“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

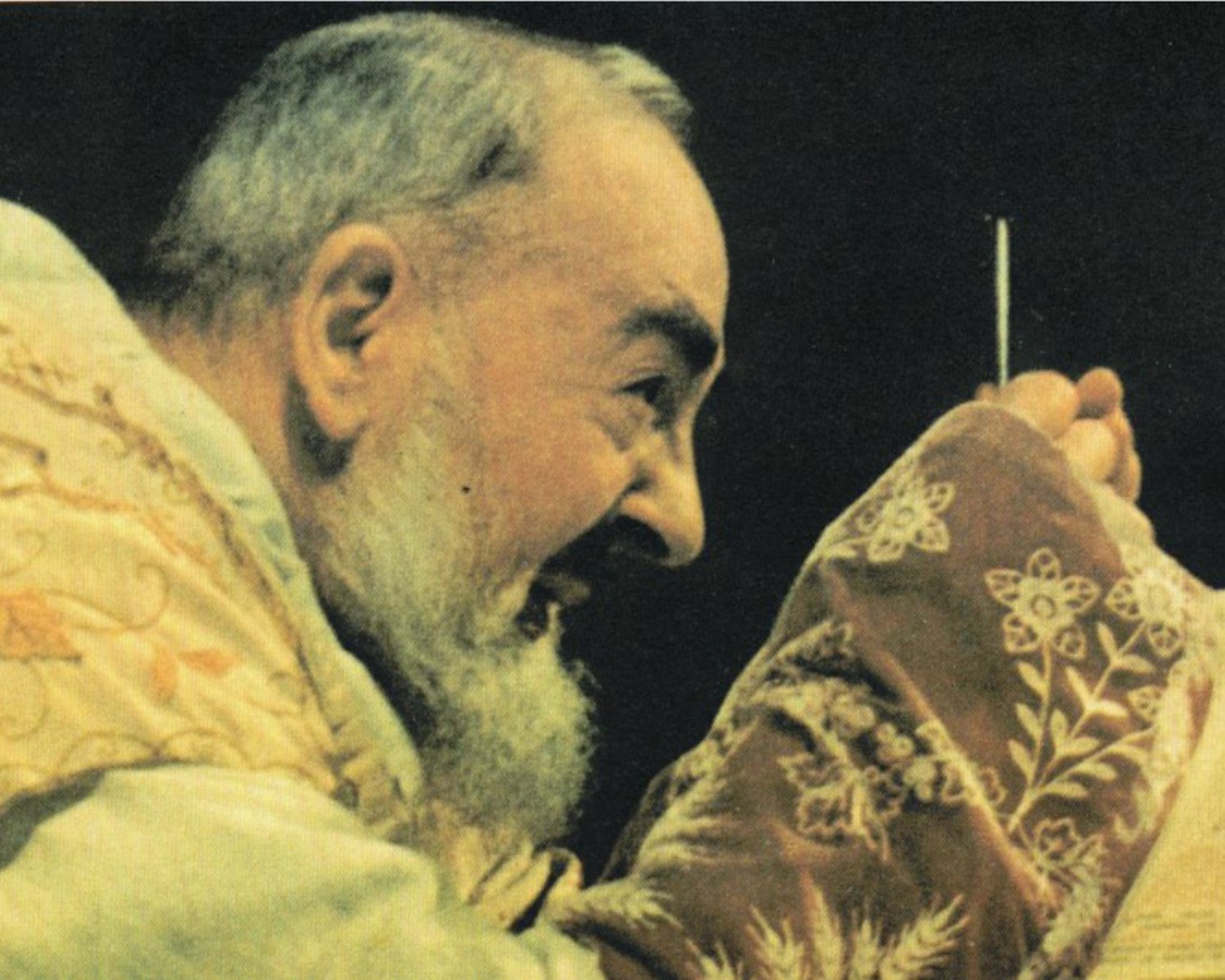

With Padre Pio When the Worst That Could Happen Happens

Inspired by Padre Pio's surrender to sacrificial suffering, this priest wrongly imprisoned for 28 years still sees signs and wonders even in life's darkest days.

Inspired by Padre Pio’s surrender to sacrificial suffering, this priest wrongly imprisoned for 29 years still sees signs and wonders even in life’s darkest corners.

September 21, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

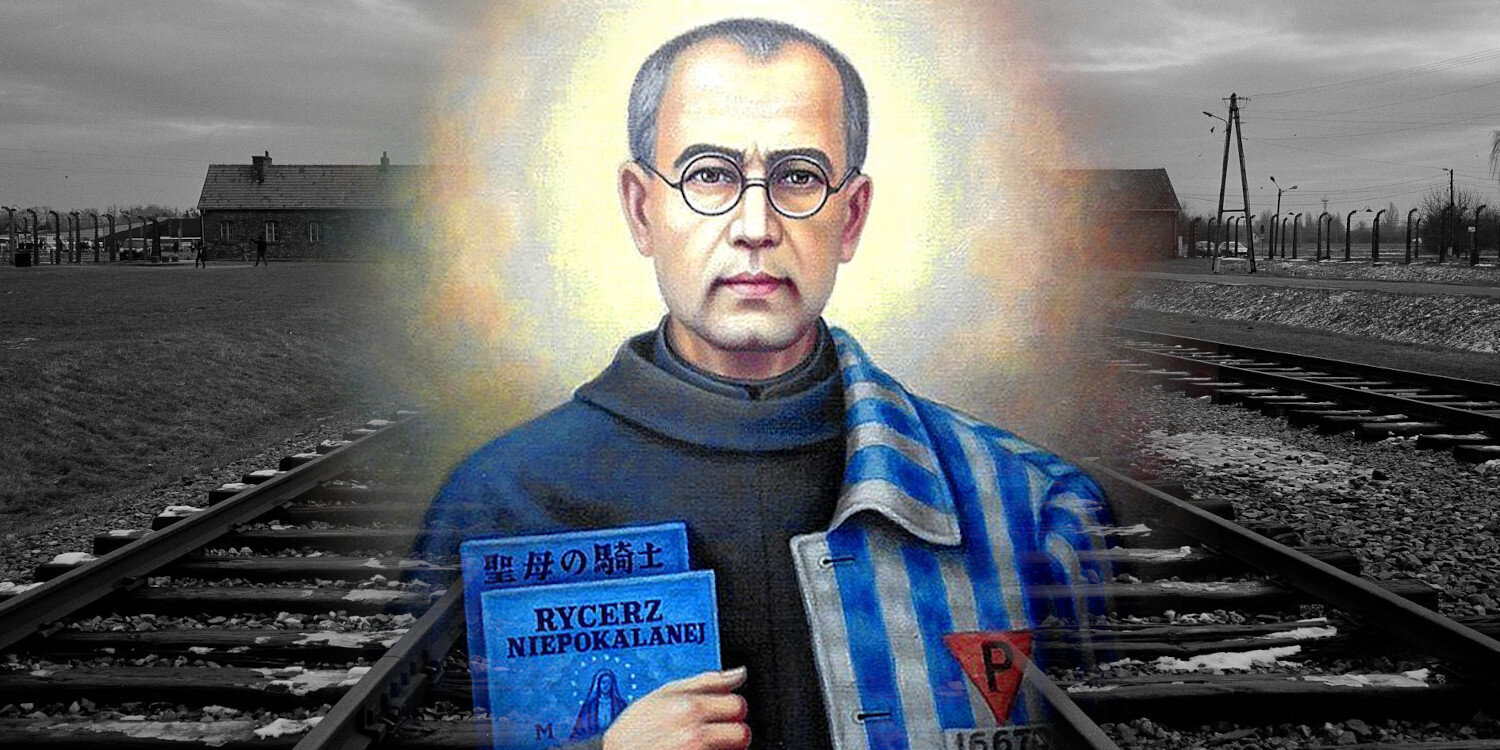

I write this week in honor of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina, more popularly known as Padre Pio. He is one of the two Patron Saints of Beyond These Stone Walls and one who has had a living presence in my life behind these walls. The other, of course, is Saint Maximilian Kolbe. Pornchai Moontri and I share a somewhat mystical connection with both. A little time spent at “Our Patron Saints” in the BTSW Public Library might demonstrate how they have come to our spiritual aid in the darkest times of our lives here.

