, by me and by others. How I "met" Father Maximilian Kolbe 60 years after he surrendered his life at Auschwitz is a story about actual grace. In his Catholic Catechism, Jesuit Father John Hardon defines actual grace as God's gift of "the special assistance we need to guide the mind and inspire the will" on our path to God. Sometimes, it's very special.

My first three years in prison are a blur in my memory. There is no point trying to find words to express the sense of loss, of alienation, of being cast into an abyss that was not of my own making -- a loss that could not be grounded in any reality of mine.

About 1,000 days and nights passed in the abyss before what Father Hardon described as "special assistance" crossed my path.

Someone, somewhere -- I don't know who -- sent the prison's Catholic chaplain (a layman then) a book entitled Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, M.D. Somewhere in my studies, I heard of this book, but only a prisoner can read it in the same light in which it is written. The chaplain called me to his office. He wanted to know whether he should recommend this book, but didn't have time to read it. He wanted my opinion.

It had been three years since anyone had asked my opinion on anything. I didn't read Dr. Frankl's book so much as devour it. I read it through three times in seven days. As a priest, I often preached that grace is a process and not an event. It is not always so. I was meant to read Man's Search for Meaning at the precise moment that it landed upon my path. A week earlier, I would not have been ready. A week later may have been too late.

I was drowning in the solitary sea of deeply felt loss. I was not going to make it across. My priesthood and my soul were dying. The book, as I have come to call it, is Viktor Frankl's vivid account of how he was alone among his family to survive imprisonment at Auschwitz. This was an imprisonment imposed on him for who he was: a Jew.

There is a central message in this small book. A profound message, so clear in meaning, that it has within it the hallmark of inspired truth. Like Saul thrown from his mount, I remember sinking to the floor when I read it.

"There is a freedom that no one can ever take from you: The freedom to choose the person you are going to be in any set of circumstances."

This changed everything. Everything! You will see how later. At the very end of his book, Dr. Frankl revealed the name of his inspiration for surviving Auschwitz. He wrote of Sigmund Freud's cynical view that man is self-serving. And a man's instinctual need to survive will trump "quaint notions" such as grace and sacrifice every time. For Dr. Frankl, Auschwitz provided the proof that Freud was wrong.

That proof is Father Maximilian Kolbe.

To be continued in Maximilian and This Man's Search for Meaning Part TwoPlease share your thoughts below in the comment area.