Though they were 20th Century contemporaries, Padre Pio and Maximilian Kolbe did not know each other except by reputation. Among the many letters of Padre Pio to pilgrims who wrote to him are several in which he urged suffering souls to enroll in the Militia of the Immaculata and Knights at the Foot of the Cross, the two spiritual movements founded by Maximilian Kolbe. I stumbled upon this after Pornchai Moontri and I enrolled in both. It is ironic that both saints were canonized by another saint. The lives of St. Padre Pio, St. Maximilian and St. John Paul II were lived with heroic virtue even as they suffered. I wrote of the latter two in a recent post that touched the hearts of many: “A Tale of Two Priests: Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul II.”

Padre Pio also had a global reputation for doing remarkable things, but he did them in the midst of remarkable suffering. After bearing the wounds of Christ for a half century he passed from this life on September 23, 1968, the date upon which the Church now honors him. On that same date, 26 years later, I was wrongly convicted and sent to prison for life after having tossed aside three chances to save myself and my freedom with a lie.

Since that day, September 23, 1994, Padre Pio has injected himself into my life in profoundly grace-filled ways. I have written of these encounters in multiple posts, but the two that seem to stand out the most are “Padre Pio: Witness for the Defense of Wounded Souls” and one that delves into the deeper mysteries of his life and death, “I Am a Mystery to Myself! The Last Days of Padre Pio.” We will link to them again at the end of this post and invite you to read them in his honor this week.

Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane

As long as our lives are tied to this world, we will never resolve the mystery of suffering. Like so many of you, I, too, have been confronted with the paradox of suffering. We are trapped in it because, unlike God, we live a linear existence. We see only what has come before and what is now, but we can only imagine what is to come.

But God lives in the '“nunc stans,” the “eternal now” seeing all at once our past, present, and future. Some believers expect God to be the Director of the play that is our lives, but He is more a participant than a director. He allows suffering as a means toward a specific end, but the end is His and not necessarily ours. In my post, “Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane,” Jesus discovers that the very first of his suffering is that he is inflicted with a human heart. He asks God to take away the great suffering that is to come, “but Thy will be done.” It is an aspect of the truth of the Resurrection that Jesus brought both His Divinity and the human heart with him when He opened the Kingdom of Heaven to us.

I have encountered this same paradox about suffering, and did so again on the night before writing this post. It comes in the night as a nagging litany of “What-Ifs.” It consists of a series of inflection points, points at which, in my own history, my current state in life could have been avoided had I turned left instead of right. I have identified about five such times and places in my life when a different decision would likely have prevented all the unseen suffering that was to follow.

But “What-Ifs” are spiritually unproductive. They deny the sacrificial nature of at least some of what we suffer and they disregard the plan God has for our souls. During my most recent nighttime Litany of “What-Ifs,” I was reminded of that prayer by St. John Henry Newman that I wrote about in “Divine Mercy in a Time of Spiritual Warfare”:

“God has created me to do Him some definite service. He has committed some work to me which he has not committed to another. I have my mission. I may never know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next …”

I do not have the gift of foresight, but my hindsight is clear. Had I allowed myself to take any of those five alternate steps that I have been reminiscing about, then the work committed to me and no other could not have taken place, and a life and soul may have been lost forever. That life and soul became important to me, but only because it was a work God committed to me and no one else. It was the life and soul of my friend, Pornchai whom God has clearly called out of darkness. It is my great honor to have been an instrument of the immense grace that transformed Pornchai, but to be such an instrument means never to ask,”What was in it for me?”

So, if given the chance now, would I trade Pornchai’s life, freedom, and soul to erase the last 28 years of my own unjust imprisonment and vilification? Our Lord answered that question with one of his own: “What father among you would give his son a stone if he asks for bread?” (Matthew 7:10). This verse is followed just a few verses further by one that I wrote about recently in “To the Kingdom of Heaven Through a Narrow Gate”:

“Enter through the narrow gate, for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it.”

— Matthew 7:13-14

I could not have foreseen any meaning in what I suffered during my own agony in the garden. Such clarity is only in hindsight. Being sent to prison on false charges seemed to me the worst thing that could ever happen to a person — certainly the worst that could ever happen to a priest because a priest in such a circumstance is almost equally reviled by both Church and State. But today, when recognition of the alternative dawned — recognition that the life and soul of my friend would have been lost forever — I find that I can bear this suffering. I do not choose it. It chose me.

When Padre Pio Stepped In

The story of how Padre Pio stepped into my life as a priest and prisoner came also through Pornchai Moontri. Like Padre Pio himself, I had been shunned and vilified by Catholic activists in groups like S.N.A.P. and V.O.T.F. Out of fear, many other priests and Church officials joined in that shunning during my first decade in prison. The police, the courts, the news media, and the rumor mill in my diocese all amounted to a perfect storm that I was powerless to overcome. In 2002, the storm became a hurricane, first in Boston, then in New Hampshire and from there across the country.

In 2005, The Wall Street Journal’s explosive 2-part publication of “A Priest’s Story” altered the landscape. After it was published, Catholic League President Bill Donohue reached out to me with an invitation to write an article for the Catholic League Journal, Catalyst. My article, “Sex Abuse and Signs of Fraud” was published in the November 2005 issue.

When I received that month’s issue, I was more stricken by its front-page revelation than with my own centerpiece article. It was “Padre Pio Defamed.” I was shocked to learn, for the first time, that Padre Pio suffered more than the visible wounds of the crucified Christ. He also suffered a cascade of slander from both secular and church officials with wild suspicions and accusations that he sexually abused women in the confessional resulting in multiple Church investigations. In 1952, the Congregation of the Holy Office placed in its Index of Forbidden Books all books about Padre Pio.

Heaven can be most forgiving. The bishop who suspended the priestly faculties of Padre Pio based on the rapid spread of false information was Bishop Albino Luciani. Just a few weeks ago after a miracle attributed to his intercession was confirmed, he was beatified as Blessed Pope John Paul I.

It is ironic — not to mention boldly courageous — that Pope John Paul II canonized Padre Pio in 2002 at the height of media vitriol during the clergy abuse scandal in the United States. One of the last investigations against Padre Pio was a 1960 report lodged by Father Carlo Maccari alleging, with no evidence, that Padre Pio had sexual liaisons with female penitents twice per week.

In the same month my Catalyst article was published, Tylor Cabot joined the slander in the November 2005 issue of Atlantic Monthly with “The Rocky Road to Sainthood.” He wrote, “despite questions raised by two papal emissaries — and despite reported evidence that [Padre Pio] raised money for right-wing religious groups and had sex with penitents — Pio was canonized in 2002.”

Fr. Maccari’s original slander also found its way into The New York Times. Maccari went on to become an archbishop. On his deathbed, Maccari recanted his story as a monstrous lie born of jealousy. He prayed on his deathbed for the intercession of Padre Pio, the victim of his slander.

A Heaven-Sent Blessing from Padre Pio

Also in November of 2005, Pornchai Moontri arrived in this prison after his experience of all the events I described in “Getting Away with Murder on the Island of Guam.” Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio teamed up to reverse in him a road to destruction in ways that I was powerless to even imagine. A few years later, in 2009, this blog was born and some of my earliest posts were about what Padre Pio and Maximilian Kolbe suffered in life on the road to becoming the spiritual advocates they have been for us and millions of others. Just after I wrote about Padre Pio for the first time, I received a letter from Pierre Matthews from Ostend, Belgium who had been writing to me since reading of me in The Wall Street Journal.

Learning of my faith despite false charges and imprisonment became for Pierre the occasion for his return to faith and the Church after a long European lapse. When he read my early posts about the plight of Padre Pio, Pierre excitedly told me of a mystical encounter he had with Padre Pio as a young man. A letter from his father to him at his boarding school in Italy instructed him to go to San Giovanni Rotondo to ask for the blessing of the famous stigmatist, Padre Pio.

When 16-year-old Pierre got there, a friar answering the door told him this was impossible. He then gave Pierre a blessed holy card and ushered him toward the door. Just then, while inside the cavernous Capuchin Friary, an old man with bandaged hands came slowly down a flight of stairs and walked directly to the surprised teenager. Padre Pio held Pierre there firmly with his bandaged hands while he spoke aloud a blessing and prayer. Pierre was stunned, and never forgot it.

Sixty years later, Pierre had a dream that this blessing from Padre Pio was for us, and he wanted to pass it on. He insisted that he must be permitted to become Pornchai Moontri’s Godfather when Pornchai was received into the Church on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010.

Pierre left this life in 2020 just as Pornchai was awaiting his deportation to Thailand, his emergence from prison and the start of a new life. To this day, we both hold Padre Pio in awe as a mentor and friend. He gave us spiritual hope when there was none in sight. His advice is profoundly simple and characteristically blunt:

“Pray, hope, and don’t worry.”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading. Please share this post so it may come before someone who needs it. And please Subscribe if you have not done so already. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls.

I Am a Mystery to Myself! The Last Days of Padre Pio

Stones for Pope Benedict and the Rusty Wheels of Justice

Following revelations about possible deliverance after 28 years of wrongful imprisonment, hope is hard to come by, but it was not so for Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

Following revelations about possible deliverance after 28 years of wrongful imprisonment, hope is hard to come by, but it was not so for Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

February 9, 2022

“This prisoner of the State remains, against all probability, staunch in spirit, strong in the faith that the wheels of justice turn, however slowly.”

— Dorothy Rabinowitz, “The Trials of Father MacRae,” The Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2013

When this blog was but a year old back in 2010, my friend and prison roommate, Pornchai Moontri, was received into the Catholic faith. He was 36 years old and it was his 18th year in prison. Everyone who knew him, except me, thought his conversion seemed quite impossible. Pornchai does not have an evil bone in his body, but his traumatic life had a profound effect on his outlook on life and his capacity for hope. There is simply no point in embracing faith without cultivating hope. The two go hand in hand. We cannot have one without the other.

To sow the seeds of hope in Pornchai, I had to first reawaken hope from its long dormant state in my own life as a prisoner. I am not entirely sure that I have completed that task. It seems a work in progress, but Pornchai’s last words to me as he walked through the prison gates toward freedom on September 8, 2020 were, “Thank you for giving me hope.” I wrote of that day in “Padre Pio Witness for the Defense of Wounded Souls.”

A decade earlier, back in April of 2010, Pornchai entered into Communion with the Catholic Church on Divine Mercy Sunday. On the night before, he asked me a haunting question. It was what I call one of his “upside down” questions. As he pondered what was to come, his head popped down from his upper bunk so he appeared upside down as he asked it. “Is it okay for us to hope for a happy ending when Saint Maximilian didn’t have one?” Pornchai had a knack for knocking me off the rails with questions like that.

Before responding, I had to do some pondering of my own. Our Patron Saint lost his earthly life at age 41 in a Nazi concentration camp starvation bunker. His death was followed by his rapid incineration. All that Maximilian Kolbe was in his earthly existence went up in smoke and ash to drift in the skies above Auschwitz, the most hopeless place in modern human history.

Retroactive Guilt and Shame

What I am about to write may seem horribly unpopular with those harboring an agenda against Catholic priests, but popularity has never been an important goal for me. In recent weeks, the news media has trumpeted a charge launched by a commission empowered by some Catholic officials in Germany. The commission’s much-hyped conclusion was that Pope Benedict was negligent when he did not remove four priests quickly enough after suspicions of abuse forty-one years ago in 1981. Some of my friends have cautioned me to stay out of this. Perhaps I should listen.

But I won’t. At what point do we cease judging men of the past for not living up to the ideals and politically correct sensitivities of the present? Merely asking that question puts me in the crosshairs of our victim culture, but it also forces me to ask another. Go back just another forty-one years and you will find yourself amid the hopelessness of 1941 as the children of Yahweh suffered unspeakable crimes in Germany and Poland. Where do we draw the line of historic condemnation? Should the German Church stop with Joseph Ratzinger in 1981?

The condemnation of Pope Benedict called for by some media and German officials today should be seen through the lens of history. It is a part of our hope as Catholics and as human beings that neither Pope Benedict nor the German people would act today as they did — or allowed to be done — forty or eighty years ago. The real target of such pointless inquiry and blame was not Pope Benedict, but rather hope itself.

I think we have to be clear in our response which should include something about the splinters in our eyes and the planks in the eyes of those pointing misplaced fingers of blame. Perhaps the moral authority that chastises Pope Benedict today in Germany doth protesteth too much. A new book by historian Harald Jähner, Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich, 1945-1955 marshals a plethora of facts and critical skills of historical writing to portray the postwar “country’s stubborn inclination toward willful delusion.”

Thank you for indulging my brief tirade. Catholic League President Bill Donohue also came to the defense of Pope Benedict by shedding some light of historical context on the matter.

Hope Is Its Own Fulfillment

But back to Father Maximilian Kolbe. On the day of Pornchai’s Baptism, I responded to his question. I told him, “YOU are Maximilian’s happy ending!” Eighty-one years after his martyrdom at Auschwitz, the world honors him while the names of those who destroyed him have simply faded into oblivion. No one honors them. No one remembers them. God remembers. Their footprint on the Earth left only sorrow.

St. Maximilian Kolbe is the reason why I was compelled to set aside my own quest for freedom — which seemed utterly hopeless the last time I looked — in order to do what Maximilian did: to save another.

In all the anguish of the last two years as deliverance and freedom slowly came to Pornchai Moontri, the clouds of the past that overshadowed him began to lift. My prayer had been constant, and of a consistently singular nature: “I ask for freedom for Pornchai; I ask for nothing for myself.”

I am no saint, but that is what St. Maximilian did, and it seemed to be my only path. But since then that 2013 quote atop this post from The Wall Street Journal's Dorothy Rabinowitz has once again become my reality. As you know if you have been reading these pages in recent weeks, a frenzy of action and high anxiety has surrounded the recent release of the New Hampshire ‘Laurie List,’ known more formally as the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule. If you somehow missed the earthquake that struck from Beyond These Stone Walls in January, I wrote about it in Predator Police: The New Hampshire ‘Laurie List’ Bombshell.

I am most grateful to readers for making the extra effort to share that post. It was emailed by Dr. Bill Donohue to the entire membership of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. It indeed came as a bombshell to me and to many. Just as the frenzy began to subside, Ryan MacDonald stirred it up again in his brilliant analysis with a very pointed title: “Police Misconduct: A Crusader Cop Destroys a Catholic Priest.”

I am not entirely sure that “destroys” is the right term to use, but I understand where he is coming from. To survive twenty-eight years of wrongful imprisonment means relegating a lot of one’s sense of self to the ash heap of someone else’s oppression. Many of those who spend decades in prison for crimes they did not commit lose their minds. Many also lose their faith, and along with it, all hope.

I have to remind myself multiple times a day that nothing is a sure thing anymore — neither prison nor freedom. I keep asking myself how much I dare to trust hope again. To quote the late Baseball Hall of Famer, Yogi Berra, this all feels “like deja vu all over again.”

Deja vu is a French term which literally means “to have seen before.” It is the strange sensation of having been somewhere before, or having previously experienced a current situation even though you know you have not. It is a phenomenon of neuropsychology that I have experienced all my life. About 15 percent of the population has that experience on occasion.

A possible explanation of deja vu is that aspects of the current situation act as retrieval cues in the psyche that unconsciously evoke an earlier experience long since receded from conscious memory, but resulting in an eerie sense of the familiar. It feels more strange than troublesome. I have a lifelong condition called Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE) which makes me prone to the experience of deja vu, but no one knows exactly why.

When Disappointments of the Past Haunt the Present

This time, my deja vu is connected to real events of the past, and the origin of my caution about current hope is found there. If you have read an important post of mine entitled “Grand Jury, St. Paul’s School, and the Diocese of Manchester,” then you may recall this story. In 2003 and 2004, the New Hampshire Attorney General conducted an intense one-sided investigation of my diocese, the Diocese of Manchester. When it was over, the former Bishop of Manchester signed a blanket release disposing of the privacy rights of priests of his diocese.

In 2021, when I wrote the above post, New Hampshire Judge Richard B. McNamara ruled that the 2003 public release of one-sided documents should have been barred under New Hampshire law because it was an abuse of the grand jury system and it denied basic rights of due process to those involved.

At the time this all happened in 2003, a Tennessee lawyer and law firm cited in a press statement that what happened in this diocese was unconstitutional. I contacted the lawyer who subsequently took a strong interest in my own case. He flew to New Hampshire twice to visit me in prison. I sent him a vast amount of documentation which he found most compelling. After many months of cultivated hope, he sent me a letter indicating that he would soon send a Memorandum of Understanding that I was to sign laying out the parameters under which he would represent me pro bono because I have not had an income for decades.

I waited. I waited a long time, but the Memorandum never came. Without explanation or communication of any kind, the lawyer and the hope he brought simply faded away. Letter after letter remained unanswered. It was inexplicable. It was at this same time that Dorothy Rabinowitz and The Wall Street Journal published a two-part exposé, A Priest’s Story, on the perversion of justice that became apparent in their independent review of this matter. Those articles were actually published a few years after they were first planned. This was because the reams of supporting documents requested and collected by the newspaper were destroyed in the collateral damage of the terrorist attacks in New York of September 11, 2001.

Then in 2012, new lawyers filed an extensive case for Habeas Corpus review of my trial and imprisonment. It is still available at the National Center for Reason and Justice which mercifully still advocates for justice for me. However that effort failed when both State and Federal judges declined to allow any hearing that would give new witnesses a chance to testify under oath.

Now, in 2022 in light of this new ray of hope, some of the people involved in Beyond These Stone Walls have expressed frustration with my caution and apparent pessimism. I have not been as enthused as they have been over the hope arising from the current situation. Hope for me has been like investing in the stock market. Having lost everything twice, I am hesitant to wade too far into the waters of hope again.

I know only too well, however, that hope at times such as these is like that which both Pornchai Moontri and I once found in our Patron Saint. I wrote about it in “Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance.”

So in spite of myself, I am now aboard this new train of hope and must go where it takes me. That, for now, is the best that I can do. My prayer has not changed. I ask for nothing for myself, but I will take whatever comes.

I thank you, as I have in the past, for your support and prayers and for being here with me again at this turning of the tide. I will keep you posted, but it won’t be quick. Real hope never is.

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae:

Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Please visit our newest addition to the BTSW menu: The Wall Street Journal. You may also wish to visit these relevant posts cited herein:

Predator Police: The New Hampshire ‘Laurie List’ Bombshell

Police Misconduct: A Crusader Cop Destroys a Catholic Priest

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

A Parable of Divine Mercy: Pornchai Moontri has a first birthday in freedom on September 10. One third of his life passed in a prison cell with a Catholic priest.

A Parable of Divine Mercy: Pornchai Moontri had a first birthday in freedom on September 10. One third of his life passed in a prison cell with a Catholic priest.

September 8, 2021

Jesus taught in parables, a word which comes from the Greek, paraballein, which means to “draw a comparison.” Jesus turned His most essential truths into simple but profound parables that could be easily pondered, remembered, and retold. The genre was not unique to Jesus. There are several parables that appear in our Old Testament. I wrote of one some time ago — though now I cannot recall which post it was — about the Prophet Jonah.

The Book of Jonah is one of a collection of twelve prophetic books known in the Hebrew Scriptures as the Minor Prophets. The Book of Jonah tells of events — some historical and some in parable form — in the life of an 8th-century BC prophet named Jonah. At the heart of the story, Jonah was commanded by God to go to Nineveh to convert the city from its wickedness. Nineveh was an ancient city on the Tigris River in what is now northern Iraq near the modern city of Mosul. It was the capital of the Assyrian Empire from 705-612 BC.

Jonah rebelled against the command of God and went in the opposite direction, boarding a ship to continue his flight from “the Presence of the Lord.” When a storm arose and the ship was imperiled, the mariners blamed Jonah and cast him into a raging sea. He was swallowed by “a great fish” (1:17), spent three days and nights in its belly, and then the Lord spoke to the fish and Jonah “was spewed out upon dry land” ( 2: 10) . ( I could add, as a possible aside, that the great fish might later have been sold at market, but there was no longer any prophet in it!)

Then God, undaunted by his rebellion, again commanded Jonah to go to Nineveh. Jonah finally went, did his best, the people repented, and God saved them from destruction. Many biblical scholars regard this part of the Book of Jonah as a parable. Jesus Himself referred to the Jonah story as a presage, a type of parable account pointing to His own death and Resurrection:

“Some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, 'Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.' But he answered them, 'An evil and adulterous generation asks for a sign, but no sign will be given except the sign of the Prophet Jonah. For just as Jonah was three days in the belly of the giant fish so for three days and three nights, the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth.”

— Matthew 12:38-40

What I take away from the parable part of the story of Jonah is that there is no point fleeing from “the Presence of the Lord.” God is not a puppeteer dangling and directing us from strings. Rather, the threads of our lives are intertwined with the threads of other lives in ways mysterious and profound. I have written several times of what I call “The Great Tapestry of God.” Within that tapestry — which in this life we see only from our place among its tangled threads — God connects people in salvific ways, and asks for our cooperation with these threads of connection.

The Parable of the Priest

I was slow to awaken to this. For too many days and nights in wrongful imprisonment, I pled my case to the Lord and asked Him to send someone to deliver me from this present darkness. It took a long time for me to see that perhaps I have been looking at this unjust imprisonment from the wrong perspective. I have railed against the fact that I am powerless to change it. I can only change myself. I know the meaning of the Cross of Christ, but I was spiritually blind to my own. Ironically, in popular writing, prison is sometimes referred to as “the belly of the beast.”

After a dozen years of railing against God in prison, I slowly came to the possible realization that no one was sent to help me because maybe I am the one being sent. My first nudge in this direction came upon reading one of the most mysterious passages in all of Sacred Scripture. It arose when I pondered what exactly happened to Jesus between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, the three days He refers to in the Sign of Jonah parable in the Gospel of Matthew above. A cryptic hint is found in the First Letter of Peter:

“For it is better to suffer for good, if suffering should be God's will, than to suffer for evil. For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the Spirit, in which he also went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison who in former times did not obey.”

— 1 Peter 3:17-20

The second and much stronger hint also came to me in 2006, twelve years after my imprisonment commenced. This may be a familiar story to long time readers, but it is essential to this parable. I was visited in prison by a priest who learned of me from a California priest and canon lawyer whom I had never even met. The visiting priest was Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan who, unknown to me at the time, had been a postulator for the cause of sainthood of St. Maximilian Kolbe whom I barely knew of.

Our visit was brief, but pivotal. Father McCurry asked me what I knew about Saint Maximilian Kolbe. I knew very little. A few days later, I received in the mail a letter from Father McCurry with a holy card (we could receive cards then, but not now). The card depicted Saint Maximilian in his Franciscan habit over which he partially wore the tattered jacket of an Auschwitz prisoner with the number, 16670. I was strangely captivated by the image and taped it to the battered mirror in my cell.

Later that same day, I realized with profound sadness that on the next day — December 23, 2006 — I would be a priest in prison one day longer than I had been a priest in freedom. At the edge of despair, I had the strangest sense that the man in the mirror, St. Maximilian, was there in that cell with me. I learned that he was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1982, the year I was ordained. I spent a lot of time pondering what was in his heart and mind as he spontaneously stepped forward from a line of prisoners and asked permission to take the place of a weeping young man condemned to death by starvation. I wrote of the cell where he spent his last days in “Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance.”

On the very next day after pondering that man in the mirror on Christmas Eve, 2006 — a small but powerful book arrived for me. It was Man’s Search for Meaning, by Auschwitz survivor, Dr. Viktor Frankl, a Jewish medical doctor and psychiatrist who was the sole member of his family to survive the horror of the concentration camps. I devoured the little book several times. It was one of the most meaningful accounts of spiritual survival I had ever read. Its two basic premises were that we have one freedom that can never be taken from us: We have the freedom to choose the person we will be in any set of circumstances.

The other premise was that we will be broken by unending suffering unless we discover meaning in it. I was stunned to see at the end of this Jewish doctor’s book that he and many others attributed, in part, their survival of Auschwitz to Maximilian Kolbe “who selflessly deprived the camp commandant of his power over life and death.”

The Parable of a Prisoner

God did not will the evil through which Maximilian suffered and died, but he drew from it many threads of connection that wove their way into countless lives, and now I was among them. For Viktor Frankl, a Jewish doctor with an unusual familiarity with the Gospel, Maximilian epitomized the words of Jesus, “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

I asked the Lord to show me the meaning of what I had suffered. It was at this very point that Pornchai Moontri showed up in the Concord prison. I have written of our first meeting before, but it bears repeating. I was, by “chance,” late in the prison dining hall one evening. It was very crowded with no seats available as I wandered around with a tray. I was beckoned from across the room by J.J., a young Indonesian man whom I had helped with his looming deportation. “Hey G! Sit here with us. This is my new friend, Ponch. He just got here.”

Pornchai sat in near silence as J.J. and I spoke. I was shifting in my seat as Pornchai’s dagger eyes, and his distrust and rage were aimed in my direction. J.J. told him that I can be trusted. Pornchai clearly had extreme doubts.

Over the next month, Pornchai was moved in and out of heightened security because he was marked as a potential danger to others. Then one day as 2006 gave way to 2007, I saw him dragging a trash bag with his few possessions onto the cell block where I lived. He paused at my cell door and looked in. He stepped toward the battered mirror and saw the image of St. Maximilian Kolbe in his Franciscan habit and Auschwitz jacket and he stared for a time. “Is this you?” he asked.

Within a few months, Pornchai’s roommate moved away and I was asked to move in with him. Less than four years later, to make this long and winding parable short, Pornchai was received into the Catholic faith on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010. Two years after that, on the Solemnity of Christ the King, 2012, we both followed Saint Maximilian Kolbe into Consecration to Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Most readers likely know by now the depth of the wounds Pornchai experienced in life. He was abandoned as a child in Thailand, suffered severe malnutrition, and then, at age eleven, he fell into the hands of a monster. He was taken from his country and the only family he knew, and was brought to the U.S. where he suffered years of unspeakable abuse. He escaped to a life of homelessness, living on the streets as a teenager in what was to him a foreign land. At age 18, he accidentally killed a much larger man during a struggle, and was sent to prison.

Pornchai’s mother, the only other person who knew of the years of abuse he suffered, was murdered on the Island of Guam after being taken there by the man who abused him. In 2018, after I wrote this entire account, that man, Richard Alan Bailey, was brought to justice and convicted of forty felony counts of sexual abuse of Pornchai. After the murder of his mother at that man’s hands, Pornchai gave up on life and spent the next seven years in the torment of solitary confinement in a supermax prison in the State of Maine. From there, he was moved here with me.

Over the ensuing years, as I gradually became aware of the enormity of Pornchai’s suffering, I felt compelled to act in the only manner available to me. I followed Saint Maximilian Kolbe into the Gospel passage that characterized his life in service to his fellow prisoners: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

I asked the Lord, through the Immaculate Heart of Mary, to free Pornchai from his past and the seemingly impenetrable prisons that held him bound. I offered the Lord my life and freedom just as Maximilian did on that August day of 1941. Then I witnessed the doors of Divine Mercy open to us.

This blog began just then. In the time he spent with me, Pornchai graduated from high school with honors, earned two additional diplomas in guidance and psychology, enrolled in theology courses at Catholic Distance University, and became an effective mentor for younger prisoners in a Fast Track program. He tutored young prisoners in mathematics as they pursued high school equivalency, and, as I have written above, he had a celebrated conversion to the Catholic faith, a story captured by Felix Carroll in his famous book, Loved, Lost, Found.

Pornchai became a master craftsman in woodworking, and taught his skill to other prisoners. One of his model ships is on display in a maritime museum in Belgium. His conversion story spread across the globe. After taking part in a number of Catholic retreat programs sponsored by Father Michael Gaitley and the Marians of the Immaculate Conception, Pornchai was honored as a Marian Missionary of Divine Mercy. So was I, but only because I was standing next to him.

One of the most beautiful pieces of writing that has graced this blog was not written by me, nor was it written for me. It was written for you. It was a post by Canadian writer Michael Brandon, a man I have never met, a man who silently followed the path of this parable for all these years. His presentation is brief, but unforgettable, and I will leave you with it. It is, “The Parable of the Prisoner.”

+ + +

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance

Book: Man’s Search for Meaning

Book: Loved, Lost, Found

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: On September 10, Pornchai will mark his 48th birthday. It is his first birthday in freedom. In 2020 on that date he was just beginning a grueling five months in ICE detention awaiting deportation. For the previous 29 years he was in prison. For the four years before that he was a homeless teenager having fled from a living nightmare.

I asked him what he would like for his birthday, and this was his response:

“I have never seen the ocean. I would like to go to the Gulf of Thailand and visit my cousin who was eight years old when I was eleven and last saw him. He is now an officer in the Thai Navy.”

Please visit our “SPECIAL EVENTS” page, and our BTSW Library category for posts about Pornchai.

A House Divided: Cancel Culture and the Latin Mass

In Traditionis Custodes restricting the Traditional Latin Mass, Pope Francis insists that his goal is ecclesial communion. Then he dropped a bombshell of division.

In Traditionis Custodes restricting the Traditional Latin Mass, Pope Francis insists that his goal is ecclesial communion. Then he dropped a bombshell of division.

In the above composite photo Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and Pope Francis offer Mass Ad Orientem in the Sistine Chapel.

August 11, 2021

The Year of Our Lord 2003 seemed a lot more like a year of Our Lord’s Calvary. It was a most painful year for me personally and for many Catholics. Starting in Boston with a rapid ripple effect across the land, diocese after diocese faced relentless Catholic scandal over the horror of Catholic priests accused of sexual abuse. A spotlight was cast upon the Catholic Church to the delight of the news media, but the subject needed a flood light. There was little justice in the moral panic to follow. This is a story I wrote about in a recent post, “A Sex Abuse Cover-Up in Boston Haunts the White House.”

Just beyond the glare of The Boston Globe spotlight, there was another event that had an even more profound impact on another church community in 2003. It took place just north of Boston in New Hampshire and from there it, too, rippled across the land, and many lands. Its most distinctive feature was its contrast to the Catholic story. While Catholic priests were judged and condemned in the media, one Episcopal clergyman in New Hampshire became a celebrity of pop culture.

In 2003, The Reverend V. Gene Robinson became the first openly gay Episcopalian priest to be nominated to become a bishop. The announcement had the immediate effect of alienating conservative members of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Born Vicky Gene Robinson in 1947, the nominee had been married, raised a family, divorced, and was in a conjugal same-sex relationship at the time of his nomination. For many, this seemed more of a politically correct statement than a serious nomination. If The Reverend Robinson had been divorced and living with another woman who was not his wife, this nomination would have gone nowhere.

Bishop Robinson’s nomination was confirmed by the Episcopal church of New Hampshire to equal parts applause and dismay. Then the cascade of damage was set in motion. With the support of the Nigerian Anglican church, many American conservative Episcopalians broke from the Worldwide Anglican Communion to form the Anglican Church in North America. The Anglican bishops of Uganda announced that they too broke from communion with the Episcopal church. This spread among conservative Anglican bishops across Africa and other parts of the world.

Having torn the Worldwide Anglican Communion asunder, Bishop Robinson announced his retirement seven years later in 2010. At some point he checked into drug rehab, and then used his voice as a retired bishop to promote same-sex marriage before the New Hampshire Legislature. He and his partner were among the first to “marry” under the new law he helped to pass. Then he announced his divorce to a news media that kept it very low key.

Among the protests came a multitude of petitions to Pope Benedict XVI who, in 2009, promulgated the Motu Proprio, Anglianorum Coetibus accepting into the Roman Rite entire Anglican parishes desiring to “cross the Tiber” to join the Roman Church. The first was a parish that became part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Galveston-Houston, Texas in 2009.

We Are on a Road to Calvary Not Schism

The reactions that resulted in a breakup of the Worldwide Anglican Communion could not happen in the Catholic Church. Canon Law does not allow for the decisions to leave promoted by the Anglican bishops of Africa and other conservative communities. Only the Holy See can declare that a schism exists in a region or diocese. Popes have gone to great lengths to avoid schism. Pope Benedict XVI lifted the excommunication of Bishops in the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX) to heal a longstanding rift with traditionalists. In 2007, Pope Benedict further mended that rift with his Motu Proprio, Summorum Pontificum, which removed obstacles to the Traditional Latin Mass.

Now Pope Francis has reopened those wounds anew with Traditionis Custodes, his Motu Proprio: announced on July 16, 2021 which contradicts and revokes the permissions granted by Pope Benedict. I wrote of this last week in these pages in “Pope Francis Suppresses the Prayers of the Faithful.”

I used that title because in many ways my experience of the vast majority of those who seek out the Latin Mass are among the most faithful. In a published Letter to the Editor of The Wall Street Journal on July 30, 2021, writer Ray Martin of Ridgefield, Connecticut described what has become a lax and often disrespectful atmosphere in too many parishes. This is an impression that I hear about frequently from readers:

“I do not regularly attend a Latin Mass but I do remember it from childhood ... Nowadays, fewer Catholics attend Mass regularly, they tend to come late and leave early, and it is not unusual to see T-shirts, short-shorts and flip flops. Everyone presents at the altar for Communion. One study found that around one in three Catholics believes in the True Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. I would guess that more than 90-percent of Latin Mass attendees do.”

My experience of the many Catholics I hear from who seek out the Latin Mass either weekly or even just on occasion is that they are our modern day Essenes. I wrote of the Essenes and their role in preserving the faith of both Israel and the early Jewish Christians in “Qumran: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Coming Apocalypse.” When Pope Benedict XVI opened the Church door to those requesting the Tridentine Latin Mass, many thought it would draw only senior citizens and some “far-right cranks,” as one writer put it back then. That has been far from true. Pope Francis expressed a concern that many who take part in the Latin Mass deny the validity of the Novus Ordo, the form of the Mass promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1970. This also is far from true. I hear from many Latin Mass attendees who also take part in the Novus Ordo Mass. All they ask for is a sense of the sacred, and a communal acknowledgment that Jesus is truly present in the Eucharist. Their appreciation of the Novus Ordo has been strengthened by the Latin Mass.

Writing for The Wall Street Journal, Matthew Walther, editor of The Lamp magazine, penned an eye-opening op-ed one week after Pope Francis announced new, severe and immediate restrictions on the Latin Mass. Entitled, “Pope, Francis, the Latin Mass, and My Family” (July 23, 2021), Mr. Lamb described the reaction of those in his Catholic community of faith:

“We are loyal children of the Church on the receiving end of a harsh punishment. Pope Francis ... seemed to suggest that things had gone too far and were threatening to undo the liturgical reforms of the 1960s. The gradual displacement of the new rite, which emerged after Vatican II, was in fact the half-articulated ambition of many traditionalists. Until recently many had looked forward to a future in which the ‘extraordinary form’ of the Mass, as Benedict referred to it, was set to become rather ordinary.”

Perhaps that is the point. The solemnity, majesty, and sacredness of the sacrifice taking place is just that — extraordinary. I want to contrast that with an experience I had as a newly ordained priest in one New Hampshire parish whose pastor made a weekly show of rushing through Sunday Mass at warp speed. After his hasty final blessing he would look at his watch and declare, “Twenty-two minutes, and I didn’t miss a thing!”

Standing with Peter v. Standing Our Ground

In some ways, Pope Francis has been unpredictable for so-called progressive Catholics as well. After playing down the issue of homosexuality with oft-quoted remarks like, “Who am I to judge?”, he disappointed many in liberal Catholic enclaves like Germany when he refused to allow blessings of same-sex unions. He dismissed the proposition while shocking liberal German priests with the definitive statement, “God cannot bless sin.” In an open letter to German Catholics in 2019, he cautioned them against “multiplying and nurturing the evils the Church wants to overcome.” He also gave a definitive “no” on the topic of ordination of women.

With all the open, and often flagrant, dissent from Church teaching and discipline in Germany and other parts of Europe, why would Francis choose to label traditional Catholics who appreciate the Latin Mass as “divisive?” I do not have answers.

But I do have more questions and a few suspicions. As I pointed out in these pages a week ago, there is an immense and growing contrast between the state of the Catholic Church in Germany and other areas in Europe, and that of the Church in Africa. The former has been in a state of stagnation for decades, and is now deeply involved in the embrace of what has come to be called, “Cancel Culture.” In its Catholic manifestation, I can only describe this as the setting aside of the “sensus fidei,” the sense of the faith as it has been expressed across two millennia, in favor of populist social trends of just the first two decades of the 21st Century.

With that understanding, “Cancel Culture” has become a modern plague on humanity that is far more destructive than any viral pandemic. If we do not understand history, and learn from it, we are doomed to repeat its most destructive patterns. Joining this secularized culture by placing God on the shelf while morphing Roman Catholicism into a mirror image of the flailing American Episcopal church is perilous.

The rapid growth of the Traditional Latin Mass since Pope Benedict XVI re-opened that door may well be the work of the Holy Spirit. Pope Francis knows well that the entire Church — and not just the bishops with whom he consulted — comprises the “sensus fidelium,” the action of the Holy Spirit in the hearts and minds and souls of the faithful from the Sacrifice at Calvary to the present day. The faithful witness of those who embrace the Traditional Latin Mass may prove to be a gift to the Church.

But the faithful must not stand against Peter to achieve that end. We are a Church built upon the blood of martyrs, and faithful witness may now require paying the cost of discipleship. Sometimes in the Church’s story of faith, white martyrdom has not only been for the Church. Sometimes it has been from the Church. Padre Pio knew this. So did Cardinal George Pell. So do I.

I have been most struck by the two volumes of Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal. He frequently repeated his longing for Mass and the Eucharist in a place where he was barred from them. I recall reading from Father Walter Ciszek’s book, With God In Russia, that he sat on the edge of his bunk in a Siberian labor camp and would mouth from memory the words of the Roman Canon of the Mass.

My experience of Mass as a prisoner is reduced to the contents of a small plastic box. On Sunday nights at 11:00 PM, after the last prisoner count of the day, I take that box from a shelf and place it at the foot of my prison bunk. It serves as both a container and an altar. It has a Corporal that I spread over its surface. I attach a small battery powered book light to the wall just above it, and begin my preparation for Mass. The Mass is always “Ad Orientem,” toward the East, not by any design of my own, but because the cell window faces in that direction.

I have no sacred vessels. I have a coffee cup purchased years ago but never used for any other purpose. I have a weekly supply of a host placed on a clean linen purificator, and a one-quarter ounce of unfermented wine with no additives approved for liturgical use by Catholic priests serving in a war zone. I have a small wooden crucifix on a stand on a shelf just above where my Mass is offered.

There was a time when I did not have even these. For many years in prison, I had no access at all to the Mass. So I look upon this present drama unfolding now in our Church, and see it as madness that is hopefully brief. If you have appreciated the Traditional Latin Mass, you must not leave. The Church needs you. We need you to remind us of a lesson that I have long since learned harshly, and can now never forget.

What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please share this post. And please visit our Special Events page. It contains a story that is dear to my heart.

You may also like these relevant posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Pope Francis Suppresses the Prayers of the Faithful

The feast of Saint Maximilian Kolbe, our patron saint, is August 14. The above photo is his prison cell.

It Is the Duty of a Priest to Never Lose Sight of Heaven

Marking 39 years of priesthood, 27 of them unjustly in prison, this priest guides readers to higher truths. For those who suffer in life, eternal life matters more.

Marking 40 years of priesthood, 28 of them unjustly in prison, this priest guides readers to a higher truth. For those suffering in life, eternal life matters more.

“When suffering is far away, we feel that we are ready for everything. Now that we have occasion to suffer, we must take advantage of it to save souls.”

I am indebted to my friend, Father Stuart MacDonald, JCL, for his remarkable and timely guest post, “Bishops, Priests, and Weapons of Mass Destruction.” In it, he concluded that some of our bishops have acted in regard to their priests by caving into the cancel culture mob even before it was called that. “The mob can be a frightening place when we have lost sight of heaven,” he boldly wrote. I was struck by this important insight which lends itself to my title for this post: It is the duty of a priest to never lose sight of heaven.

In the weeks before I mark forty years of priesthood, I have heard from no less than three good priests who have been summarily removed from ministry without a defense. Like many others, they are banished into exile following 30-year-old claims for which there exists no credible evidence beyond the accusations themselves and demands for money.

This sad reality, imposed by our bishops in a panicked response to the Catholic abuse crisis, has been the backdrop of nearly half of my life as a priest. As Father Stuart mentioned in his post, I wrote of this a decade ago in regard to the demise of the celebrated public ministry of Father John Corapi at EWTN. Given the resurgence of priests falsely accused, I decided to update and republish that post on social media. It is “Goodbye, Good Priest! Fr. John Corapi’s Kafkaesque Catch-22.”

The point of it was not Father Corapi himself, but rather the matters of due process and fundamental justice and fairness that have suffered in regard to the treatment of accused priests. In republishing it, I was struck by how little has changed in this regard since I first wrote of Father Corapi a decade earlier.

My article presents no new information on the priesthood of Father Corapi, but lest our spiritual leaders think that interest in this story among Catholics has diminished, within 24 hours of publishing, that post was visited by over 6,500 readers and shared on social media 3,700 times. (Note: We now give it a permanent home in the “Catholic Priesthood” Category at the BTSW Library.)

The only priests who land in the news these days are those accused of sexual or financial wrongdoing and those who make their disobedience to Church authority in matters of faith and morals a media event. In regard to the latter, several priests and bishops in Germany have openly defied Pope Francis and his decision to bar priests from blessing same-sex unions.

Blessing the individuals involved would not be an issue, but, as Pope Francis put it, “The Church cannot bless sin.” The open defiance of this among some German priests brought them 15 minutes of fame in our cancel culture climate in recent weeks, but it does nothing to bring us any closer to heaven.

Appearing on The World Over with Raymond Arroyo recently, Catholic theologian and author, George Weigel, addressed the German situation plainly:

“These bishops think that they know more about marriage than Jesus, that they know more about worthiness for the Eucharist than Saint Paul. This is apostasy, and it is time to call it what it really is.”

The Setting for My Priesthood

In every age, people tend to see the struggles of their current time as the worst of times. My priesthood ordination took place on June 5, 1982. It was the only ordination in the Diocese of Manchester, New Hampshire that year. President Ronald Reagan was in the second year of his first term in office. The U.S. economy was suffering its most severe decline since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Unemployment was at its highest level in decades and the housing industry was on the verge of collapse.

Just over a year earlier, on May 13, 1981, Pope John Paul II was shot four times at close range as he entered Saint Peter’s Square to mark the 64th anniversary of the first appearance of Our Lady of Fatima in Portugal. John Paul was severely wounded and so was the spirit of the global Catholic Church. He recovered, though a lesser man might not have.

One year later, three weeks before my ordination, Pope John Paul made a thanksgiving visit to Fatima on May 12, 1982. It was the day before the anniversary of both the Visions of Fatima and the attempt on his life. As the Pope walked toward the altar of the Fatima shrine, a man in clerical garb lunged at him with a bayonet, coming within inches of killing John Paul before being subdued by security guards.

The assailant was Juan Fernandez y Krohn, then age 32, a priest ordained by the suspended traditionalist French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. Fernandez was subsequently expelled from Lefebvre's movement. As he lunged at the Pope with his bayonet, he shouted in denouncement of the Second Vatican Council while accusing Pope John Paul of collaborating with the dark forces behind the spread of Communism.

That latter accusation was highly ironic. Over the next decade, Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II collaborated to become the two major forces behind the collapse of the Soviet Union and European Communism that had held the Western World in the grip of Cold War since the end of World War II.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall was torn down by a crowd of citizens from both East and West as soldiers watched in silence. On Christmas Day, 1991, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev announced his resignation in a television address. The next day, the Soviet parliament passed its final resolution ratifying the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Within a week, all residual functions of the Soviet Communist state ceased. The USSR was no more, thanks to the strength and fidelity of a Pope and a President.

The footprints of Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul on modern human history are immense. This and the chaos of the world at that time formed the backdrop against which I became a priest in 1982. I wrote of this in “Priesthood: The Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times.”

The sins of the times were many. On the world stage, Pope John Paul courageously confronted the Marxist “cancel culture” movement of his time. His bold witness to the world and his fidelity are highlighted in a new and important book by George Weigel entitled Not Forgotten.

In contrast, much of the current Catholic ecclesial leadership seems bogged down in demonstrations of tolerance for dissent and the rise of socialism and Marxist ideology that again springs up anew as “cancel culture.” Some bishops cannot even decide whether open promotion of abortion should bar its adherents who are nominally Catholic from presenting themselves for the Eucharist.

Ironically, recent polls have suggested that 66-percent of American Catholics are uncertain whether they still even believe in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. It is that exact same percentage who also believe that President Biden should be admitted to the Eucharist without question despite his open promotion of abortion as a civil right. Our Catholic crisis is not just one of fidelity. It is a crisis of identity. But as has been famously asked by another well-known priest, “Who am I to judge?”

Witnessed in a Prison Journal

Now here I stand, 39 years into my priesthood on the peripheries with 27 of those years in wrongful imprisonment for abuse claims that never took place. I could have left prison 26 years ago had the truth meant nothing to me. I have been reading the far better known story of another falsely accused priest in the Prison Journal of George Cardinal Pell published by Ignatius Press.

I find in it much solace and peace. I am strengthened in my priesthood by the great effort of Cardinal Pell to maintain his identity as a priest even in prison. I know from long experience - too long - that there is nothing in prison, absolutely nothing that sustains an identity of priesthood. It is so easy and a constant temptation to simply give up. For page after page in the Journal, I find myself thinking, “I felt that very same way,” or “I did these very same things.” Our prisons were similar, although from Cardinal Pell descriptions, Australia’s prisons seem a bit more humane.

Cardinal Pell was in prison for 400 days before his unjust convictions were recognized as such in a unanimous exoneration by Australia’s High Court. On my 39th anniversary of ordination on June 5th this year, I mark 9,750 days in wrongful imprisonment. I do not point this out to contrast my experience with that of Cardinal Pell. His ordeal, like mine, was defined by his first failed appeals after which he had every reason to believe that prison could thus define the rest of his life.

I have no known recourse because, unlike Australia, the United States courts have given greater weight to states’ rights to finality in criminal cases than to innocent defendants’ rights to a case review. When I had new witnesses and evidence, the court not only declined to hear it, but declined to allow any further appeals. We even appealed that, but to no avail.

But a distinction between justice for Cardinal Pell and for me is not the point I want to make. I felt the lacerations to his good name in every step of his Way of the Cross as news media in Australia and globally exploited the charges against him. What a trophy his wrongful conviction was for those who hate the Church!

I felt the scourging he endured as multiple false claimants tried to use his cross for financial gain. I felt his condemnation in the halls of the high priests as cowardly men of the Church denounced him, at worst, or at best stood speechless in the shadows of silence, rarely mentioning his name, and even then only in whispers.

Reading Volume One of Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal has been both consoling and distressing. Consoling in that when all else was stripped away, truth and priesthood, even more than freedom, were still at the heart of this good priest’s identity. The measure of a man is not when all is going well, but when all that is dear and familiar has been stripped away. Cardinal Pell held up well. I like to think I have, too.

I have reserved a copy of Volume Two of the Prison Journal. I am told by those who know that in a few of its pages, Cardinal Pell also wrote about me. That struck me as highly ironic in that I wrote several times about his plight, the last being “From Down Under, the Exoneration of George Cardinal Pell.”

And by “From Down Under,” I do not just mean Australia!

The Last Years of My Priesthood

I expect that I will die in prison. This is not a statement out of despair. No one has taken my faith in Divine Providence and Divine Mercy. There came a time in my imprisonment when I recognized a pattern of grace that began with the insinuation of Saint Maximilian Kolbe into my life as both a priest and a prisoner. This grace has been profound, and staggering in its visibility and power. Our readers — all but the most spiritually blind — have seen it.

After a lifetime of devoting himself as a priest in Consecration to Jesus through Mary, Maximilian coped with his suffering as grace rather than torment. This story culminated, as you know, in his spontaneous decision to surrender his life so that another could live. This act of sacrifice has long been heralded as an exemplar of the words of Jesus, “No greater love has a man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

There came a point in my imprisonment when it was clear that all I tried to do to bring about justice was in vain. So I asked for Divine Mercy and the ability to find grace in this story. A life without grace is far worse than a life without justice. It was at that very point at which my friend, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri, arrived upon my road as a priest. He had been mercilessly beaten down in life, and robbed of all trust and hope.

I could have been the priest who saw him on that road and passed him by like the priest in the Parable of the Samaritan. But I stopped, and when I learned the whole truth of his life, I set my own hope for justice aside. It became clear to me that this was God’s action in my life and a task that He has given only to me. It became clear that Pornchai has a special connection to Christ through the Immaculate Heart of Mary and I was to be his Saint Joseph.

I wrote a post about this healing mission which I contrasted with the Book of Tobit and the mission of Saint Raphael the Archangel to be God’s instrument of healing. I wrote of this in one of my own favorite posts at Beyond These Stone Walls in “Archangel Raphael on the Road with Pornchai Moontri.”

You should not miss that post, and if you do read it, you would do well to ponder for awhile the mysteries of grace on your own life’s path. It was well after writing and posting it that I learned something that stunned me into a better awareness of the irony of grace.

Over the course of time, the Church has devised a Lectionary that reveals all of Sacred Scripture in the readings for the Church’s liturgy spread over a three-year cycle. I discovered only while writing this post for the occasion of my 39th anniversary of priesthood ordination that the First Reading at Mass on that day — Saturday, June 5, 2021 — is the story of the Archangel Raphael sent by God to restore life and sight to Tobit and bring deliverance and healing to two souls — Tobias and Sarah — whose lives and sufferings converged upon Tobit’s at that point in time.

As I mark thirty nine years as a priest in extraordinary circumstances, the weight of imprisonment does not leave me broken. But the irony of grace leaves me hopeful — even now.

Thank you for being a part of my life as a priest. Thank you for being here with me at this turning of the tide.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: We have a most important message for readers. Please visit our “Special Events” page.

+ + +

You may also like these related posts:

From Down Under, the Exoneration of Cardinal George Pell

Priesthood, The Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times